Opening a Path to My House in Palestine: A Conversation with Palestine Prize Laureate Ibrahim Nasrallah

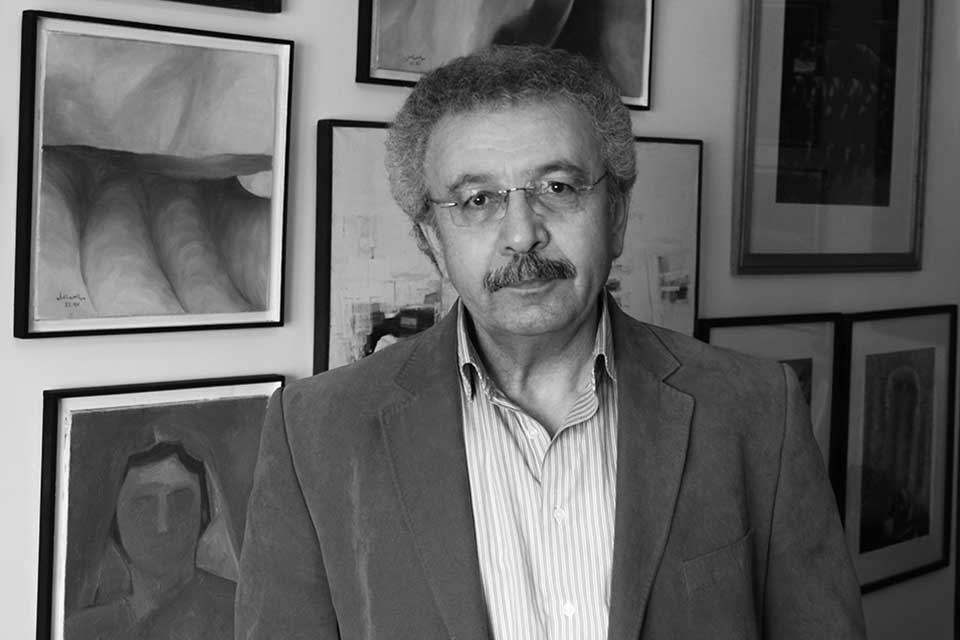

Writer, artist, and photographer Ibrahim Nasrallah was born in 1954 to Palestinian parents who were uprooted from their land in 1948. The author of fourteen poetry collections and twenty-four novels, his novel Prairies of Fever was listed by The Guardian as one of the ten most important novels written about the Arab world. Among many other prizes for his work, he has been honored with the Jerusalem Award for Culture and Creativity (2012), the Booker Prize for the Arabic novel (2018), and the Palestine Prize (2022). His works have been translated into a number of languages. He recently spoke with Shereen Malherbe about his life and work as Palestinians marked the seventy-fifth anniversary of the Nakba.

Writer, artist, and photographer Ibrahim Nasrallah was born in 1954 to Palestinian parents who were uprooted from their land in 1948. The author of fourteen poetry collections and twenty-four novels, his novel Prairies of Fever was listed by The Guardian as one of the ten most important novels written about the Arab world. Among many other prizes for his work, he has been honored with the Jerusalem Award for Culture and Creativity (2012), the Booker Prize for the Arabic novel (2018), and the Palestine Prize (2022). His works have been translated into a number of languages. He recently spoke with Shereen Malherbe about his life and work as Palestinians marked the seventy-fifth anniversary of the Nakba.

Shereen Malherbe: Congratulations on being recognized for your contribution to Palestinian literature by winning the Palestine Prize! It is an honor to be able to interview you and to be able to ask you to share the inner workings of your writing career and journey to becoming one of the most renowned Palestinian writers of our generation.

Ibrahim Nasrallah: Thank you for your kind words; I am honored to have received the Palestine Prize award along with many prestigious Palestinian achievers in literature, art, and science.

Malherbe: The Palestine Prize Foundation’s mission is “To preserve, protect, and promote Palestinian dreams and achievements.” How do you feel about being recognized as the Palestine Prize laureate for literature in 2022?

Nasrallah: I am privileged to be the second writer in the field of literature after the renowned poet, critic, and translator Dr. Salma Khadra Jayyusi. Also, because this specific award comes from an independent institution bearing the name Palestine, which is important to me. It is managed by a team of high-caliber professionals from around the world, who select the laureate according to a high standard of criteria similar to what you would expect from prestigious international awards.

