My Hajj

The tears, the rituals: a family goes on a journey and joins millions of strangers pouring into Mecca. In this moving essay, a writer evokes the beauty, movement, and emotion of the Hajj itself.

In the beginning, there was the gravity of the call: And proclaim to the people the Hajj; they will come to you on foot and on every lean camel; they will come from every distant pass (The Qur’an 22:27). We answered as a family. All five of us. We were pulled out of our Nordic home to complete the circle of faith. Like a boomerang that throws itself out only to return to itself. A homecoming. I’d been feeling so old for years and dreamt of being buried in Mecca like men and women from old tales. But Hajj wasn’t going to be that kind of story.

The story of Hajj begins with your last will and testament. I asked people on social media what they wanted me to leave them. I didn’t say why. They took me for my regular joking self while I was burning with the desire to finish my life in that holy place. I sat with SonNo.1 watching Swedish woods and told him I had nothing to leave them. Whatever I possessed would be regulated by state laws. I hoped that my writing would someday be enough for a few Swedish fikas. I named the person I entrust with sorting my unpublished mess. I didn’t say I hoped my legacy to them was this family Hajj. A memory of my love. I imagined them without me, and I was missing them already, and I cried.

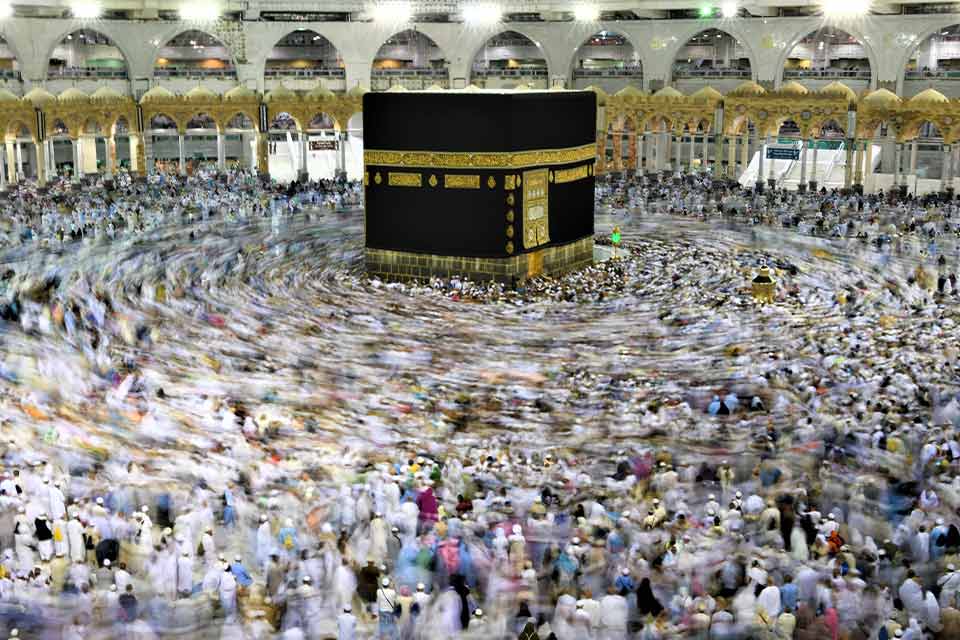

I cried on the plane from Stockholm when everyone was asleep or watching movies. Cried in Istanbul while waiting for the delayed flight to Medina. Cried when some of the passengers were not let onto the plane because of visa issues and again when they fixed them. Cried at the passport check. At the first sight of people streaming into the Prophet’s Mosque. When I met friends I didn’t know were there. On the bus to Mecca when our guides sang Bosnian Nasheed songs. At first sight of the Kaaba. During our first tawaf around the Kaaba and at that first Fajr prayer outside Masjid Al-Haram as both men and women formed rows in ways I’d never seen before. At the break of dawn.

I didn’t cry because life was hard and unjust or because of past traumas or self-pity. That was new.

From the onslaught of weird tears to the rituals, you will always be unprepared for Hajj. The guides will serve you practicalities and leave you to figure out the narrative as you become a character in that story: a family goes on a journey and joins millions of strangers pouring into Mecca.

The guides will serve you practicalities and leave you to figure out the narrative as you become a character in that story.

