Artists of Iraqi Descent Celebrate Roots and Global Belonging

Four artists of Iraqi descent are achieving global recognition for their paintings and handbag design. Both proud of their culture of origin and open to resources beyond national designations, these four artists are reckoning with vibrant identity issues.

The careers of four artists of Iraqi descent recently witnessed significant events. One American, Maysaloun Faraj, and three Europeans see these events as defining moments to reflect on roots and belonging to a global culture. Two of the artists are British painters, Suad Al-Attar and Athier Mousawi, and one is Italian, Hussain Harba, a world-class designer of women’s handbags and novelty furniture items. All four are well established, with works and products in world museums and in private collections.

Faraj had a solo exhibition in Paris in 2022, and Al-Attar’s granddaughter, Nesma Shubber, published a book on her grandmother’s life and art, Suad Al-Attar (Heni, 2022). In April 2023 Harba won the Industrial Compass Award, one of Europe’s prestigious design prizes. The youngest of the group, Mousawi had a solo exhibit last June in the arts hub Cromwell Place in central London. With roots in the Middle East, Paris, Los Angeles, and London, these artists showcase facets of a fascinating global art scene.

Undoubtedly, cultural interactions impact individual and collective identities, and that clearly shows in the artists’ works. Achieving recognition in a global setting with intense professional and ideological contentions requires openness to influences. Although all four artists show pride in their culture of origin, they make their mark due to embracing artistic resources well beyond national designations. A closer look at Faraj’s and Al-Attar’s books, and Harba’s and Mousawi’s recent works, illustrates an intriguing reckoning with vibrant identity issues.

Maysaloun Faraj: Art and Social Media

Faraj’s solo exhibition in Paris in June 2022 was at the Mark Hachem Gallery, with a companion catalog. Maysaloun Faraj: HOME Lockdown, 2020–2022 is richly illustrated, and it comes in numbered copies signed by the artist. Based on works done during the sheltering in place due to Covid-19, the paintings appeared on a group Facebook site dedicated to making home a subject for drawings and paintings. For an international community facing a global pandemic, the social media platform turned home into a locale for scrutinizing issues of belonging to a certain place and the possibilities of creating communal connections beyond that space. Started by Faraj herself, the Facebook platform also demonstrates the effects of one artist’s engagement with communal responsibilities.

In dozens of small and large paintings, Faraj offers intriguing conceptualizations of home as a flourishing and comforting environment. The community of that Facebook group, “Stay Home, Draw Home,” seems to participate in some collective imagining of what it means to stay home and what it means to reinitiate affinities with physical and metaphorical spaces. Despite the uncertainty and turmoil of that pandemic period, there has been an abundance of solidarity across communities fractured by an overwhelming challenge.

