Prophetic Witness and Radical Love: A Conversation with Cornel West

Bearing Witness: In his ongoing column, Karlos K. Hill highlights the efforts of cultural figures doing works of essential good around issues of social justice.

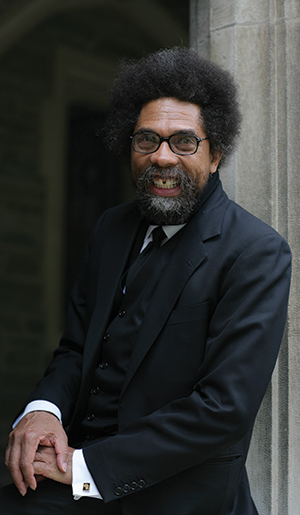

Cornel West, who recently retired from Princeton University as the Class of 1943 University Professor in the Center for African American Studies, visited the University of Oklahoma in August 2023. He was on campus to take part in OU’s Presidential Speaker Series in a point/counterpoint discussion, “Saving America: Conflicting Views in Civil Dialogue,” with his Princeton colleague Robert P. George. Dr. West graciously sat down with me before that conversation to take part in the following exchange for World Literature Today.

Karlos K. Hill: Brother West, I’ve been wanting to tell you that the title of my “Bearing Witness” column comes directly from you. It’s inspired by you.

Cornel West: That’s fascinating.

Hill: Of all my framings, I use bearing witness the most because I’ve heard you talk about it the most: we’ve got to bear witness to injustice. So, this column in World Literature Today is definitely inspired by you. And I’ve made bearing witness, because of you, the cornerstone of how I organize my academic life. It’s not just about teaching, it’s about bearing witness. You know, there’s a profound difference between teaching and bearing witness as you teach. I’ve learned to center that—not only the scholarship but just being in the world—because you centered it as a Black studies scholar, very publicly and unabashedly. This column is really an homage to you. I just want you to know that.

West: That’s beautiful. I appreciate that, brother, I really do. I’m touched by it, man, because we’re all cracked vessels, you know? We are trying to do the best that we can do. Bearing witness is all about trying to be true to the best that’s been poured into us by those who came before, who set such high standards, and we all fall short. Samuel Beckett is right: you try again, fail again, fail better, in that beautiful line in his last prose fiction. And yet, even in failing better, we are able to at least be forces for good, in John Coltrane’s language. That’s really what it’s all about. Whatever the context is—it could be in the classroom, could be in the street, could be in the cell, could be in the suite; it could be in the church, the mosque, the synagogue; it could be on the corner, could be in the nightclub—we all can bear witness.

West: That’s beautiful. I appreciate that, brother, I really do. I’m touched by it, man, because we’re all cracked vessels, you know? We are trying to do the best that we can do. Bearing witness is all about trying to be true to the best that’s been poured into us by those who came before, who set such high standards, and we all fall short. Samuel Beckett is right: you try again, fail again, fail better, in that beautiful line in his last prose fiction. And yet, even in failing better, we are able to at least be forces for good, in John Coltrane’s language. That’s really what it’s all about. Whatever the context is—it could be in the classroom, could be in the street, could be in the cell, could be in the suite; it could be in the church, the mosque, the synagogue; it could be on the corner, could be in the nightclub—we all can bear witness.

Now, of course, it’s also biblical, which is to say it’s about kenosis, you see? It’s about emptying yourself. It’s about resisting the compartmentalization and the specialization that goes with professionalization. When you professionalize, you undergo a certain kind of process and set of protocols where you can become a master and the victim of it simultaneously. Whereas when you bear witness, you got your whole heart, mind, soul, body, memory, history, and you put it into what you’re doing. For you, as teachers, as pedagogical figures, to bear witness means putting your whole self into it, whereas as a professional it’s nice to have your data, your argument, your evidence, and so forth, and to be connected to others who do that. That’s fine. That’s the skill that you’re passing on. But the skill doesn’t necessarily manifest itself in the whole self put into the student. So that you’re not just passing on the skill to the student, but the student is seeing an example of a person of honesty, integrity, and having a calling. And a vocation. You see, there’s no vocation without invocation and provocation. And there’s no calling without recalling.

And we come from a tradition, Black folks, where our anthem is “Lift Every Voice,” so we’re not just echoes. Not “lift every echo,” where you’re just going to be an extension of some little silo, some little group or tribe, or some form of conformity and orthodoxy. No, when you find your voice, you know, you’re like Sarah Vaughan. You’re like Charlie Parker. Something distinctive and unique because you found that voice by listening to voices of the past and bouncing your voice against others. It’s like Dizzy Gillespie. “Where did you find your voice?” “Well, it’s Roy Eldridge and Louis Armstrong. I know I can never reach their level, but I tried to do what I could do.” Thank you, Dizzy. You reached some high level. Of course, Wynton Marsalis, Clifford Brown, Lee Morgan, and others will say the same thing. That’s a great tradition. We can say more about that in terms of where we are now, in terms of the American Empire and what happens when that tradition begins to wane, to get weak and feeble.