Hajj is the fifth pillar of Islam and the end of the cycle that begins with the Shahada, the simplest aspiration unbound by spacetime, over the five daily prayers, the fasting of Ramadan, and the zakat tax, to the stunning testimony of will set in one place at a prescribed time, only to come back to that original aspiration: La ilaha ilallah. There is no other divinity except God.

Hajj is the walk in the shoes of God’s friend Abraham, who built the Kaaba with his outcast son Ishmael. The ultimate testimony of faith. Your intention, the niyah, must be pure, and your material

commitment absolute. Every step, from the struggle to purchase a package, over the logistical problems and the global cocktails of germs and viruses and fungi, to the tasking rituals; everything asks you to ride the waves of life. The prices had doubled this year, which meant we spent all our savings as people did once upon a time. Sons No.1 and No.2 had saved for themselves. Growing up in Bosnia, I knew people would do Hajj at an old age, as the cleansing before death. I’d never heard of young Hajjis, let alone children as young as my Aida, who’d recently turned twelve. Wife and I surely had some sins to work on, but the children would get an ocean of spiritual wealth. I wanted this for them.

It is in Medina you first realize that the Saudis cool open spaces. The Enlightened City of the Prophet was our first port of call, where I understood the importance of the complex play between mandatory rituals (fard) and traditions (sunnah). Hajj itself was a poem, short and intense. The sunnah made it an iceberg of a short story with the buildup to a climax and a fade-out.

The Prophet’s Mosque was a relaxing and egalitarian place. You were lost in the open maze though you always saw the exits. No spot was more attractive, even if you sat right behind the holy Rawda, the closed-off area of the first mosque and the Prophet’s house where he and his two closest friends were buried. The women in our group got into Rawda easily, while for us it took hours of buttering up guards. #Bosnian helped. We got in before the morning prayer and said Selam alaykum ya Resul Allah as we passed the Prophet’s grave and exited the golden gate into the court with palmlike mechanical umbrellas, where big grasshoppers rushed into the lights, died, and were removed by hundreds of Asian cleaners. People kept asking us for selfies, especially with SonNo.1, who was like that fresco image of a blond, long-haired Jesus, breezing through the crowds. Within days, SonNo.2 was infamous for his haggling skills.

In Medina we had a lecture on the ihram, the first requirement for Hajj, but also the short preparatory ritual, the Umrah, which you do upon arrival in Mecca. By ihram, people usually mean two white sheets that men wear, like those you’re buried in. I focused on the techniques of wrapping the unwieldy ihram and sitting down without exposing certain parts. Women could wear whatever they choose. But ihram is really a state of being. It consists of an intention to do the Hajj or Umrah. Then there are prohibitions against wearing perfume, having sex, marrying, hunting, and harming anything. The absolute level of patience. No arguing. No complaining. That is ihram. I told our guides as far as sex goes, I’d entered the state of ihram when I bought the package and would exit when I return home.

On the way to Mecca, SonNo.2 asked where the sand dunes were. He’d imagined a dreamworld of the Orient, but nothing was attractive the way we Bosnian-Swedes are used to in both of our Paradise-looking homelands. We saw date palms in Medina, but the landscape on the way to Mecca was like Mars. I saw some artificial grass. No green mountains. No rivers or waterfalls. No lakes. No endless fields of wheat or corn.

Once in Mecca, we first performed the Umrah, which only requires the ihram, a tawaf around the Kaaba, Sa’y (walking seven times between the hills of Saffa and Marwa), and a haircut. We approached the entrance of Masjid Al-Haram with our eyes lowered, chanting Labbayk Allahumma, labbayk until we saw the House of God, the golden calligraphy on its black veil, the Kiswah. I could barely see it through the tears. The big cube in the white marble court, surrounded by the three-story ring, was like a black hole, and the crowd circling counterclockwise around it was dense. The event horizon. SonNo.2 kept squeezing our hands, but after the third circle, it looked like he was floating in front of us, with plenty of space around him while people pushed us like blades of grass. The most effective weren’t the large African groups, which SonNo.2 called Wakanda warriors, but the Indonesians with guides chanting like they were rowing Viking ships. We learned to follow the flow and let pass those few people who think they own the place and cut through to kiss the black stone or rub clothes and prayer rugs and tasbih prayer beads against the Kaaba.

