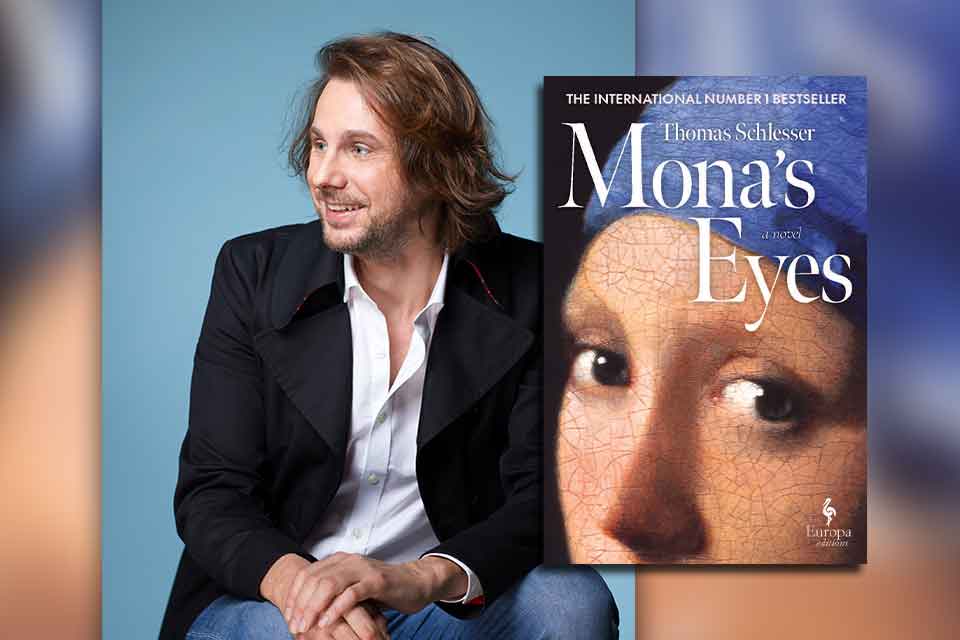

“Look for What Feels Singular”: 5 Questions for Thomas Schlesser

In Mona’s Eyes, after a ten-year-old girl in Paris begins to experience temporary loss of sight, the grandfather she adores begins taking her on weekly outings to museums to visit a single great work of art each week. The novel was an international best-seller and has been translated into thirty-eight languages, including Braille. In its translation by Hildegarde Serle, published by Europa in 2025, French writer Thomas Schlesser makes his English-language debut.

Q

This is the first novel I’ve read that is organized around works of art. We begin in the Louvre, viewing Venus and the Three Graces Presenting Gifts to a Young Woman, by Sandro Botticelli (1475/1500), and end with an abstract piece by Pierre Soulages (2002). In addition to the detailed description of each work of art in the text, the dust jacket folds out and becomes a poster of each piece viewed in the novel. As readers, we’re seeing in more than one way. I used the jacket as a reference while reading, but the detailed descriptions would also work well in audio. Did you have this presentation in mind when you wrote the novel? How did this stunning cover come about?

A

There’s something quite remarkable about the writing process of Mona’s Eyes. When I began it twelve years ago, in 2013, I already knew the story would revolve around the theme of blindness. But I didn’t want blindness to be just a theme—I wanted the book itself to respond to that challenge, to have a performative and inclusive quality. I wanted it to be a novel that, while entirely devoted to the visual arts, could also be addressed to those who cannot see, who are losing their sight, or who experience the world differently. That’s why the book is filled with ekphrases—those detailed, almost tactile descriptions—which, I hoped, might create a kind of hallucinatory effect, even for readers who cannot actually see the works.

Still, my French publisher at Albin Michel, Nicolas de Cointet, had the wonderful idea of adding something completely unexpected: a dust jacket that unfolds into a visual map of Mona’s journey—a kind of imaginary museum tracing her path through art. It’s a beautiful object, and I must admit it adds an extraordinary extra dimension to the reading experience. Yet originally, I would have been perfectly happy for the book to exist without a single image.

Q

You’re an art history professor and have written several nonfiction works about art, artists, and the relationship between art and politics. Whose work are you most excited about at the moment? Are there any contemporary artists whose work you’re particularly drawn to?

A

I’m a passionate and endlessly curious art lover. I take great pleasure in discovering new artists, especially contemporary ones. For instance, I deeply admire Pierre Huyghe, a French artist living in the United States. I’m also a great admirer of Christopher Wool’s work. And in Mona’s Eyes, I tried to express my admiration for contemporary art through the presence of Marina Abramović, whom I consider one of the truly essential artists of the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries. Through performance, she brings the political and social dimensions of art into a direct, physical experience.

