The Roar

Deciding between his mother’s sweet love and his father’s conditional approval, Kimurguk endures a harrowing rite of passage to transform from boy to man.

I must have been fourteen when I first heard it—the roar. Nothing had prepared me for it. Dad returned from a hunt the day before, gave me a pat on the shoulder, and said, “Kimurguk, go as a boy but return as a man.”

Mum feared for me. Her eyes swamped with tears as I left my family to meet the group of Ogiek boys numbered for the rite in the wild. The night before, she crawled up to my bed and whispered, “A mother’s love is sweet like this,” and she shoved a lump of honey in my mouth.

The taste of the honey was still in my mouth the next day when I left home for the rite to begin. I had refused to swallow all of it. I swallowed in trickles as my mouth swamped with sweetness. But although most of it had gone to my stomach, there was a remnant of it in my mouth to last until the razor’s brutal kiss.

As the elder with the blade moved from boy to boy—from groin to groin, leaving in his wake the fall of foreskin, the rush of blood, and the cries of childhood—I shivered as I waited, Mum’s honey dribbling out of the corners of my mouth. When the elder came to me, his face wrinkled with age, his hands wielding the blade, I imagined that his face was my mother’s face and his hands were my mother’s hands.

Those who sat near me would say of it months later, “You smiled as the man cut you. But then you passed out.”

I did pass out, but, unlike some of the boys, I never screamed. The sweetness of honey in my mouth faded, a terrible dryness filled my mouth, and Mum’s face on the elder disappeared. When he opened his mouth to speak, a roar leapt out like a wild animal, and I passed out.

I did pass out, but, unlike some of the boys, I never screamed.

I revived when the elder splashed water on my face. The boys, some of whom—I would hear later—whimpered or sobbed or went all-out screaming, now cheered up and giggled. I must have been thought the weakest of our group, but while some boys keened from the pain in their bleeding crotches, I bore mine, not with fortitude, because I had none. I suspect that the fear of the roar, which only I had heard, had dulled the pain of my bleeding crotch.

“Did you hear that roar?” I asked a boy crouched next to me.

“A roar?” he said with a face that was creased with pain. “No.”

A boy next to him, with a face like an open wound, snapped and said, “There was no roar! We haven’t come to that part yet.”

“What part?” I asked.

“You don’t know?”

“No,” I said.

“Then you know nothing.”

I knew nothing. Dad hid everything from me. Apart from the words, “Kimurguk, go as a boy but return as a man,” he had told me nothing else. As for Mum, it wasn’t her place to share secrets meant for men with boys. I felt angry with Dad. He was always like that. He told nobody what he planned to do. He spoke too little either of himself or of others. The Ogiek people said he was one of the best hunters our people had ever known. They sometimes spoke of my father as if he were a small god among them. They said to me, “Kimurguk, your father could smell the approach of a hyena a mile away.” They also said, “When he shot an arrow, he never missed.” And of his honey-harvesting skills, they said, “He was never afraid of bees, and bees were always in awe of him.” They also said, “Bees knew which smoke was your father’s and which was not, and they obeyed his smoke the most.” I’d also heard people say, “Your father dipped his hand in a beehive and was not stung.”

No wonder they called Dad “The Roar.” I took pride in the name. I was Son of the Roar. Mum was Wife of the Roar, and that was what she told people who were not Ogiek people, who didn’t know my father: strangers, conservationists, tourists, people from the Kenyan government, foresters, and climate-change activists, many of whom had heard of the Ogiek people and the things we do for the Mau Forest, all of which we learned from our ancestors.

It must have surprised Dad, how differently I turned out. I was pathetic at hunting. I tired too easily when I ran. I was afraid of the night. Tree hyraxes scared me. Dad must have been embarrassed that, as the only child of his loins, I had none of his lauded traits. The first time I saw a snake crawl into our hut—I must have been ten at the time—I freaked out and shivered as if I’d seen a ghost.

Dad must have been embarrassed that, as the only child of his loins, I had none of his lauded traits.

“A snake! A snake!” I cried. “Ooo, I’m dead! I’m dead!”

Dad rose calmly from where he crouched skinning an antelope. He came with bare hands and a face as stable as if I’d only told him the sky over the Ogiek people was blue. He turned my arms and looked, scanned my legs, too, and said, “Were you bitten?”

“No,” I cried. “Ooo, I’m dead! A snake! I’m dead!”

“Shut your mouth!” he snapped.