But what you’re doing in many ways, Karlos, is being this magnificent conduit and vessel and vehicle for this great tradition. What is distinctive about your corpus, it seems to me, is that you’re one of the few who have been willing to look unflinchingly at the impact of terrorism on Black people’s struggle for structures of feeling and value. You see, most literary critics, they’re very distant from Carl von Clausewitz, the great philosopher of war. Whereas in this country, for Black folk and Indigenous peoples as well, if you don’t understand the role of war and violence and coercion and fraud and lies, then you’re usually part of a deodorized discourse, very sanitized and sterilized. You know what I mean? (in singsong voice) “Let’s talk about discrimination and identity.” Wait, wait, wait—we’re talking about precious human beings who find themselves in the context of a war of violence, and lynching is one of the great manifestations of it. That’s why, even in the debate between W. E. B. Du Bois and Booker T. Washington, without Ida B. Wells, it’s a sanitized discourse. Because Ida said, “Wait a minute. The major force, in the condition of this precious people, is of violence coming at them so intensely to keep them so scared and intimidated and afraid.” That’s the very way in which you try to circumscribe the possibilities of Black imagination, Black feeling, Black joy, Black freedom, and so forth. So, in your work, from the very beginning, brother, you’ve been consistent, I’m telling you.

Hill: It’s because of this, Brother West. I really want to focus back because of your consistent voice about bearing witness to the struggles of poor people. One of my favorite phrases you say is “the least of these.” Bearing witness to the least of these. For me, historically speaking, the least of these have been victims of racial terror. We know Emmett Till’s name, but we don’t know hundreds, if not thousands, of Black people’s names. We’ve known his name for decades, but he still hasn’t got justice. All the other Black people, we can only give them a measure of symbolic justice by, to a certain degree, saying their name, remembering them as something more than the lynching victims that they were reported to have been in death. That has galvanized me and given me something really clear to focus on.

What I say to people now, inspired by you—and I say this everywhere I go—I bear witness to victims, survivors, and descendants of a four-hundred-year assault on Black people and Black bodies. For four hundred years. And I say that everywhere to keep me grounded, everywhere I go, no matter if I’m talking about Brother Till, if I’m talking about Tulsa, if I’m talking about Clara Luper, no matter what, I’m always going to start with saying that. So that I remember, whatever I say needs to be in the interests of those voices of justice. And that has allowed me to be consistent, that ritual. Before I speak to my students, the first day of class, I say, “I bear witness.”

West: I think that, especially in regard to literature and world literature—whatever adjective one wants to use about this being global, cosmopolitan, international, worldly, in Edward Said’s sense, of world literature in the broader sense—going back to C. M. Wieland and Goethe, all the way through the great Madame de Staël, Herder, and others. I was just rereading the magisterial text by David Damrosch, Comparing the Literatures, beginning with Harry Levin and ending with the perturbed souls, so the tradition is not enough. He’s absolutely right.

But when it comes to my own tradition, it’s really music that sits at the center. See, the problem of texts is that they are still so preoccupied with words and language. Do you remember that wonderful moment in Toni Morrison, when the sisters come together and sing and try to release Beloved? And she says, “We got to create a sound that breaks the back of words.” You see, that’s the starting point for Black people. And if you want to hook it up with the Western tradition, it’s Giambattista Vico. Vico begins with wisdom, begins with the muse. That’s why he begins with Homer. He demystifies Homer into the folk songs of everyday Greeks, not the isolated individual. That’s his response to Plato’s Republic and traditional choral poetry and philosophy in book 10 of The Republic. How do you create forms of paideia or education in the deep sense—not schooling in the modern, impoverished sense—but in the deep sense of soul craft, a soul-shaper of people? And it begins with sound, begins with music, you see.

So, the Black musical tradition—which I think is the greatest tradition of the twentieth century in terms of artistic creativity, spiritual fortitude, and moral courage—it doesn’t begin where Du Bois begins, which is with “a problem.” It begins with catastrophe. And to reduce the catastrophic to the problematic is already to deodorize it. One of the reasons your corpus stands out, why I love it, is that there’s never been a race problem in America. There’ve been catastrophes visited upon Indigenous people, visited upon race people. And if we begin with the musicians, they don’t begin with the race problem. “Strange Fruit” is not a problem; it’s a catastrophe. And the question is, How do you ensure catastrophe doesn’t have the last word? That’s where resistance, that’s where remembrance, that’s where resilience, that’s where reference, something bigger than your ego, something bigger than the body that the Klan has just hung on the tree. What’s going to emanate from that body? Memories of those little kids looking at it, right? What’s going to emanate resilience when they come home? What kinds of stories are going to sustain the soul in the face of the lynching, the terrorism, the traumatizing, the hatred, and so forth?

“Strange Fruit” is not a problem; it’s a catastrophe.