In my research—for example, in books I’ve written on art and freedom of expression, or on the relationship between art, dream, and imagination—I’ve sought to explore how art and authority intertwine in complex ways. That’s also the case in Mona’s Eyes. Even though it’s a novel and not an essay, it includes the figure of Jacques-Louis David, the great eighteenth-century painter who, despite his genius, served highly questionable regimes, from the Reign of Terror in France to the rule of Napoleon. I wanted to remind readers that while art can elevate, inspire, and liberate, it can also, at times, lend its strength to domination. We must therefore look at images not only with admiration, but also with awareness.

Q

Going to the Louvre can be a bit overwhelming. In the novel, Mona and her grandfather view only a single piece each week. What suggestions do you have for those who don’t live in Paris when they’re visiting the Louvre? What is the best way to approach it?

A

I don’t really have advice to give about how to visit a museum—there are a thousand possible approaches. What I do know, however, is that the temptation to want to see everything is simply impossible to satisfy. That’s true at the Louvre, of course, but it’s true in any major museum. My suggestion would be not to look only for what seems conventionally beautiful, but for what feels singular—what stands out, even if it isn’t immediately pleasing. Always ask yourself what is most particular, most different.

Above all, I would say: trust your emotions. In Mona’s Eyes, I find something interesting in this respect—Mona sometimes feels bored in front of a work of art. It happens, for instance, when she looks at a painting by Raphael. Raphael is a truly great artist, yet it’s not surprising that he can provoke a sense of boredom today. We live in an era that prizes agitation, movement, and transgression, whereas Raphael embodies harmony and balance. That can seem, to contemporary eyes, a little static or distant.

So, a negative reaction to a work of art can also be revealing—it helps us understand how taste evolves, how the very idea of beauty changes over time. I would say two things, then: first, look for what feels singular, even if it doesn’t fit your idea of beauty; and second, trust your emotions—they will teach you a great deal about the work itself.

Q

What trend in culture has recently captured your attention?

A

That’s a fascinating question. Let me begin with a small caveat: it’s of course impossible to generalize across an entire era or the whole planet. But broadly speaking, in the Western cultural scene from the 1970s to the early 2010s, there was a dominant taste for hedonism, youthfulness, and the celebration of transgression—especially erotic transgression. This was visible across all artistic fields, from Madonna’s songs to Jeff Koons’s sculptures and paintings, and through to literature and film—in the provocative writings of Catherine Millet, for example, or in the raw, unsettling cinema of Larry Clark, both of whom explored sexuality and freedom with striking audacity.

Then, starting in the 2010s, new and often very engaged concerns emerged—sometimes, admittedly, pushed to extremes—with three main axes: gender inequality, racial inequality, and the environment. A whole new generation has, in many ways, stood up against the libertarian exuberance of the one that came before it. As a historian, I find that shift deeply interesting—not to take sides, but to observe how these cycles unfold.

What also fascinates me is how every movement of thought, however revolutionary it may seem at first, eventually becomes its own form of convention. It’s a little sad, perhaps, but also very telling: all forms of nonconformity end up turning into a new conformism. And if I may venture a prediction—a risky one—I wouldn’t be surprised if, in the years to come (though there’s no sign of it yet), we see a return to a kind of formalism, a renewed care for “art for art’s sake,” detached from overt social or political concerns. It’s not that I wish for that, but history often advances through these pendulum swings—one sensibility building itself in reaction to the one that came before. That said, I’m very aware that I’m speaking here in broad generalizations, and they deserve to be taken with nuance.

Q

What is reading life like in France? Are brick-and-mortar bookstores thriving? Are translations popular? Do you have influencers, like we do here in the US, who drive selections with their book club picks?

A

I would say that in France, reading is considered a matter of public interest. It’s supported by many parts of civil society—booksellers, associations—but also by public institutions: schools, the Ministry of Culture, and organizations such as the Centre National du Livre. All these actors agree on the importance of encouraging young people to read, even as reading habits are declining in a rather alarming way.

There’s a clear awareness of the issue, and a shared desire to keep France a nation of readers and writers—a country open to the cultures of the world. And in that regard, we’re very fortunate: France has extraordinary translators and publishing houses that actively bring world literature to French readers. That international openness is, to me, essential and deeply healthy.

That said, it’s impossible to ignore the devastating effect that the more mind-numbing parts of social media can have on our capacity for attention and thought. I’m by no means opposed to progress—the internet holds remarkable resources, including in the visual realm, and offers unprecedented access to knowledge. But one must also acknowledge its dulling power. I often say that reading even a single poem a day—a simple fourteen-line sonnet, for instance—can make you feel that your day has been shaped by something profound, sensitive, and complex. The struggle continues: it’s a struggle for intelligence, and for the emancipation of the mind through reading.

Thomas Schlesser is director of the Hartung-Bergman Foundation in Antibes, France. He teaches art history at the École Polytechnique in Paris and is the author of several works of nonfiction about art, artists, and the relationship between art and politics. He is the grandson of André Schlesser, known as Dadé, a singer and cabaret performer who founded the Cabaret L’Écluse. Schlesser was named 2025’s Author of the Year by Livres Hebdo.