Malherbe: How important is literature in terms of capturing Palestine’s past, present, and future?

Nasrallah: For Palestinians, literature is part of their act of existence; existence in beauty, in being able to love this world we live in, and in standing up for its people. It is part of the Palestinian endeavor to partake in the world’s literary and human-created beauty. It is, in a way, us Palestinians saying thank you to each culture and writer who offered us the joy of reading good books, books that enriched our souls with hopes, ideas, and artistic achievements. I think we write because we really love the world, and because we are faithful to the world’s great values.

On the national level, I believe that both Palestinian literature and art were and continue to be responsible for reshaping the Palestinian identity after the Nakba in 1948. For Palestinians, their literature is another holy book along with other holy books they believe in. Their literature was able to transport the Palestinian people from despair to hope and from loss to action. Although modern Palestinian literature was born in restraint, it embraced freedom and defended it.

I recall that, back in the 1970s, one of my first poems was dedicated to Stephen Biko, the South African anti-apartheid activist who was killed in detention. And my first novel was a saga of empathy with the Saudi people, whom I lived with, after witnessing the challenging life they lived in Saudi Arabia. Although an oil-rich country then, its people were suffering from severe poverty and life-threatening diseases like malaria and tuberculosis. My point is that my own experience shows that I wrote about the suffering of other people before I wrote about my own! I think that true empathy can be realized only if one is able to see the sufferings of others through the lenses of one’s own suffering, or else one’s suffering is deemed blind.

True empathy can be realized only if one is able to see the sufferings of others through the lenses of one’s own suffering, or else one’s suffering is deemed blind.

Malherbe: And what about the past, present, and future of Palestine?

Nasrallah: The core Palestinian issue is a struggle between existence and erasure. There are those who want to deny the Palestinians their existence by expelling them from their homeland; during and in the aftermath of the Nakba, more than five hundred Palestinian towns and villages were erased, and I mean actually and completely erased from the map. New parks, commercial centers, and parking lots were built on these lands. Erasure impacted the Palestinian names: names of lands, villages, cities, archaeological sites, etc., and these places were given new names! Erasure is responsible for denying the Palestinian the right to the house in which he/she was born, and in which this Palestinian’s grandfather, father, and his/her entire family were born and lived for generations! Indeed, there are attempts to erase the Palestinian’s memory of his/her homeland as well as the memory of his/her children!

The six million Palestinians in exile did not fall from the sky! They were on the land—their land—but were forced to wander in other lands as strangers in refugee camps. It is a story that has been going on for seventy-five years, and our literature is concerned with this past and with this present, a present that is becoming more aggressive by the day; a present where occupation forces kill our children every morning; an occupation that the United Nations describes as an apartheid regime.

As a writer, with your literary texts you defend and depict the past, present, and future, even if you are writing a romance. This is what I did in my last novel, which is based on my autobiography. It is a love story about love in exile, but at the same time it is about the past that my mother lived, the present that I live, and the future my children and grandchildren will live in.

Palestinian writers are trapped in a besieged existence, and we have to say out loud using all means available that we are alive, that we are beautiful, that we love life, and that we do not stand with Palestine because we are Palestinians but because it is a daily test for the conscience of the world. Our writing is all of this, and it is also our attempt to establish a living memory, to rebuild the past life so generations who did not have the opportunity to live that past can live it. Above all, our writing is intended for us to own our stories, because if we do not write our story, it becomes the property of our enemies.

Our writing is intended for us to own our stories, because if we do not write our story, it becomes the property of our enemies.

Malherbe: You were previously a journalist. Why did you choose novels and poetry as your medium of choice over other forms of writing?

Nasrallah: Prior to working in journalism, I was a schoolteacher and worked for two years in a desert area in Saudi Arabia. This was one of the hardest experiences in my life—I had to go there because there were no jobs in Jordan where I lived, and I had to start earning a living to support myself and my family, who were living in poverty in a Palestinian refugee camp. It was a remote desert place where there was nothing. There were no streets, no electricity, and not even a school building for the school I was teaching at. I almost died due to a malaria infection, which took the lives of many of my young students and fellow teachers, by the way. It was after this that I realized this banishment was intolerable. I decided the priority in my life should be my writing, so after two years I returned to Amman. At that time I did not have the luxury of choosing and could not find a teaching job, so I accepted what I was offered: a job in journalism. For the next eighteen years I continued working as a journalist, but for me that was just a career; my main devotion remained to literature.