I loved doing tawafs alone between midnight and the break of dawn. I’d take it slow, spinning closer to the edge of the court or navigating in the empty pockets that opened in the crowd. I followed the pace of old couples holding hands and fathers carrying small sleeping children and daughters leading fathers that looked like they were taking their last breaths but moved like trains. Normally I’d be jealous of their life energy. It’s not like I’d been clinically depressed. I’ve always been a doer. I’m a writer, a university lecturer, an activist. I picked up gymnastics in my forties. People compliment me on my youthful looks while inside I feel a hundred years old.

In the tawaf, it was fine to pray, contemplate, talk, and observe. My overthinking heart was disabled. I analyzed nothing. I did not narrativize my experiences. My writer’s mind was not operative. My traumas were gone.

The most beautiful tawafs were the ones with my family, like the spontaneous tawaf on the roof under the starry sky. One night, I had a romantic tawaf with Wife. Just the two of us persuading one another we weren’t dreaming. There, I even forgot to desire death, though you are reminded of it after every daily prayer in Al-Haram. Imagine you’re immersed in the prayer. The Qur’anic recitations feel like they are amplified by the acoustics of the sky, like the voice is rising up and raining back down at you. The moment you finish, the imam announces a janaza for those who died in between. They bring in corpses in front of him. Five times a day. Every time you’re thinking, This one’s not for me. Yet. Inshallah, it will be, but my Hajj is not done yet.

Wife said in Mecca it’d be easy to forget to pray for yourself. In the beginning, I hardly prayed for Me. I’d made a list of friends and family. Few of them would expect me to remember them in a place where you forget everything, let alone pray so intensely your beard drips with tears. When you pray for others, God feels like doing you one better, giving you what you ask for others. I prayed for things I believed they needed so desperately. I wanted them to be happy. Once I turned to myself, though my prayers were specific, I was still beating around the bush. My prayers were a tawaf around the thing that was making me cry randomly and shamelessly in weird places. I was looking for a reason to continue living.

My prayers were a tawaf around the thing that was making me cry randomly and shamelessly in weird places. I was looking for a reason to continue living.

We entered the state of ihram for our Hajj before the main event on Mount Arafat and spent the night at Mina, a maze of thousands of white tents, somewhere halfway between the Kaaba and Arafat. It’d served the Prophet as a resting place. For us, it was another test of patience. We didn’t get the tents we were promised, and our beds were made for kids. The air-conditioning was devastating. Bosnians fear the draft like the plague anyway, but this clash of cold AC and hot desert air made everyone sick overnight.

Hajj was all about waiting and moving, waiting and moving. You moved when you waited and waited while moving.

Standing on Arafat is Hajj. Most things can be completed later, but not Arafat. This is why sickness and late buses were nerve-racking. We waited three hours on an overheated bus to get tents. Aida had a fever and was freezing. The tents, which fit hundreds, reminded me of the refugee years, and I thought of the people around the world who’d lived their entire lives in camps, had children and raised them too. The moment you felt something was unbearable, you saw old people with crutches, blind people, and pregnant women. All happy. I’d never seen such patience.

I was at first disappointed our tents were far from the mountaintop, the harsh rock strewn with white-clad pilgrims we knew from romantic-looking photographs, but I realized all places resisted romanticization and was happy to stand in the hot, heavy air facing the rock, praying like your life depended on it. People said it was like waiting for Judgment Day, but I saw sons and daughters with their old parents and couples holding hands everywhere. A man was putting socks on his wife’s feet. The entire women’s tent with broken air-conditioning took care of my daughter. The women had an endless store of painkillers. A young couple from Thailand wanted me to photograph them. I asked them if this was their romantic Hajj. They blushed and turned to Arafat.

Standing on Arafat felt like a frozen tawaf. Arafat was like that circle on the surface of a silent Nordic lake where the pebble hits it and makes ripples that know no east, west, north, or south. Your prayers ripple into the future and deep into the past, retelling your life. But we moved on, close to midnight, to another place that would strip us down, as if we didn’t feel naked already. Muzdalifah was an open field where millions of Hajjis spend a few hours picking forty-nine pebbles for the Jamarat, the Stoning of the Devil. In Sweden, Aida had said a water gun was better for the task, but in Muzdalifah she picked the stones with care.