Traditionally—and this is true not just for Black folks but for the species—it’s been music. George Steiner, one of the great comparative literary critics, used to say that the greatest question for him—and he got it from Claude Lévi-Strauss—is the invention of melody. How do we account for the invention of melody? And it usually has something to do with wrestling with overwhelming pain, hurt, wounds, bruises, scars. And it’s beyond language. It’s silence. Music. Love. Life. That’s beyond language. And you get it clearly in the West with the towering T. S. Eliot. You see, Eliot is somebody I have profound respect for, even though he and I have deep ideological disagreements. Remember in “Burnt Norton” when he talks about words? The raid on the inarticulate, the raid on the ineffable. He talks about how words break, slip, slide, won’t stay still. There’s got to be something so much deeper than the words, and of course, the Four Quartets themselves, modeled on Beethoven’s opus 132, are an attempt to get at a music that’s so much deeper than words in the language.

It took him a while to get there, whereas for Black folks, we start there because for 244 years, we couldn’t even gain the right to learn how to read or write. So it’s going to be in the music, in the organization of a sound that constitutes all of one’s humanity, creativity, genius, talent, ways of constituting bonds, camaraderie, gemeinschaft, face-to-face relations. So that you can convince the people not to kill themselves, not to commit suicide, collective suicide. Because this is beyond the absurdity of Camus and Sartre. This is about as concrete as your mama being raped in front of your eyes. Absurd doesn’t capture that. There’s an absurd dimension to it, but it doesn’t capture the concreticity, the specificity of it. All you could do, like at the end of King Lear, is howl. All you can do is shout. All you can do is moan. All you can do is groan. All you can do is cry.

And then you transfigure that into the language of story. Of course, given the role of the church, and given my own bias as a revolutionary Black Christian, and the stories of our Jewish brothers and sisters who unleashed them into the world with Hebrew scripture, and unleashed into the world a New Testament Palestinian Jew named Jesus, a Roman Jewish brother named Paul—that provides a focus on the least of these, spread to chesed, to orphan, widow, fatherless, motherless, to the persecuted and subjugated. We should have the same critiques of any pharaohs, and Black folk were very taken by those stories, profoundly taken by those stories.

Hill: Brother West, I want you to finish that thread, but I want you to add to it. If you can maybe center this, not only have you taught people how to bear witness—and you mentioned your revolutionary Black Christianity—but in one of your most recent books, you talk about living and loving out loud as well as the radical elements of Black political culture. What I would love for you to talk about, as someone who is a revolutionary Black Christian but also a radical, Black, prophetic voice, a visionary prophetic voice. I really want you to help us to understand: What is most concerning to you, right now, in this moment in the world, but especially in this country, culturally? Can you talk about it, given that prophetic vision? And once you’ve talked about that, I would love for you to talk about why that has inspired you to be a real voice in the 2024 presidential election. I think we know why it’s more critical than ever that we bear witness, so I want to give you free rein and take that wherever you would like.

West: There’s a wonderful line that T. S. Eliot has in his essay on F. H. Bradley, the great philosopher, who he wrote a dissertation on, where he says, our moment is so grim that it’s not simply a matter of trying to be part of a tradition, but trying to keep alive the very memory of the tradition. Now, his tradition is in many ways different than mine. He’s got a traditionalist understanding of tradition. I’ve got a revolutionary understanding of tradition. When I think of tradition, I’m thinking more on the chocolate side. I’m thinking of Frantz Fanon’s Wretched of the Earth. I’m thinking of the resilience of oppressed people all around the world. He’s thinking of Homer, Dante, Shakespeare, Goethe, and so forth. I love those figures too, but I always dip those figures into my own chocolate experience and my own tradition of resistance and resilience.

One of the reasons why I’m spilling over—because my calling is still the same, my vocation is still the same, and it will remain the same till the day I die. (gesturing toward his black suit) I’ve got my cemetery clothes on, coffin-ready every day, because you try to tell truth and bear witness and pursue justice in a deeply white-supremacist world, you got to be ready to die any minute, because death threats are always there. So the question becomes, How does one best keep alive the memory of those who came before, so that the younger generation can have access to moral and spiritual greatness? That’s Fannie Lou Hamer, that’s T. R. M. Howard, that’s Martin King, that’s Rev. C. L. Franklin, that’s my grandfather, Rev. Clifton L. West Sr., pastor of Metropolitan Baptist Church on the chocolate side of northeast Tulsa. A lot of times that greatness is not associated with people who are well known, but I know what greatness is, given my own biases, because this is a hermeneutical circle that we’re in. You see, I love to talk about greatness. I know Brother Trump talks about greatness too. He talks about Alexander the Great. I’m talking about Jesus. I mean, one is running the money changers out of the temple and being put on the cross. The other is defined in terms of conquest and domination and subjugation.

The choice is love or hate back.