In fact, choosing writing as a life path was not a decision that I took at a specific point. I started writing when I was fourteen years old. I wrote poetry and novels and never stopped. In my teens I had a dream of learning music and playing an instrument, but this was unachievable given my family poverty, so I continued to write. I also painted and became a photographer and had four photographic exhibitions. I wrote songs and composed music for a few songs and wrote two books of film criticism. I have a great passion for all kinds of art. I consider different fields of art to be tributaries to my literary writing. Nevertheless, writing poetry and novels remained the central project in my life, and for its sake I made many sacrifices.

Malherbe: You have created fourteen poetry collections and twenty-four novels, including your project of eight novels covering 250 years of modern Palestinian history. What motivates you to continually create literature?

Nasrallah: I think the power of life in me is the main drive for my writing—perhaps it is my embrace of life and my insistence to live life as one should. In each moment of my life, I was, in one way or another, fighting some sort of death whether it was a personal death or the death of my people. Wherever I passed or stayed, I do not want it to be said that Ibrahim died here; I want it to be said that Ibrahim lived here! And what better proof of me living than my own writing? I realized that this is what I can do, and I also realized that it is not enough for it to be said that he lived “here”; I want it to be said that he lived “there.” There in the homeland he did not see, in places his parents were expelled from, and in times when he was not yet born.

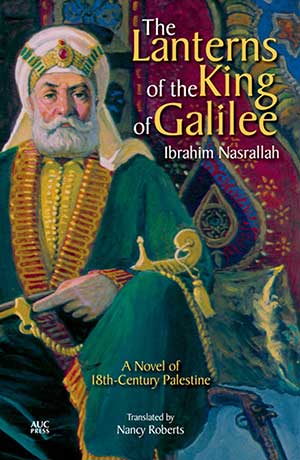

While writing my book Lanterns of the King of Galilee, a novel that recounts historical events which happened in Palestine in the eighteenth century, I felt that I lived there. I could swear that I lived there and that the eighty-five years narrated in the book are years I lived. I was fifty-seven years old when I finished writing the book, but I had lived for 139 years. I truly, wholeheartedly lived the life people lived at that time in the area between Tiberias and the Sea of Acre. This happened with me in every novel and every poetry collection I wrote, so I can confidently tell you that I am now more than one thousand years old!

While writing my book Lanterns of the King of Galilee, a novel that recounts historical events which happened in Palestine in the eighteenth century, I felt that I lived there. I could swear that I lived there and that the eighty-five years narrated in the book are years I lived. I was fifty-seven years old when I finished writing the book, but I had lived for 139 years. I truly, wholeheartedly lived the life people lived at that time in the area between Tiberias and the Sea of Acre. This happened with me in every novel and every poetry collection I wrote, so I can confidently tell you that I am now more than one thousand years old!

I believe that for many writers, the main drive for writing is for the writer to remain vigilant and amazed, not to age in his views toward the world, life, freedom, and literature. To that end, I purposely choose the title of my latest novel/biography to be My Childhood So Far. In a way this book transcends the moment of its birth to the past and the future. For me, any creative writing has its own logic that goes beyond the moment the text is born; it is somehow like a time machine—while putting your thoughts on paper you will go back to the past to search for the roots of these thoughts and feelings, and then you return from the past and go forward to the future trying to figure out how things will turn out. In this book, both the past and the future are Palestine. Palestine has suffered from many epidemics, unfortunately, and it is no coincidence that the Covid epidemic is the thread that connects the events of the novel from start to finish.

It is critical that intellectuals speak out—this is a constant test of our vigilance, of our consciousness, and our conscience.

What is happening in the world, what is happening to Palestinians, is a test of our writing. Writing in this sense is an attempt to say something so it will not be said years later, quoting the great German writer Bertolt Brecht, “why poets, writers, and artists kept silent.” It is critical that intellectuals speak out—this is a constant test of our vigilance, of our consciousness, and our conscience. Writing becomes the writer’s attempt to say, while contemplating human existence through the characters of his novels and through his poems: I am human.

