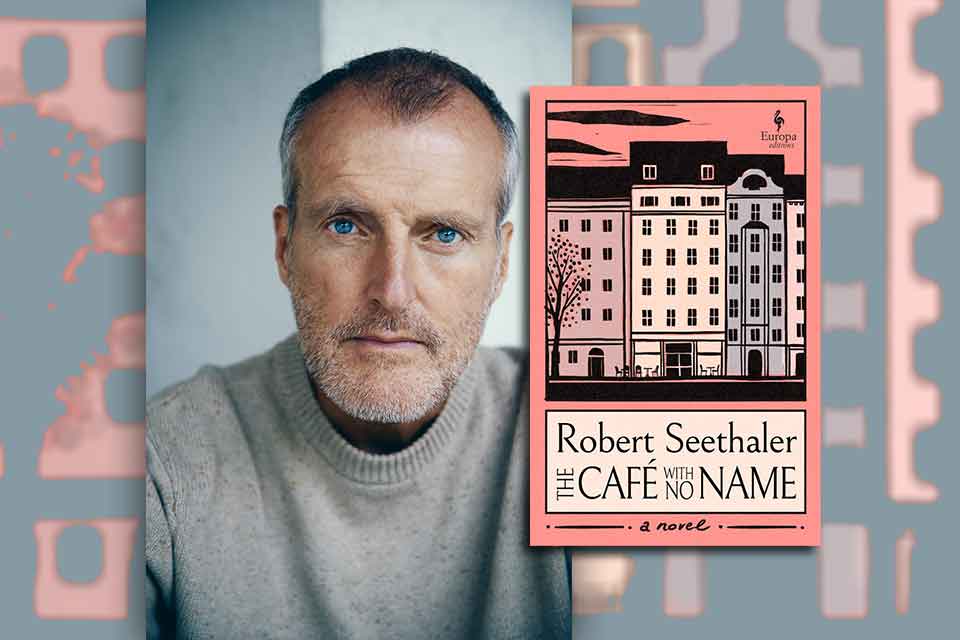

9 Questions for Robert Seethaler

In February, Europa Editions published Katy Derbyshire’s English translation of Robert Seethaler’s eighth novel, The Café with No Name. The novel was a number-one seller in Germany and enjoyed forty weeks on the Spiegel best-seller list. In the novel, a young man raised in a home for war orphans opens a café in the market square of a poor neighborhood in Vienna. The café becomes a place of comfort and congeniality in the neighborhood as modernity encroaches and the city changes.

Q

The Café with No Name is set in Vienna in the 1960s, the place of your birth in 1966. What are your memories of Vienna during this time of postwar rebuilding?

A

I was too young to consciously take in the 1960s. So, it is more of a feeling that I have of them rather than real memories. When I think of myself as a small child, there’s nothing other than great wonder. A strange forlornness. My first tangible images are from the 1970s. The gray winter melancholy in the streets of the working-class district where I grew up. Colorful kites flying in the sky over the Danube. Scuffles in the schoolyard. My father wearing oil-stained overalls. Snow up the sleeves of my jumper, so cold it hurt. The smell of wood and rain. Those kinds of things.

Q

The setting in the novel, the city surrounding the café, is one of encroaching modernity as Vienna recovers from World War II. We see this throughout in details like the ongoing construction, but there’s a point late in the story where the point crystallizes: a character is crying and says that the old Austria is over and though better days will probably come, better days are different days, and that would take some getting used to. So, while the novel is indeed charming and consoling, it’s set within a historical framework that is quite serious. Are characters grappling with these issues in your other work as well, for example in A Whole Life?

A

At some point, every person has to deal with change. Those who refuse are left behind. Robert Simon in The Café with No Name follows his dream to open a café in the poorest part of town. After the trauma of the war and the first years of reconstruction, he wants to create a place where all different kinds of people can come together. The optimistic atmosphere of the postwar period is not explicitly recounted but reverberates in the background, like a stage set dabbed with paint, against which the actual action, the human drama, takes place.