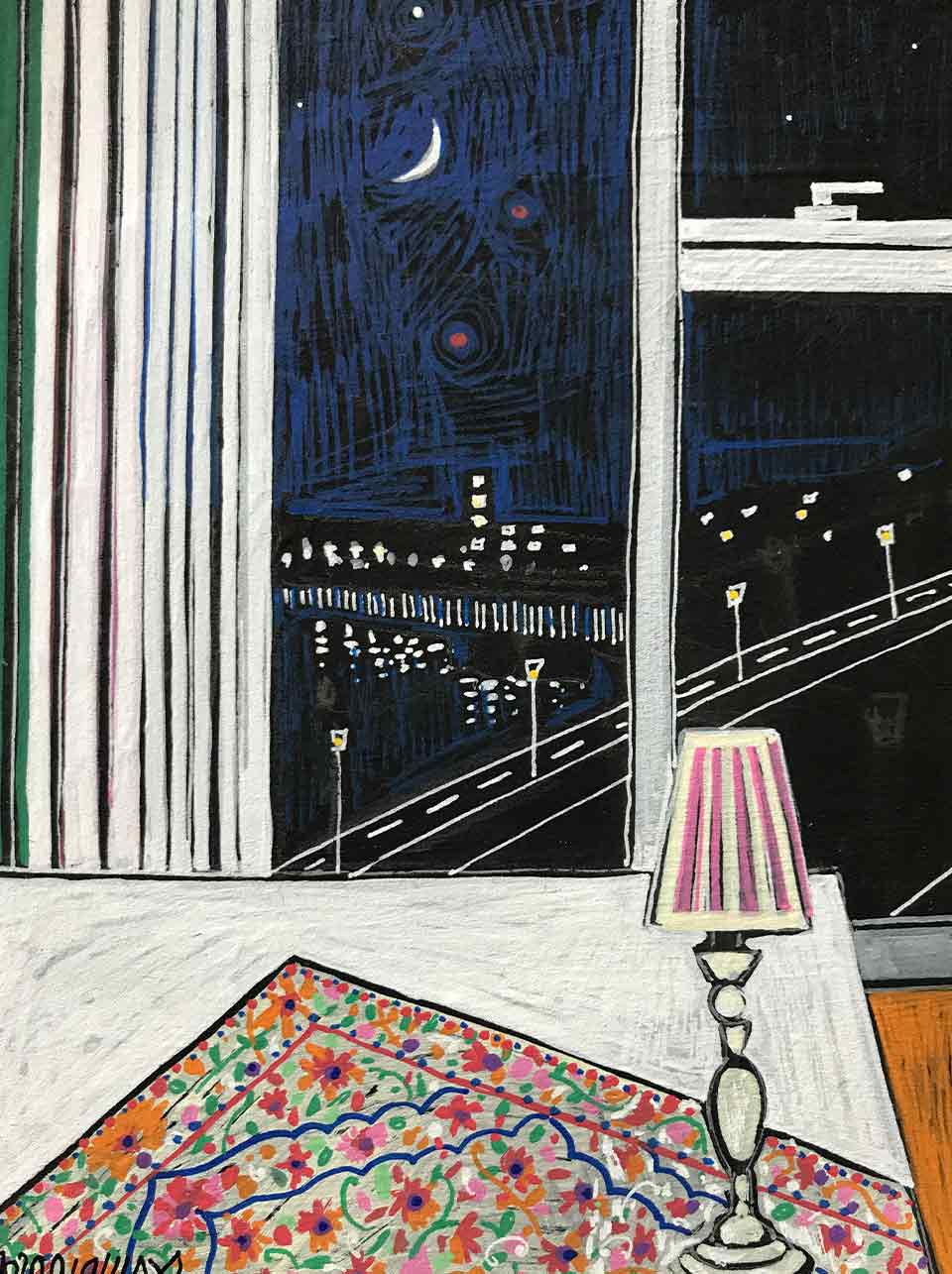

There is nothing new about bonding during stressful times, but scrutiny of home as a physical and metaphorical space can easily turn into an examination of roots and identities when the home culture rubs shoulders with global contexts. In Faraj’s painting Home 10, for instance, the artist’s bright apartment seems to extend into the equally bright nocturnal view of the city. Faraj has been living in London for four decades, and she wrote in one of her comments on that page that London feels like home, too. The painting’s bridge might also prompt us to think of the symbolic implications of belonging to a new locale away from a home culture.

Suad Al-Attar

Reading Nesma Shubber’s book on Suad Al-Attar feels like being carried away on a current of intriguing stories of the artist’s life, her times, and the enchanting worlds of her artwork. Al-Attar’s paintings tell stories, and her fundamental narrative structures materialize in a range of contexts and scenes, from utopian gardens and mythical settings to the realism of daily life and struggles. Al-Attar’s paintings are deeply confessional, but what is unsaid is as expressive as what appears in the painting. The untold stories behind many of her paintings must be mesmerizing, and Al-Attar is another Shahrazad aware of the critical weight of silence. Shubber’s book highlights these and more issues, and one of its virtues is allowing the artist’s vision and voice to stay central throughout the book.

Al-Attar is another Shahrazad aware of the critical weight of silence.