I crashed to the ground, shaking. He threw our door open and walked in. He came out a moment later, dragging the brown snake by its tail, wearing it out as it wiggled its evil head. With his other hand, my father reached close to its head and clenched its neck. He walked to his bag, took out a knife, and sliced off the snake’s head. I fled the scene, screaming. I ran out into the fields looking for Mum and never returned until I found her in the evening, smiling and laughing loudly, posing for white tourists at the mouth of the forest.

* * *

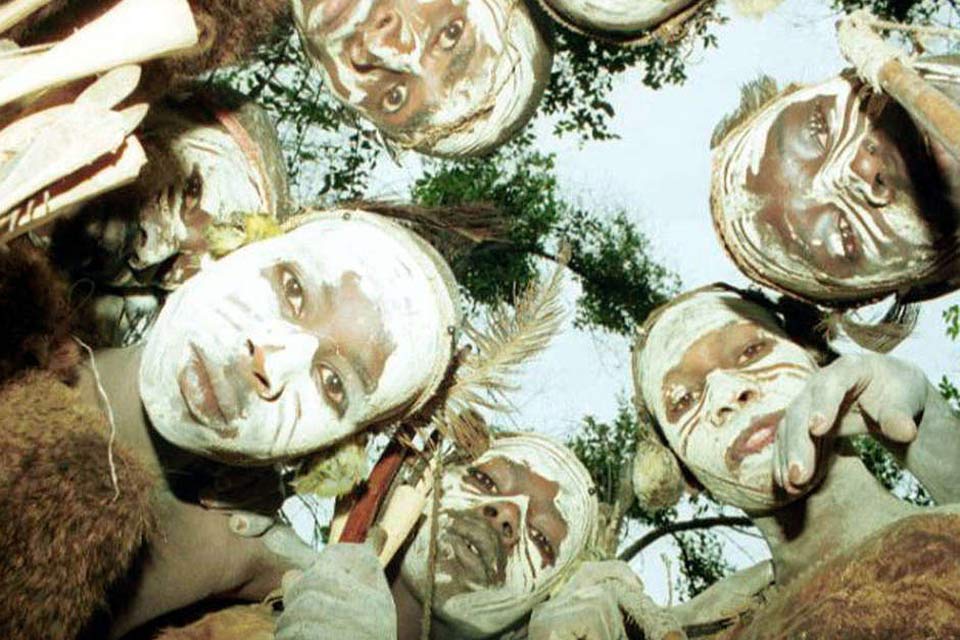

With the ceremonial circumcisions, we began our separation from the rest of our community for a period that I now reckon to have been twelve weeks. It seemed as if I were the only boy in our group who did not know we were going to paint our bodies with clay to resemble creatures of the wild. When my ignorance became exposed, everyone looked at me with surprise, and it was then that one of the boys said, “Kimurguk, are you sure the Roar is your father?”

Everyone looked at me now with probing eyes, even those still smarting from the fresh wounds in their groins. One after another, they nodded in agreement and said, “How could you not know these things when your dad is the Roar?”

“No, he did not tell me,” I said.

“Did you ask?” one of them asked.

“No.”

“Why?”

“My father is always busy,” I said.

“And your mother?”

“Don’t ask about his mother,” another boy snapped. “This is men’s business.”

“But we are not men yet.”

“No, but we will be soon.”

My ignorance notwithstanding, I endured the ordeal of our separation and the pain of my circumcision all in the hope of pleasing Dad, whom I had left as a boy and to whom I must return as a man. I knew all I was as a boy—the names of the beasts Dad hunted from the forest; the rivers that flow for the Ogiek people; all the stories Mum told me; the names of our ancestors, who peep down on us to make sure we are safe while hunting or that we have enough honey to eat, or that we remember the herbs to cure our ailments. I also knew the joys of being known as the Son of the Roar, how, during those earliest of days—before I had begun to turn out badly—my father would hoist me on his shoulders and we would run through the village and into the fields and sometimes into the forest, the wind in my face, leaves crunching underfoot, forest birds chirping. Those were my best days.

I had seen bad days, too. Days I’d fallen ill, and Dad went to the forest for herbs that Mum would boil or mash up for me to chew or drink. There were days when my mother became sick, too. And there were times when I asked what ailed her, and she pulled me to her mouth and whispered, “Your sibling was on its way to us, but a beast came and tore it to pieces.” Then she pressed me into her lean body and sobbed.

And there were days also when my parents quarreled; Dad roared in his fury and his voice shook our hut. Sometimes it was because Mum, in her quest to see more of Kenya, had ventured off the lands of the Ogiek people. I was seven when, during one of my dad’s long absences from home in service to the Ogiek people and traditions, Mum took me on a bus, and all we had was the first Kenyan money I had ever seen—a 100-shilling note—and a card with the name of an NGO woman who had visited our Ogiek community and talked of her dream to emancipate Ogiek women from our primitive ways. Mum had overestimated the value of the money, because we exhausted it before we were halfway to Nairobi, where the NGO was located. So we went from street to street begging for money to go back to Ogiek land. When we returned, Dad, too, had returned, and he nearly ate Mum alive in his rage.