Similarly, in A Whole Life cable-car worker Andreas Egger lives in the most difficult conditions in the mountains while time, almost a century, passes over him. Both men are fighting for their lives, for love and personal advancement. They become acquainted with loss, grief, and death, but despite their limited opportunities, they embrace life as it is. They know there is nothing else.

Q

Florence Noiville, in Le Monde, praised the clarity of your writing and the tenderness. I would like to echo that praise. The writing is direct but with a satisfying style. Here’s a favorite sentence: “Young Robert Simon experienced the end of the war as a choked cheer.” (I realize that translator Katy Derbyshire shares credit for the double alliteration in English.) Who are some writers whose style you admire?

A

In this regard, I am no great admirer. As soon as someone believes they have found their style, there is the great danger of repeating themselves and of becoming boring. I do not rely on notions of style, structure, or dramaturgy. I simply want to tell a story. What counts in writing is the moment. The word. The image. That is all.

Q

You now live in Berlin. Where in Berlin do you find inspiration?

A

It makes no difference whether I am in Berlin or in New York or in a dusty little town on the edge of the desert. Inspiration can be found anywhere, at any time. Everything lights up if you only look closely enough at it.

Everything lights up if you only look closely enough at it.

Q

What do the best novels do?

A

No idea. Do they make you a better person? At least that is what is always claimed. But is that really true? A while ago, at a reading in a prison, I met a convicted murderer who knew the greats of European and American literary history inside out: Faulkner, Baudelaire, Kafka, Dostoevsky, Tolstoy, and so forth. That was before he took a butcher’s knife to his lover and a neighbor. Now he only reads newspapers and the Bible. Of course, he’s an isolated case. And there are certainly examples to the contrary, where a book moves something wonderful in the heart of its readers. I would say that good literature inherently has the potential to release growth. However, it does not guarantee it.

Q

Is there a recent book you’ve read, or a film you’ve seen, that you find yourself recommending to everyone?

A

I just read George Saunders for the first time: A Swim in a Pond in the Rain. He is funny and really understands storytelling. That is interesting for I don’t know so much about that. Otherwise, always and again: Don Quixote, by Miguel de Cervantes. Probably the best novel of all time. But maybe I am just saying that because I am Don Quixote.

I am Don Quixote.

Q

Readers of WLT have a strong interest in translated literature. What other Austrian lit, available in English, do you recommend?

A

I recommend the books by Christoph Ransmayr: The Terrors of Ice and Darkness and Atlas of an Anxious Man. Of course, I am not acquainted with the translations, but Ransmayr can write like few others.

Q

What is reading life like in Berlin? Are brick-and-mortar bookstores thriving? Are translations popular? Do you have influencers, like we do here in the US, who drive selections with their book club picks?

A

I cannot say so much about that. I was never part of a community and generally have no idea about what others are doing. In any case, there are still a lot of small independent bookstores in Berlin. That is bloody good and absolutely right. These booksellers are total enthusiasts and a little crazy. They can barely afford a hot dinner but devote all their energy and creativity to literature and its colorful diversity. And for that you cannot say thank you often enough. And of course, there are also influencers, including the odd bragger. But many do it with great enthusiasm and competence. Real readers, simply.

Q

In a 2016 conversation in the New York Times with Stephen Heyman, something you said stuck with me: “Every life, when you look back on it, reduces itself to a few moments. The moments are what stay with us.” Is there a moment like this from your own life that you would share with us?

A

Hard to say. Every moment has the potential to change a life. Even the smallest scene, the most unlikely moment. A bathroom window that reflects the sun in the face of a hurrying passerby . . . Who knows what then beds down in their subconscious? Nobody can say what remains at the end of a life. There is an image which I keep in mind and want to remember forever: the memory of the small, thin back of my son when he was around four years old. The tenderness and love I connect to it, you don’t forget something like that.

Translation from the German

Robert Seethaler was born in Vienna in 1966 and is the author of eight novels, including the 2017 Man Booker International Prize finalist A Whole Life (2016).