I don’t shy away from ἀρετή (arete), I don’t shy away from greatness and excellence, but I have my own definitions of it. I just want to be able to bear witness to the greatness of those people who forged such a magnificent tradition. And it’s not a function of skin pigmentation at all, because you’ve got a lot of Black cowards, a lot of Black thugs, a lot of Black gangsters, a lot of Black folks who shun virtue and shun sacrifice and shun service. That’s a human thing, but it’s tied to skin pigmentation to the degree to which Black people in a white-supremacist world have to deal with chronic hatred. And the choice is love or hate back. You got to deal with chronic terrorism. The choice is freedom for everybody or a Black version of the Ku Klux Klan. Everybody got to deal with trauma; the choice is wounded healer or wounded hurter. Everybody got to deal with sorrow; the choice is Louis Armstrong, joy spreader or sorrow promoter. Those are profound questions that sit at the center of education, sit at the center of paideia, sit at the center of what it means to be human, sit at the center of how we’re going to bequeath this to our own kids, to the younger generation, the students in our classes, and so forth. Not to indoctrinate, but to make available to them these grand examples who bore witness to a moral and spiritual greatness.

For me, one of the ways of doing that right now is to spill over into presidential politics and say, Y’all gonna hear a whole lot of language of Martin Luther King and Fannie Lou Hamer. You’re not used to that in politics. How come? Most of these politicians are bought off. Most of them are cowardly. Most of them are well adjusted to injustice. Most of them are accommodating to the unjust status quo. They’re not used to that. (whispering) “Brother West, we understand there’s prophetic fire and things, but you in the wrong lane—politicians do this, and the so-called prophetic folk do that.” Really? Okay. That’s like saying Coltrane ought to just stay in the Apollo rather than go to Carnegie Hall. But when he goes to Carnegie Hall, he’s gonna play “Love Supreme” and “Alabama” as well as “My Favorite Things,” the same way he plays it in the Apollo. Presidential politics supposedly is confined to only certain kind of persons with a certain kind of language and discourse, with limits and circumscribed constraints, and you don’t raise certain kind of issues, and so on.

That’s like saying Coltrane ought to just stay in the Apollo rather than go to Carnegie Hall.

As you know, this campaign is about dismantling the empire. Eight hundred military units around the world. Viewing the United States as a nation that can be tied to moral and spiritual greatness, as a nation among nations, not an empire that other nations have to defer to based on our corporate interests. It has to do with the best of America, which is multiracial, of course, multigender, and so forth. But it has everything to do with the focus on the least of these that you talked about. It could be Rabbi Heschel. It could be Dorothy Day. It could be Vito Marcantonio, the great lawyer for Du Bois. Or it could be John Brown. It could be Du Bois.

In some ways our greatest—I want to be very honest about this—our greatest intellectual, who is a Black metaphysician as well as a musical and lyrical writer, is Toni Morrison. The only one who comes close was born in this part of the country: Ralph Ellison from Oklahoma City. But Toni and her new book, The Source of Self-Regard. My God, I think it’s the best thing. It’s even beyond Ellison’s Shadow and Act. I didn’t think we’d see a collection of essays that dug at the profound depths of what it means to be human, looking at it through a chocolate lens. Shadow and Act, for me, was always the deepest in the essay form. But Morrison’s Source—Lord, have mercy—puts her in the same zone as Melville and Faulkner. And that’s a very rarefied space because the American Empire is not known for its great literary productions. We’ve had some great ones, but compared to the Russians, compared to Tolstoy, Dostoevsky, Chekhov, Leskov, Turgenev, and the others, we’re in the minor league. But with Toni coming out of this great musically centered culture, to be able to translate that at the level of novelistic expression, for me is one of the great, great moments in the history of the last fifty years, artistically speaking.

Hill: I really want you to lean as much as you can into what’s most concerning pressing, pressing on you. And then if you could also talk about what you’re potentially bearing witness to in this campaign that’s more than a campaign.

West: It’s a moment and a movement.

Hill: This is what I say, Brother West, and this is how I’ve been able to use something that you’ve said to inspire something, a new idea. I tell students, I want to teach them to learn to care, and bearing witness teaches them to learn to care. Learning in the interest of caring, not just in the interest of learning or to get a job or, or even to get a job to make a good impact. But to always be centered on bearing witness to something, caring deeply about something, not necessarily deeper than yourself, but somebody.

West: Yes, that’s what it’s all about. Part of it, you see, is that when I talk about this tradition, that we’re losing even the memory of it, it has to do with spiritual decay and cultural decadence. Spiritual decay, for me, is a callousness toward the suffering of others, especially the most vulnerable. Moral decadence, for me, is cowardliness or complicity or conformity to evil or structures of domination. On one hand, you got to have the care that you talk about. On the other hand, you got to have courage. Part of our professional managerial class, to be incorporated within that class, too often is one of becoming conformist to the protocols of the guild. And becoming complacent and even complicitous and sometimes downright cowardly when it’s time to take a stand, because your career or the next opportunity always looms large, rather than principle, integrity, and really caring.