The next time my family almost fell apart was when Mum brought home a book of photographs of Ogiek people that a white photographer had published, and Mum was among his prominent subjects. He had devoted three pages of his book to my mother, and I couldn’t hold my happiness at how comely she was. It was a common saying here that my mother, Wife of the Roar, was the most beautiful Ogiek woman. Tourists readily sought her out and courted her image for their books or films. And my mother was the most generous of women. She gave herself freely to cameras and loved it. She smiled. She laughed. She turned with uncommon grace. Sometimes the tourists gave her money in Kenyan shillings. When a copy of the book of photographs fell into her lap, she burst into tears at the utter beauty of herself and of our Ogiek ways. But Dad was cross with her. When she showed him the pages where she had posed with happy, liberal gestures, my father seized the book and threw it into the fire.

“How could an Ogiek person mingle with people whose ways are at odds with ours?” he roared.

Mum wept bitterly that night and rolled on the floor of our hut, for the book had meant a lot to her. Later that night as I lay sadly beside her, she leaned over to my right ear and whispered, “Kimurguk, one day I will take you out of this place to see more of the world.”

I remembered those bitter days of boyhood. But what did I know about manhood?

* * *

I endured the pain of my circumcision with companions, most of whom limped or walked with legs curved outward, like gorillas. Every now and again, one of us gave a cry, pinching the skin around our crotches. But we learned to bear the pain like men. My friends shared stories of the misfortune of boys who came here just as we did but could not come out as men: boys who died from the blade, boys whose blood ran and never stopped, boys whose wounds got bad and they got fevers and spasms and died. These stories sent shivers through me, but we soon distracted ourselves with body painting.

We painted our bodies with white clay. I loved the transformation of our faces into bestial aspects. We grinned and popped out our eyes. We barked. We hooted. We roared. We chirped. We played all the wild beasts we could think of. We wore animal skins and stuck bird feathers in our hair. Scary yet benign, we braced ourselves for the night.

My closest companions knew about the nightly ritual. Again, they were disappointed that I, the Son of the Roar, had no idea of the ritual.

“My dad did not tell me,” I said.

“Maybe he did it on purpose,” one said.

“Or he didn’t want to ruin it for you,” another said.

“Yes,” another agreed. “I hate it when someone tells me how a story is going to end before even telling the story.”

“I like to know the end of a story from its beginning,” another boy said.

“Nonsense. That’s like dying before one is even born.”

“I don’t like stories.”

“I think you haven’t heard good Ogiek storytellers.”

“Like my father.”

“Like my father, too.”

“Oh, my mother is the best Ogiek storyteller alive.”

“That’s not true,” I said. “My own mother tells the best stories.”

The boys giggled, and one of them waddled around and said, “No, your mother takes the best photographs for tourists.”

The rest of the boys paused their laughter and waited as people do for thunder after a blaze of lightning.

I said nothing. I did nothing. It was no news that my mother posed for tourists and that some Ogiek people, such as Dad, did not like the ways of tourists. They didn’t like foreigners who brought money and flashed camera lights as if we Ogiek people were in a darkness out of which they came to deliver us. But Mum had a reputation for mingling with such outsiders.

“You haven’t heard my mother’s stories,” I said finally. “They are as beautiful as her face and splendid as her photographs.”

The boys chewed over my words and nodded. One after another, they waddled to me and said, “I saw her picture in that book.”

“I saw it too.”

“Me too.”

“I saw it too.”

“I heard the tourist brought three copies of that book in Ogiek land.”

“No, four.”

“Five.”

“No, seven.”

“No, three.”

We disputed the number until an elder intruded on us and hushed us with a yelp.

* * *

Night came and peered over the Mau Forest and the rivers. A handful of stars came out. The wild awoke with a chorus of nocturnal noises. I was familiar with their noises. I had heard them all from my parents’ huts and during the nights when my family sat outside and Dad ate his supper or Mum told a story she had heard her own mother tell.

But here in the wild, the air seemed to await something unknown. I felt in my blood a secret of the night that I had no words to describe. My close companions whispered of it, scraps of what their parents, elder siblings, or secret chaperones had divulged to them of the mystery of the night.

“The cry of a beast,” someone whispered to me.

“A roar of a monster,” another said.