Hajj makes you feel the earth. In the age of AI, when doomsday clocks are ringing from every nook and cranny, picking forty-nine stones from the dirt of Muzdalifah was the most liberating thing I’d done. I had the desire to ask an AI how it would do Hajj, and what it thinks it would get out of it. I was not just interested in knowledge but genuinely curious. Technological advancement could never cancel out the challenges of Hajj. Even if you arrived on a spaceship, you’d still have to stand with millions on Arafat and pick stones from the gravel of Muzdalifah and throw them at the Jamarat, wait for hours and walk the distances, wear the cumbersome ihram, and circle the Kaaba. As a survivor of genocide and ethnic cleansing, I was a creature of the past, infinitely anxious about the future. It was one thing I knew I was failing at as a Muslim, to trust God when He says we shouldn’t worry about the future but focus on what we do right now. Plant a tree even in the face of the Apocalypse. Pick the stones. Pray. I was a kid again. I wanted to stay in Muzdalifah, but then the sun was coming up and the road to the Jamarat was long.

The Stoning of the Devil takes place over three days. The toughest part was walking in the sun and through a long tunnel with jetlike fans. On the first day, we found an overpriced taxi that dropped us off a mile from the Kaaba. We were nineteen people in a small van. SonNo.1 and I sat in the trunk. Poor people were transported in vehicles for sheep. When the guides told us the animal sacrifice, the qurban, was done, men shaved their heads, except SonNo.1, who only trimmed his long curls and came to be our signpost among a million baldies marching back to Al-Haram for the Hajj tawaf. We went with the flow, smiling, a path opened in the crowd, and we slipped through to the Kaaba and SonNo.1 lifted up Aida so high she reached its Kiswah.

Aida was among the youngest to perform the Hajj. Old enough to understand but young enough to experience it at its purest. She was most inspired by the last ritual, the Sa’y, in honor of Abraham’s second wife, Hagar, whom he left in the desert with their newborn, Ishmael. Our mother Hagar ran seven times between the hills of Saffa and Marwa looking for signs of life. Then the spring of ZamZam burst out of that scorched rock, and because of that well, which quenches the thirst of millions of Hajjis, Hagar founded Mecca. That Mecca is now Masjid Al-Haram, where praying is like praying in space. Outside it is all trade.

For twenty days, I was facing a new kind of sleeplessness. Not just because of the constant traffic of people in the room, the snoring of my roommates, the sickness, and the crazy air-conditioning, but because I feared I might die in my sleep without finishing my Hajj. Like my father in the days before he passed, I’d jerk out of sleep the moment it overtook me, taking a deep breath like I’d been drowning. I remember telling Dad not to fear, that he should go gently into that good night, that it is wise to embrace the close of day. And there I was, gasping for air, coming back from the small death of sleep, to complete the story of Hajj for myself and my children.

Hajj wasn’t a journey to a destination but to the tawaf. It was not about the House of God but the swirl of the people. The Prophet said to Kaaba, “How great are you and how great is your sanctity! Yet, the believer has greater sanctity to Allah than you.” Millions moving in the divine closeness. No petty differences. Men prayed next to women without noticing. The mix of conversations, prayers, and silences, governed by devout patience, became a calming murmur. Even the yelling of the guards and occasional anger by frustrated worshipers were easily absorbed. People accepted responsibility for their actions and their feelings. The desire to answer the call delivered happiness. The straight path from the opening of the Qur’an was not a narrow road but a tawaf around a source with the gravitational pull of a black hole, where knowledge breaks down but love doesn’t cave in. You’re never lost. Wherever you turn there is the face of God.

I’d come to circle around our pretty Swedish lakes after our return, but in my dreams all my tawafs are replayed and waking up is like dreaming. When I feel frustrated as a husband, I try to remember the romantic tawaf with my wife. When I become the old, annoying father, I think of circling with the happy faces of my kids.

They say if you do your Hajj right, and if it is accepted, inshallah, it’s like being reborn.

In the end, they say if you do your Hajj right, and if it is accepted, inshallah, it’s like being reborn. The old me would have doubted the purity of my intentions and the value of my efforts. Now I felt like when my kids were born. That first love. The synchronized crying. The tears that no one questions.

In Mecca, you can cry all you want.

When we finally arrived in the holy city for our Hajj, I thought I had no more tears left in me. Somehow, this year, 1444 Hijri, after years of wait, we were among the millions chanting: Labbayk Allahumma, labbayk. Here I am, my God, here I am.

Stockholm

The photos in Yousef Khanfar’s Hajj project Humanity at Large, in cooperation with the United Nations, are impressionistic images that show human beings as islands within the waves of the great ocean of humanity, intertwined within the same fabric, stitched with fine threads of race, religion, color, and more.