Editor’s Note

Given the multispecies theme of this issue’s Delhi cover feature, I got to wondering: How often do plants and animals appear in WLT? In the following pages, attentive readers might catalog Marie Lundquist’s “buttercup-guilt”; Agur Schiff’s little goldfish; the tomatoes, grasshoppers, and maples in Ken Hada’s poetry booklist; the cranes of Tashkent; Gabriela Cabezón Cámara’s Chaco forest; Katie Goh’s oranges; Ravi Agarwal’s vultures; Vandana Singh’s and Sumana Roy’s pipal trees (asvattha); Nitoo Das’s and Prateek Vats’s rhesus macaques; Siddhartha Deb’s warrior monkey-god, Hanuman; and Manjula Padmanabhan’s tendrils. The longer you look, the more the menagerie grows.

Given the multispecies theme of this issue’s Delhi cover feature, I got to wondering: How often do plants and animals appear in WLT? In the following pages, attentive readers might catalog Marie Lundquist’s “buttercup-guilt”; Agur Schiff’s little goldfish; the tomatoes, grasshoppers, and maples in Ken Hada’s poetry booklist; the cranes of Tashkent; Gabriela Cabezón Cámara’s Chaco forest; Katie Goh’s oranges; Ravi Agarwal’s vultures; Vandana Singh’s and Sumana Roy’s pipal trees (asvattha); Nitoo Das’s and Prateek Vats’s rhesus macaques; Siddhartha Deb’s warrior monkey-god, Hanuman; and Manjula Padmanabhan’s tendrils. The longer you look, the more the menagerie grows.

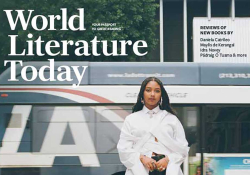

Nature continually makes its presence felt even in a megacity the size of Delhi, with an estimated human population of eleven million in the city proper. While working with illustrator Emily Holson to conceptualize this issue’s cover art, we shared with her guest editor Amit Baishya’s introductory note, in which he discusses Nilanjana Roy’s novelistic use of cats as narrators. “Cats are ubiquitous presences in the dargah and a sacralized animal in Islamic tradition,” Baishya writes. “While Roy’s duology is an elegy for disappearing Islamic and Sufi-influenced practices and traditions in Delhi, it simultaneously depicts the impact of neoliberal processes on feline habitations. Older constructions with sloping roofs where cats used to wander make way for high-rises and gated communities in the current day.” Added at a late stage in the illustration process, the cat on the issue’s cover is a nod to the ubiquity of Delhi’s fauna.

Turning to the Swedish landscape of Marie Lundquist’s prose poems, another sort of nature leaps off the page. One poem mentions “fernlike stains” and “winter apples.” Another poem begins with a metaphor about pruning, then segues into an image of death staking her tent “down into flesh.” The pruning/piercing image returns in “branches sharpened into arrows or pens,” this time as a metaphor for writing. Here’s a third poem in its entirety:

Every time we lay claim to something, we fall into the yarns of loss. Don’t let the pretense of ownership run away with you. Weak parts, like arms and legs, can so easily disappear. It just takes the heart rising out of the ribcage for death to open her only wing and sweep it toward her.

Death here, birdlike, seemingly wants to incubate but inevitably preys upon the heart. It’s a startling, chilling image. In English, Lundquist’s verse collections have such titles as I walk around gathering up my garden for the night and The garden of the dead. Lundquist’s translator, Miriam Åkervall, tells me that the Swedish title of the latter book, Astrakanerna, refers to a common variety of domestic apple, similar to a crab apple. “It’s a word that carries a lot of cultural nostalgia,” Åkervall writes.

In The Sixth Extinction and H Is for Hope, Elizabeth Kolbert synthesizes the work of thousands of scientists who keep warning us that species loss will be (already is) one of the great catastrophes of the climate crisis. Writers and artists may not be able to depict the staggering scale of such spoliation in their work, but they can begin to articulate the solastalgia, or grief, that attends such loss. In striving to represent the multiverse of species in the ecosystems and bioregions we all inhabit, they help us look and empathize, through text and image, beyond ourselves.

Daniel Simon