Shubber’s extended analyses and comments are punctuated with a plethora of anecdotes derived from the artist’s long career and the writer’s intimate knowledge of her subject matter. Al-Attar is in her eighties, still active and engaged, and she is Shubber’s grandmother. With exemplary discipline, Shubber presents only the most necessary personal details that seem critical to understanding the artist’s body of works. One of these is Al-Attar’s unhappiness with an early marriage, decided by the family and demonstrating the limited authority she had in a patriarchal society. This might explain why paintings of women of brilliance in appearance and essence also seem to come with an odd feeling of broken or perplexed presence.

Identity and belonging are other themes in the artist’s works. Although she has been living in London for close to four decades, her paintings continue to engage what is happening in Iraq. Her works showing Iraqis’ suffering due to the Gulf wars, for example, are moving records of helplessness in confronting historical events of overwhelming ugliness and cruelty. Some of these works were acquired by the British Museum for their permanent collections, and that will consolidate their worth as living testimonies. Al-Attar is aware of the necessity of bearing witness to historical events, and one reason for that might be the death of her sister, also a prominent artist, and her husband by an errant American missile in 1993.

Such involvement with a home culture shows identity as a constant but not a dominant factor in all four artists’ work. It’s not a static identity, and it certainly is not just subject matter. All four artists’ responses to the unusual suffering inflicted on Iraqis since 1991 are also part of their contribution to a global culture with inclusive and humane imperatives.

Hussain Harba

One can imagine Hussain Harba, the Milano handbag designer, falling off the Hanging Gardens of Babylon, rolling into the city roadways lined with date palm trees, and ending with breathless strolls on Europe’s boulevards. His imagination embraces the ingenuity of his native heritage as well as the expertise and professionalism of his European education as an architect and an industrial and art designer. The vision his products reflect is outrageously bold and colorful but equally thoughtful and practical. Perhaps this is one of the virtues of openness to other traditions, and being honored as a designer in Italy might signal appreciation of immigrants’ contribution to their host cultures.

Harba’s are luxury products with a striking visual impact. They are more like art pieces than accessories with recognizable purposes, and hence they often contribute to expressing the personality of those using them. His pursuit of perfection shows in the selection of the highest quality material and in flawless manufacturing. Take, for example, his redesign of the famous 1972 “Joe” baseball glove chair by De Pas, D’Urbino, and Lomazzi for Poltronova of Italy. The chair was named after Joe DiMaggio, but in Harba’s re-creation, its visual appeal might as well invoke Marilyn Monroe. His homelike handbags set themselves apart from other luxury designs due to his perception of women’s need for an intimate item that provides familiarity and comfort.

Harba grew up in an environment supportive of the arts. His family art collection has over five hundred works by twentieth-century Iraqi artists. In Longing for Eternity (Skira, 2013), the book on that collection, Harba says that art has the power to unify communities. This might explain his venture to build a museum in his birth city of Hillah to contribute to the spiritual life of a people and a locale he knew so well, and to which he can only return symbolically through his artistic and professional energies. This is also true of all four artists, who show persistent connection to home culture and whose virtual returns form a sizable part of their personal and artistic lives.

Harba’s family art collection has over five hundred works by twentieth-century Iraqi artists.