I tell young folk all the time, there’s a wonderful line in Reinhold Niebuhr’s classic Moral Man and Immoral Society (1932), which is the greatest work in revolutionary Christian ethics, where he says, any justice that’s only justice soon degenerates into something less than justice. If justice is just a career move or if it’s just a rhetoric or language that helps you in your profession, you can rest assured it’s not cutting deep enough. What cuts deeper than justice? Genuine care, genuine concern. I call it love. I say, justice is what love looks like in public. It’s partly a critique of justice, ’cause justice is crucial but has its limits. What is the Roman symbol of justice? The blind woman. We’re not talking about the blind woman, we’re talking about the caring grandma, you see. We’re talking about the sacrificial granddaddy. We’re talking about mom and dad. They ain’t walking around blind, they’re keeping track of the little child. You know what I mean? There goes that little Simon boy. There goes that little Hill boy. We’re zeroing in on them. We really care about those little brothers. See, that’s deeper. That’s what keeps justice alive. That’s why Black love is always much more deeper than the struggle for Black justice. If you have Black love, then the justice is gonna flow.

It’s like when I see my dear brother Ibram X. Kendi. You know, I love that brother. He’s P.K., you know, he’s a preacher’s kid, coming out of the same Black church tradition as I do. A different denomination—I’m a hang-loose Baptist, and he’s something else—but you keep talking. “We’ve got to be antiracist.” No, I’m not primarily antiracist. I love Black people deeply, and therefore I have antiracist behavior. But that comes later. That’s like the second or third step. My first step, my first leaning, is the care that you talk about. And that’s the bearing witness. James Baldwin understood. James Baldwin was one of the greatest love warriors to come down the pike. And you remember that wonderful essay he wrote on “Sweet Lorraine,” talking about that genius from the south side of Chicago, Lorraine Hansberry? He says, Lorraine and I always got together, and sometimes they danced together. (I think Lorraine had a little bit more rhythm than he did.) He said, we talked about the difference between making it and keeping the faith. And keeping the faith is bearing witness. Making it is another Black face in a high place, professional success. And there’s a quarrel between professional success and spiritual and moral greatness. The younger generation has been told that the end of life is professional success.

Keeping the faith is bearing witness.

That’s how Barack Obama becomes a hero because he’s the most professionally successful Black man in the history of Black America. You know, I appreciate the brother, and I critically supported him and so forth. But I tell him all the time, I say, Brother, you know, you ain’t close to Fannie Lou or Martin, man. No, it’s hard for you to even shine Malcolm’s shoes, because Malcolm was not about professional success. When he died he had $151 in his pocket, period. But he had so much love and willingness to serve and sacrifice flowing out of him. Whereas President Obama: talented, polished, brilliant, sophisticated. Yes, but that’s success. That’s qualitatively different than greatness. You ask any of the jazz musicians, some of the most successful folk in jazz are not Charlie Parker, John Coltrane, Sarah Vaughan, or Ella Fitzgerald. Some of them were, but some of them were not. Take Dorothy Donegan, who was the pupil of the greatest jazz pianist, Art Tatum out of Toledo. Art Tatum used to say, Dorothy’s the only one who makes me practice. When another genius, Oscar Peterson from Montreal, heard that, he said, that’s where the standards are. The world don’t know about Dorothy. But the greatest of all the jazz pianists put her alongside him. She set the standard. That’s greatness. She was not successful at all. And there’s so many others, like Eric Dolphy, Albert Ayler, and others. These are just towering, unbelievably great folk who were not successful.

And it’s greatness that our young people need to focus on. It is not just the successful ones, you see. That’s part of what it means to try to bear witness. It’s not about you yourself. You know, I tell my young people all the time, I say when they look at anybody, when you look at me, if you can’t see the best of Irene and Clifton (my mom and my daddy, I’ll never be as great as they were), if you can’t see some of Martin in me, if you can’t see some of Curtis Mayfield in me, if you can’t see some of Aretha in me—all of these are the ones who constituted who I am. And if you see them in me, that gets my ego out of the way. And in a certain sense, you know—I hate to use this language in the literary, philosophical context, but I believe it—it’s piety: the sources of good in one’s life from womb to tomb. And piety gives you a sense of indebtedness, a sense of gratitude to Mom, Dad, Grandma, Granddad, Rev. Willie P. Cooke, the pastor of Shiloh Baptist who baptized me. I will forever have a deep sense of gratitude for them. As long as they’re inside of me, then it means that I’m trying to get out of the way. And they can see whatever love, integrity, honesty, courage they put in there, because nobody does it on their own.

Aeneas carrying his father is the great example of piety in the West.