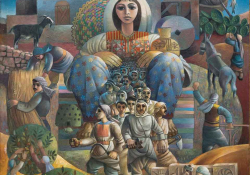

Moreover, I feel that my responsibility in writing is not only toward humans but also toward our planet, the only place we have as humans to live on! I have been asked repeatedly why animals are present as key characters in all my works. There are horses, birds, wolves, dogs, and many other creatures. I reply by saying, just imagine if these beings suddenly disappear from earth, would we humans continue to exist? I do not think so.

Although I am preoccupied with writing about my people and our cause, I also stand strong in defending this world. It is my world, and both Palestine and the world are of the same importance to me. I always feel rage when I hear about Israel’s atrocities against olive trees in Palestine. Some weeks ago, a farmer from Burin, a village near Nablus, confirmed to me that the Israeli soldiers have destroyed and burned 16,000 olive trees in his village in 2022. In total, during the past twenty-three years, Israeli forces destroyed 2,750,000 trees planted by Palestinians in the occupied territories.

Malherbe: How has your style changed throughout the years?

Nasrallah: Each time in our lives has its own questions, its own consciousness, and its own meanings. The life we live and the questions we have when we are in our twenties are different than those we have when we are in our thirties or forties or sixties. Meanings change over time, like the meaning of life and death, and many of our thoughts are changing constantly and sometimes drastically. It is true that humanity’s core values remain unchanged, but one’s questions about these values evolve with time to be more profound. I would say this is a general trend for all people, but for writers there are other evolutions that affect writing’s methodology and techniques. A writer’s experience and cultural background and even issues he writes about necessitate the development of new writing styles and techniques to better fit the evolving topics. Such development would not be possible if the writer did not engage with other creative mediums such as cinema, theater, drawing, and photography.

In my experience, in the field of poetry my writing varied from the poem of normal length, to the very short poem, to the epic poem. Even the poem that forms a complete book and is based upon a technique depicting narration in a biography, a history book, or arts like my latest opera-like poetry collection, Love Is Evil. All of these types of poetry writing are different.

Likewise, and because my novels explore different topics, I wrote the postmodern psychological novel, the historical novel, the social, the exotic, and the science fiction novel. I had to be innovative in technique. I like this challenge; I like the book that challenges you to create new styles, to tap an undiscovered area in your mind, to be able to develop as a human being! This capacity to be innovative and to diversify the writing experience was my intention in both my projects The Palestinian Comedy and The Balconies. Each project consists of several novels, and each novel is unique in its artistic style, characters, time, and place, and the reader can read any book without having to read the rest of the series. For me this approach allowed me to be creative without following a set mold of writing novels in a trilogy or quartet.

Malherbe: Could you tell us about the technical challenges you face in creating a new piece of literature?

Nasrallah: Each time there are different challenges, because every literary work is a world of its own, like how planets vary! To continue with that metaphor, it is true that we travel to all planets by spaceship, but each journey needs a specially made spaceship tailored to accommodate the distance, the environment in our destination, and our objective for the journey.

For me, I start my writing journey by writing new ideas that occur to me on paper. This results in having several files for several new books active at the same time. I am always thinking of these fetal ideas, and whenever a new development arises for one of these novels, I add it to the file. I feel that I have a bank of ideas, characters, and events; for me the time between the first spark and writing the book was never less than five years.

The most difficult step in the whole process is writing the first sentence of the new book; it’s a real terror! I always try to escape this moment, but once I start, I never stop. I have never had writer’s block, and I think this is because I don’t stray from writing once I start. I write on a daily basis without taking a weekend break or any other engagements during the day. I write only in daytime, never at night, and continue this way until I finish the book. The only luxury I allow myself during writing is watching a different movie each night from American and world cinema.

Malherbe: How has your own experience of exile and belonging impacted you and your work?

You have to be loyal to your exile as much as you are loyal to your homeland.