“Have you heard it before?” I asked.

“No,” they said. “Have you?”

“No,” I said.

“But you should know.”

“My elder brother told me of the roar.”

“And the roar.”

Giggles broke out among them and soon gave way to tense expectation.

When I first heard it, it seemed as if my blood turned cold. A sudden shudder ran through me. Goose bumps covered my body. I shivered as if I had come down with malaria. Some of my companions cowered and whimpered, especially boys my age or slightly younger. But even the oldest of us seemed to cringe at the noise. It was an eerie noise, sinister and cruel, as if out of the throat of a beast never seen in physical form in Ogiek forests or fields, a beast with a toothy scowl, paws spread out, and fur dripping with the blood of prey.

In a way, the noise called to my deepest fears, worse than the fears I had when a snake crawled into our hut and I cried out to Dad. It was the fear of being cut off from Dad and his legend, of being cut off from the love of my mother, or being cut out of the precious lands of the Ogiek people. It was the fear of death in all its forms and manifestations. It was the fear of life and its contradictions. It was the fear of coming back to Dad as a boy, of meeting my family broken apart, of my ancestors spitting in utter rejection of me. It was all these, and still more.

The roar! The roar! There was something familiar about it that I could not name. And yet it was strange and unfamiliar in the starkest way.

It haunted us in the wild like a resident ghost on whose turf we had encroached. Would it pounce on us? Would it eat us? Would it spare us? Would it bide its time and come another night? It hounded us and terrified us. Some of us cried. Tears dribbled down my cheeks in the cold night.

Night after night the roar came. For weeks in the wild, the roar lived with us. Or it came like an order of nature and thinned out into silence in the middle of the night.

As weeks passed, we absorbed the secret words of the roar. It was a secret language, and only those who would be men could understand it. In the roar, I heard Dad and all his legend. I heard my mum, saw her beauty and all her sorrows. And then I saw myself apart from them, walking into a forest that was my own destiny.

In the roar, I heard Dad and all his legend. I heard my mum, saw her beauty and all her sorrows.

As we, the young initiates, became more familiar with the roar, we knew our time of separation would soon be over. We were certain of its end when the elders of our people exposed to us the secret instrument of the roar.

There it was—an animal horn with a furry, leathery affair around it—in the hands of Dad. I could not hide my pride and joy. The boys, now men, yelled in praise of him. “The Roar! The Roar!” they called. I lent my voice to their call as Dad smiled, raising the horn aloft.

* * *

I had left home as a boy but now returned as a man to my mother, who hurriedly took my hand and said, “This is our chance to go to Nairobi, my son. I got more money now from tourists. This won’t be like last time. Let’s go, Kimurguk. Let’s go. This place is not big enough. There is a lot outside this forest. Come with me.”

“No, Mum,” I said flatly. “I’ll stay here.”

“You can’t stay here. Come.”

“No.”

“Come.”

“What of Dad?”

There was a flash of fear in her eyes, and I turned to see my father standing behind me, hoisting a dead antelope. He dropped the game, cleaned his bloodied hand with dry leaves, and said, “You can follow her if you want.”

“No,” I said. “I’m staying here. I’m an Ogiek man now.”

Dad didn’t look impressed. Or he was, but he wasn’t a man who showed his emotions openly. He walked quietly into his hut.

Mum took a bag and hurried out. She shot me two teary looks in case I changed my mind. I looked away and she ran far out into the fields, her tall, beauteous figure shrinking in the distance until she was gone.

I never saw her again.

Dad and I never talked about this. Whenever I brought up her name, he cut me short with a roar.

We didn’t talk very much, not even when we went hunting together. He was more action than words, more a roar than eloquence. And then one day, Dad took his hunting weapons and went to the forest without me. He never returned.

Our Ogiek people say they knew he would go like that—just as some of his ancestors did. They went to the forest and from there crossed into the world of ancestors. But some say he was mauled by a wild beast. Some even say he left Ogiek land to look for his wife. Some others say they saw a man who looked just like Dad in Nairobi. Someone spoke of a lookalike of Dad’s who worked at the Masai Mara National Reserve. And there were people who claimed to have caught a glimpse of Dad in our forest, but as soon as they ran to meet him, he was gone.

As for Mum, I heard nothing from her and nothing about her. I sometimes wonder if she became happy after leaving us. Our Ogiek people still remember her and her lovely photographs. I remember the happiness she brought to tourists and strangers. I remember our failed road trip to Nairobi. But my best memory of her is of that night before my puberty rite, when she shoved a lump of honey in my mouth and said, “A mother’s love is sweet like this.”

Devon, UK