It’s like in The Aeneid, where Aeneas is carrying his father, Anchises. That’s the great example of piety in the West, you see. He’s carrying his father on his back. He ain’t heavy, he’s my daddy. You get it in the great Tobias Smollett’s last novel, The Expedition of Humphry Clinker, where you get piety from below. Humphry Clinker was a lower-class brother. He’s always tied to the debts he has to pay and the gratitude he has to pay. You get it in a Laurence Sterne who says, my master is Rabelais, but the greatest one in Cervantes. If you all think I’m somebody, take a look at Don Quixote. Take a look at Gargantua and Pantagruel. Oh, my God. Probably one of the greatest moments for me in the history of the early modern West in this regard is the letter that Rabelais writes to Erasmus right before Erasmus dies. You get the towering literary figure and genius in early Europe with the towering public intellectual. Rabelais says to Erasmus: you’re not only my mother but my father. See, I don’t exist without you. You are the unconquerable champion of truth and the sustainer of the freedom of letters.

Now, you can imagine: what is that like on the side of town where people are hated and terrorized and traumatized? A similar dynamic, but a very different lens through which they view the world. But it’s still essential for any human project. In Rabbi Heschel’s great essay—the first essay he wrote in English when he was coming from Jew-hating Europe, called “An Analysis of Piety” (March 1940), it is remembrance, reverence, resilience. What is prayer? Revolutionary acts that subvert and create moments of disruption in patterns of domination. Or think of James Melvin Washington, who is the closest brother I ever had other than my blood brother. His great book Conversations with God, a history of Black prayers, put a smile on Ernst Bloch’s face. You want to get some utopian projection going on here? Look at those prayers and see how subversive and revolutionary they are. The freedom dreams.

I’ve taught in prison for forty-one years, and the anthem of the brothers in prison is the Commodores’ “Zoom.” The freedom dreams that Robin D. G. Kelley talks about. What do you want to do? I want to fly away. Toni Morrison talked about folks flying back to Africa. Ralph Ellison’s most famous short story is “Flying Home.” There’s a history of trying to get some distance from this pain. For what? To be treated like a human being and not be violated and lynched and so forth. Freedom dreams. That utopian energy is unsuffocateable. You can’t snuff it out. You can’t eliminate it. It might weaken it and alleviate it, but you can’t eliminate it. People still dreaming. Take Lionel Richie. Remember, that song was written when his closest partner’s wife just died. He and Ronald LaPread wrote the song together. His wife had just died. That’s catastrophe. In the face of catastrophe, what you gonna do?

I’m sorry to go on and on, but you got me all fired up.

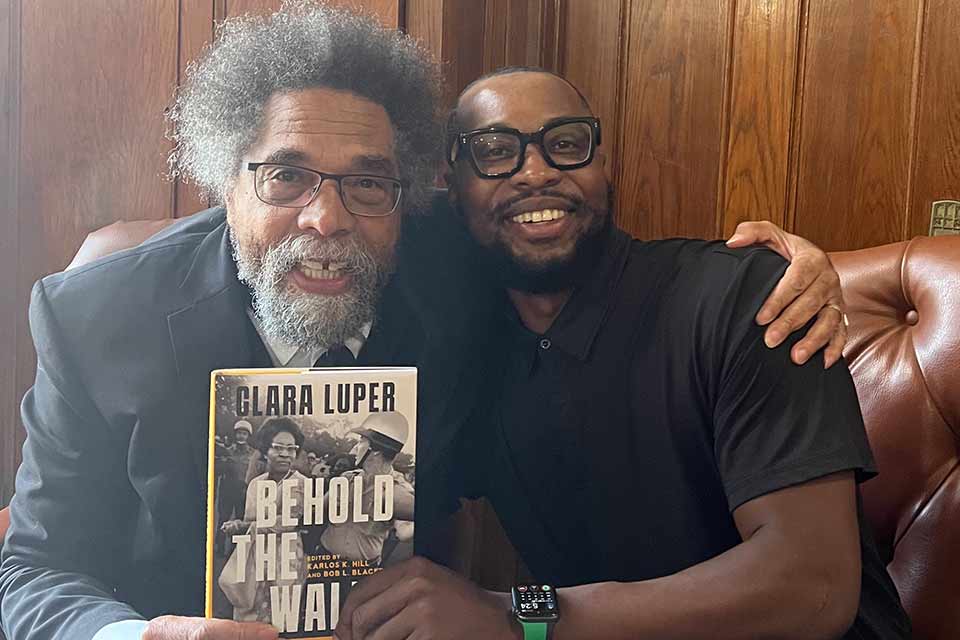

Hill: Brother West, I just wanted to share a book with you. This is a gift to you: Clara Luper’s Behold the Walls. I know you are familiar with Clara. The book had been out of print for at least a decade.

West: I saw on your Twitter feed that in the last couple of days, you had an anniversary?