Athier Mousawi

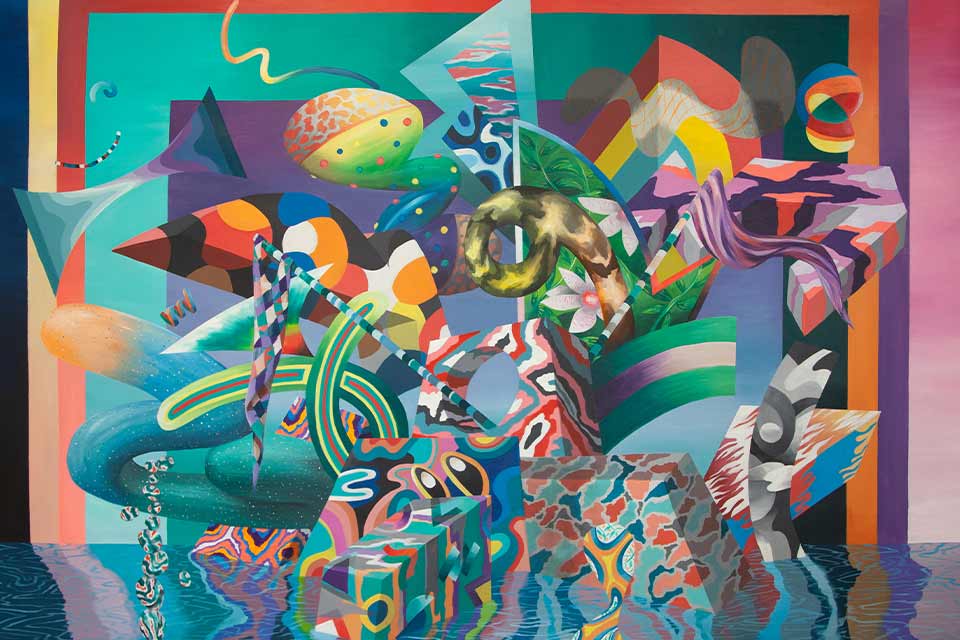

The experience of getting into a painting by Athier Mousawi might feel like waking up suddenly and slowly in a world we didn’t know existed—tangible, three-dimensional, boundless, but curving and looping in myriad directions. Its lines move like waves, lifting and descending, and leaping up again only to merge with others and explode in dazzling formations and shapes. Surreal and too real, these formations look more like sculptures of the things around us. In a world like this, uncertainty rules, and shifting, if not anarchy, is a constant presence. Mousawi’s creations are not the stuff of myth or dreams. They are objects and material we recognize—concrete, plastic, metal, and slabs of marble, along with toys, household items, and the discarded urban objects of an appetite for consumption that seems ubiquitous and unsatiable.

Mousawi’s creations are not the stuff of myth or dreams. They are objects and material we recognize.

The sentiments are equally familiar: lack of belief, nostalgia, ambivalence, anxiety. Mousawi seems content to stand aside and let his creations interact with current ideas and audiences with little or no interference. That’s the artist dealing with colors on canvas, but Mousawi articulates his vision equally well with words. His statements on his projects and exhibitions are key to unlocking the meaning of his work. Commenting on his June 2023 solo exhibition in London, Mousawi said all fourteen paintings deal with just one subject: the melting of false monuments. His purpose, he adds, is to challenge our enduring obsession with commemoration, especially this universal public shrouding of ideological and other ephemeral concerns. Our cherished monuments melt in these paintings, and although still preserving some architectural integrity, their fragile essence dissipates into the ocean below.

Mousawi is by no means pessimistic. His art presents with little interest in lecturing or pretending to know better. The recent paintings, for example, are built on a previous exhibition Mousawi had in Dubai in 2017 under the title All Things Come Apart. Things do fall apart, and Mousawi is fine with that since his vision is not about catastrophic phenomena. His reckoning with the world around him shows an engaged and caring soul. He led art workshops for children in Lebanon, Jordan, Palestine, and the British Museum, and he uses social media to promote matters of social justice. Some of his most touching paintings are about Los Angles—a city he called home for years, and whose essence he captured in masterful portrayals of enduring natural beauty besieged by disruptive forces.

Art can liberate us of vague nostalgia and anxieties that reduce our chances of comprehending what is happening in the world.

The attention and recognition these artists are enjoying indicate the wealth of aesthetic values they bring into their new host cultures. In a global culture that is increasingly competitive and divided, art might be our savior, as the Spanish philosopher Santiago Zabala says. Art can liberate us of vague nostalgia and anxieties that reduce our chances of comprehending what is happening in the world. The contributions of these four artists to the cultural life of Europe, the United States, and the world make our life more interesting and rewarding. Perhaps this is what Zabala means by saying only art can save us.

Boston, Massachusetts