Nasrallah: It has, indeed, shaped my life and my experience. Living in exile means that you are present against your will in the place where you should not be. However, you refuse to be merely a person passing through life and passing through place without leaving an imprint. You are not a cargo crossing borders. You refuse to be dependent. You must build yourself and want to contribute in building your exile. Let me say: you have to be loyal to your exile as much as you are loyal to your homeland. It is not surprising that my fictional project was divided into two halves, one half focusing on life in exile that includes ten novels (The Balconies), and the other half focusing on Palestine that includes fourteen novels (The Palestinian Comedy). The same applies to my poems—as I pointed out, you cannot be interested in only one part of this world, even if that part is your homeland.

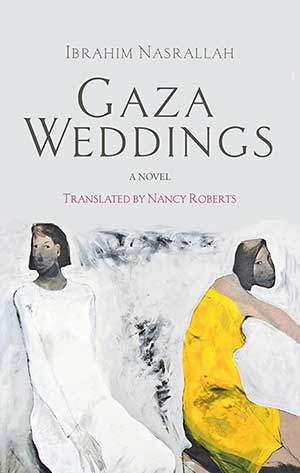

There is a wonderful Palestinian folktale that I wrote about in my novel Gaza Weddings. It states: “Man was created from two soils; the dust of the place where he was born, and the dust of the place where he will die.” Personally, I know the dust on which I was born, and I will always stand strong in defending it, but I will also defend every other soil in the world, for any of it could be the dust on which I will die.

There is a wonderful Palestinian folktale that I wrote about in my novel Gaza Weddings. It states: “Man was created from two soils; the dust of the place where he was born, and the dust of the place where he will die.” Personally, I know the dust on which I was born, and I will always stand strong in defending it, but I will also defend every other soil in the world, for any of it could be the dust on which I will die.

Malherbe: You mentioned in the foreword of Time of White Horses that you have collected many firsthand accounts of Palestinians’ stories “over the course of twenty years.” How have they impacted or shaped you as a person and your work?

Nasrallah: The novel was published in 2007, after twenty-two years of hard work and preparation since I began collecting oral testimonies in 1985. The importance of these testimonies is that they represent the lives people lived in the past—it reconstructs social structures and human interactions, and retells the small details of the daily life that a writer never lived. Thereafter, as a writer you create your own setting, characters, and events. Also, as a writer you have to be a master of all trades; you have to be a historian to create history, an engineer to create cities, a psychologist to understand people, a farmer who knows farming, a military expert, an educator, a trade unionist, and an anthropologist! In preparation for Time of White Horses, I read almost everything about Palestinian heritage and folk stories. While writing, some books necessitate an in-depth study of certain topics. You will find that you need to establish a library for these novels, and this really happened with me in many cases, while for other books you are the library you need, meaning that your own experience and knowledge and understanding of this world are the background you need to write.

Malherbe: Can you tell us about your latest novel, My Childhood So Far?

Nasrallah: It is a novel based to a great extent on my autobiography. The book covers almost sixty years, post-Nakba, in the Wehdat Refugee Camp near Amman where I lived. It is about “the fantasy that I lived, and the truth that lived me,” as I wrote in its introduction. It is a journey within myself that allowed me to know how much I have lived, and the level of life in my soul; this discovery was to me one of the pleasures of writing this book. After finishing this novel, I found out that it is essentially a love story. I always wanted to write a love story that transcends war and life’s vicissitudes, and it happened that I wrote it unintentionally! It is great to long for something for your entire life, only to discover that you have actually lived it; this really happened to me in this book. This novel is not a bleak Palestinian story—there is a lot of irony and cheerful events. It could be said that it is a novel about life, not death.

Malherbe: It is your biography in a novel; why did you write it like that? Why didn’t you write a traditional biography?

Nasrallah: This novel is my story as much as it is the stories of others who shaped my life, and I have in return shaped their lives. It is my journey in time, past and present, and at the end of the journey I concluded that it would be a blessing if one finds out that one’s lived life is more beautiful than any novel they read or wrote! This is true especially for writers: if you are living a poor life intellectually and humanly, you will achieve nothing, no matter how many books you write. I believe any person is victorious only if this person succeeds to live life as life should be lived; one would be lucky if this person was able in his or her lifetime to manifest what the great poet Pablo Neruda concluded when he titled his memoirs Confieso que he vivido (I confess that I have lived). This would be the utmost fulfillment of one’s human condition, with that life being the best book one could write or read!