Hill: Yes, the sixty-fifth anniversary of the Katz Drugstore sit-in. We brought together many of the original thirteen participants in that Katz Drugstore campaign that led to the desegregation of fifty-three stores in 1958. We brought them together to remember that, but also for a documentary that we hope to be able to pitch to the History Channel or PBS. To tell the story, to help do what needs to be done, which is to help the world understand what Clara Luper bore witness to, her profound legacy. On the sixty-fifth anniversary, not only did we get her memoir of that movement republished, but we also had a teachers’ institute in Oklahoma City where we brought together sixty-five teachers to do a workshop based on this book to help them figure out lesson plans and curriculum around Behold the Walls, her memoir of the movement. We had them here for a week. The point I’m driving home is that we focused on two concepts in the Clara Luper Teachers’ Institute. First, freedom’s classroom: Clara Luper as a master history teacher, someone who taught them so much about how to fight, how to struggle, how to be in service to people. And also how, as someone who was a devotee of Dr. King and Gandhi, she really inculcated in her students not just nonviolent disobedience, but she really impressed upon them the need for radical love.

West: Is that her language?

Hill: She doesn’t use the language of radical love, but what she tells them to do is engage in radical love. She tells them, she coaches them to endure the abuse, the mistreatment. Because we’re not here just to desegregate these lunch counters, we’re here to help the very people who are oppressing us. We can stand here and, through radical love, love people who don’t love you. Love absolutely.

West: That’s the kind of love I love. That’s it.

Hill: Brother West, that’s where I’m going. I would love for you to just talk about radical love, Clara Luper’s radical love, and the transformative impact that it can have on the catastrophes you mentioned earlier.

Acts of radical love are higher forms of courage that try to push back the wretchedness that is so dominant inside of all human beings.

West: I’m just convinced that human beings are wretched in so many ways. The history of the species is very much the history of structures of domination, histories of hatred, what the great Howard Thurman called the hounds of hell unleashed: hatred, greed, fear, resentment, envy. I have a very grim philosophical anthropology, in some sense. Christians call it sin, but on the other side of that wretchedness, there’s a wondrousness and wonderfulness, like that last line of Chekhov’s great short story, “The Student,” reflecting on Easter. How is it that this wonderfulness, this wondrousness, can still be found given all the blood in human history and all the wounds in the history of the species. For me, acts of radical love are higher forms of courage that try to push back the wretchedness that is so dominant inside of all human beings. I do believe that there’s a civil war taking place over the soul of every person. They have to make a choice. When you choose not to hate back, therefore, what you’re doing is trying to elevate the relationship, the tradition, and the future to a level of moral and spiritual greatness that might not have the chance of a snowball in hell, in terms of its consequences. That will be a shining example of an integrity that could touch people’s hearts, minds, and souls to keep the tradition alive.

You see, it’s not utilitarian calculation, it’s not just political strategy. It’s at the deepest level of what it means to be human. That’s Sister Clara. That’s Martin. That’s Coltrane’s Love Supreme. That’s Stevie Wonder’s “Love’s in Need of Love.” That’s the love. That’s what Baldwin says about love: it forces us to take off the mask. We know we cannot live within, but fear we cannot live without. That’s existential. You don’t need a lot of Kierkegaard, even though that Danish genius helps. But Baldwin, he’s working this out in his own distinctive way with his own genius. That’s the kind of radical love I’ve always been committed to.

That’s why in the end, back to the twenty-fifth chapter of Matthew where you talk about the least of these, it will never make sense through the eyes of the world, the dominant ways of the world. It will never make sense because in the dominant eyes of the world, it’s Thrasymachus over Socrates—might makes right. Power dictates morality. Socrates has an integrity he’s trying to pass on to the younger generation in The Republic. Glaucon and Adeimantus, let me give you an example over against this gangster who’s trying to tell you to conform to the dominant ways of the world. Thrasymachus has all the evidence in the world.

Hegel says history is a slaughterhouse, you know? Gibbon says it’s a series of human crimes and follies. They’re right—in part. But there’s something else too. Clara will tell you what that something else is, not by means of utterance solely but by her example. I mean, she lives it. That’s a very different thing. Like the conclusion of an Aristotelian practical syllogism; it’s not a proposition; it’s a life lived. That’s the conclusion I would see. Now, I don’t know her background. She’s probably a church sister.

Hill: Well, what I say to people, trying to help them understand, is that Dr. King was a minister/activist; Brother Malcolm was a minister/organizer; and Clara Luper was a teacher. That’s where she was rooted. She wasn’t rooted in the church like Dr. King.

West: Was she shaped by growing up in the church?

Hill: She was. She preached radical love because it came from a Christian ethos.

West: Her soul craft. Do you remember the name of her church?

Hill: Yes, we had our final program for the sixty-fifth anniversary on Sunday at Fifth Street Baptist Church in Oklahoma City. What we’re trying to accomplish with Clara Luper is to get people to see her as a master teacher. And we taught the teachers in the institute that the era of the master teacher isn’t over, and that even in an Oklahoma that’s banning books, that’s stifling creativity, stifling just the whole environment. Deborah Gist, the superintendent of Tulsa Public Schools, has been harassed, harangued, and finally she gave into that and resigned her position because of refusing to be silent about what’s happening. So, she’s one of the fatalities. It’s not just the teachers, it’s also the administrators. We’re reminding them that there are courageous people like Clara Luper, master teachers who center radical love both in their activism and their teaching, centering students. Clara Luper called her students diamonds. It’s trying to get people to understand.

We tried to do two things this year: the hundredth birthday of Clara Luper, we celebrated that on the steps of the state capitol, which was really important to highlight unity in the community. That’s something that Marilyn Luper, her daughter, thought was important. The second thing is the sixty-fifth anniversary of the Katz Drugstore sit-in, and bringing together those activists to reflect on how that one sit-in helped galvanize the Greensboro sit-in in 1960. And that’s the link which makes Oklahoma really matter in the national story: through the NAACP network, because the activists in Greensboro are part of the NAACP Youth Council, they learn about the success of sit-ins from Oklahoma City.

Part of what I’ve been able to bear witness to is we have been able to assemble all the documentation to show that. So, it’s not just the memories of Marilyn or the memories of some of the activists. We actually have NAACP minutes showing the ways in which that there was a presentation from the Oklahoma group in 1959 at their annual conference, where they won an award for the youth council chapter. And the news of their success was shared there. From there you see, not necessarily a direct line, but what Marilyn and many try to say is that a successful precedent was established, news of its happening. And then you saw, months later, Greensboro emerge and then the rest.

West: I was just talking to Brother Amos Brown, the pastor at San Francisco’s Third Baptist Church for forty-nine years. He took that church over after Freddie Haynes, his father, dropped dead in the pulpit. This is the Freddie Haynes whose son just took over the Rainbow Coalition of Jesse Jackson, pastor of Friendship–West Baptist in Dallas, Texas, for the last thirty-five years. Amos was at that NAACP meeting, either in New York or somewhere on the East Coast, when there was a presentation reflecting on what was going on in Oklahoma City with the folk from Oklahoma City. And the young brother who was sitting there was the brother who went back down to Greensboro, where it didn’t take off at the first meeting in the fall. Then, at another meeting in January, it did take off. But there was a direct line because that little young brother was sitting up there in the meeting when they were reflecting on it at the NAACP gathering. And Amos Brown was in that same meeting. You know Brother Amos, right? He knows that history, doesn’t he?

Hill: Yes, he does. We had him speak at the sixtieth anniversary.

West: Is that right? See, you’re light-years ahead of me.

Hill: No, sir. I just I just know these people, they’re a part of this community, trying to lift up this story.

West: That’s exactly right. He’s always the first one to say, don’t talk to me about Greensboro if you don’t know nothing about Oklahoma City. That’s his thing. He didn’t get into Miss Clara’s name. He just talked about the group.

Hill: Yes, she was all about the students. And the students were, you know, her diamonds, diamonds in the rough, right? You know, the radical love of Clara Luper was that she believed each of her students, no matter what, had amazing potential. You just had to spend the time with them to illuminate it. She had this radical belief that everyone could learn and everyone could reach their full potential. What was radical about her is she truly spent the time to mine it, she really did.

The radical love of Clara Luper was that she believed each of her students, no matter what, had amazing potential.

West: It reminds me of my mother, actually, Irene B. West—there’s an elementary school named after her right outside of Sacramento. She was the first Black principal, and the first Black teacher as well, in the school district. She was known for being the teacher in the vacation Bible school in Shiloh Baptist Church, right there in Oak Park, which is like the south side of Chicago. The young kids would come in from outside of the church. She did that for so many generations that you could just walk through the community and someone would say, oh, that’s Mrs. West, I remember she taught me when I was nine, I was eleven, I was thirteen. And she let us into the church even though we weren’t members of the church because they had food and everything. Between 9:00 and 12:00 they had these little gatherings, and that kind of impact of being a care lover and tenderer of young people’s hearts, minds, souls, and bodies, that’s what greatness is. That’s it. It doesn’t get better than that.

Hill: And Brother West, when you talk to Marilyn Luper about who her mother was, you can talk about a lot of different things. How she went to jail twenty-six times. Or you can talk about not only her central role in the sit-ins but also in the sanitation strikes or running for the US Senate, her radio program. But what Marilyn wants to talk about, going back to her mother’s selfless devotion to her students, is for fifty years she took a group of students, as many students that wanted to go, to the NAACP National Conference, members of the Youth Council, she always took upward of fifty-plus students who never, ever had to pay for a hotel room, never had to pay for a flight, a bus ticket. She found a way. This is what Marilyn said. She found a way every year for fifty-plus years.

West: Oh, my God. That’s it. That’s the bottom line right there. That’s what Ashford and Simpson would call the real thing. That’s the real thing.

August 2023

Editorial note: Dr. Hill’s conversation with Marilyn Luper Hildreth, in honor of the centennial of Clara Luper’s birth, appeared in the May 2023 issue of WLT.