In My Childhood So Far, I embraced the novel’s logic, not the biography’s, because the first gave me the ability to dissolve the egotism in the “I,” the main character, so it won’t be the only focus of events. Unlike other biographies, I deliberately sought to dismantle and dissolve egotism, and I stripped the “I” from its vanity of being the one and only hero in the book. From start to end, I wanted to bring onboard in this journey all those who contributed to shaping my life. I wanted to say clearly that life was not mine alone, and I like to think that I was able to achieve this with the power of love. This could not have happened without using the novel model, a much more democratic kind of literary style than the biography (except maybe for a few examples, which is more like a dictatorship where the one and only leader occupies the scene). My objective was to say a big thank you to my family, friends, and loved ones for enriching my life. I believe my objective was achieved; they realize that their presence in the past has led us to this great point in the present and to the better future we look forward to, and that their presence was and continues to be the best, most beautiful thing that happened to me.

Malherbe: Do you have any advice for Palestinian writers who want to make an impact through their literature or art?

Nasrallah: Advising others is complex! There is abundant advice and commandments in books, including holy books, put forward by prophets, philosophers, writers, mothers, and fathers. Yet mankind still commits the most heinous acts, including killing, wars, enslaving other humans, and controlling others’ lives. Therefore, I am reluctant to give advice, but I can share some thoughts on writing from my own experience. For example, I believe that writing about a great cause needs a very high-level writing approach and techniques to be able to present one’s cause sincerely. I also believe that the writer should write with all his or her heart, so readers will read your work with all their hearts—if you write with half of your heart, people will read you with half of their hearts. And if you write with a quarter of your heart, people will read you with only one-quarter of their hearts!

Malherbe: How do you feel about the necessity of diversity in Palestinian writing, both for the writers and readers of Palestinian literature?

I believe diversity is a sacred idea, whether we are talking about the world in general or the world of literature.

Nasrallah: I believe diversity is a sacred idea, whether we are talking about the world in general or the world of literature, or the literary and artistic world of a certain writer or artist. Personally, I do not like the idea of templates, or constancy, because that means stiffness, which becomes even worse whenever the writer produces more similar works. Diversity in literature comes from the capacity of each individual writer to present his own experience in the most appropriate style for this specific experience. Diversity is inevitable for Palestinian literature due to the differences in conditions and even in geography where Palestinians live; a Palestinian writer living in Haifa and Nazareth differs from another writer living in Ramallah, or in a Palestinian refugee camp in Lebanon, or from a writer living in Amman, like me, or one living in Paris, New York, or Bogotá.

Malherbe: Have you faced any obstacles in your writing career that you would like to share?

Nasrallah: I faced many challenges. To start with, it was not possible for me to go to college. I had to educate myself and work on my own, to learn and to absorb the most prominent literature and art produced by the world. Also, at the beginning, I was a young writer at a time when there was a cultural scene packed with great Palestinian writers, and I had to make my way and stand out among the big names. Later, because of my writings, I was subject to many violations by the authorities. My books were confiscated and banned several times. Literary events I participated in were also banned, and I was banned from traveling abroad for six years! In 2006 I faced a serious threat of imprisonment when the authorities referred me to court with serious charges because of a poetry collection I had published. Had it not been for the great support by writers, journalists, and academics in Jordan and Arab countries and from all around the world, I would have been sentenced and sent to prison. That campaign convinced the authorities to drop the charges. However, on the literary level, I think the constant challenge for every writer is to continue being innovative, to create new works capable of surviving over time, and the constant development of the reader’s taste.

Malherbe: What do you feel is your greatest personal achievement?

Nasrallah: It brings me great happiness that most of my readership is young men and women. This is a fact I have witnessed many times, despite what is commonly said—that young people are not interested in reading anymore!

Malherbe: If your writing could achieve or change anything, what would you want that to be?

Nasrallah: My hope is that my writing could contribute to opening a path to my house in Palestine, to facilitate my return, even if this contribution is no more than the distance of one meter in a long path. I also hope that my writing finds a space, no matter how small, in the heart of the world.

April 2023

Translation from the Arabic

Visit worldlit.org to read Nasrallah’s poem “Late Olives” and Malherbe’s story “The Cypress Tree,” which appear in the Summer 2021 “Palestine Voices” issue of WLT. To learn more about the Palestine Prize, visit www.thepalestineprize.org.