“The Pain That Adjoined Me as a Twin Since Birth”: A Conversation with Kurdish Poet Hussein Habasch

Hussein Habasch is a poet from Afrin, Kurdistan, currently based in Bonn, Germany. Ming Di is a poet from China currently based in California. They met at the International Poetry Festival of Guayaquil in Ecuador in 2017 and the Safi International Poetry Festival in Morocco in 2018. The following conversation, conducted by email, touches upon Habasch’s exile from Kurdistan, those who inspire his poetry, and more.

Ming Di: Hello, Hussein. What was Afrin like when you grew up there? And the Afrin River? Your parents used to live in the city of Aleppo? Such an ancient and historic place.

Hussein Habasch: Afrin was a paradise on earth in every sense of the word, with mountains and amazing nature, with rivers, springs, and dense forests, where millions of olive trees stretch in front of balconies and in its plains that extend as far as the eye can see, where its 365 villages are scattered like olives or pearls on its hills and on the slopes of its mountains, where the beauty is endless. When you enter it, the scent of roses will never leave your nose for the rest of your stay! It is the city of God on the shoulder of my heart, as I once called it in one of my poems.

Although it belonged to Syria and was not under Kurdish sovereignty, it was not subject to war at the time. After the 2018 war, everything changed. The Turks began displacing the Kurds from the city and its villages, and the demographic change took place in a systematic and planned manner as more than three hundred thousand Kurds were displaced. Neither people nor trees nor stones were spared, but I prefer not to talk about it here.

As for the Afrin River, it is like my artery that runs through the body of the city, dividing it into two halves of love and beauty, and irrigating the fertile lands and fields with unparalleled love! It is my river, like the Rhine River, which also divides the city of Bonn, where I live, into two halves! As for my parents, they lived in my hometown of Şiyê and only lived in Aleppo for a few years. I studied and lived in Aleppo for more than twenty years. Yes, it is indeed an ancient city, but unfortunately the war has destroyed it.

Di: Born in the junction of four modern countries—Turkey, Iraq, Iran, and Syria—what does “border” mean to you?

Habasch: “Border” is a dirty and terrifying word. It means barbed wire; it means hatred, fear, and loss of hope. It means bullets and killing if you try to cross it. It means the division and occupation of Kurdistan by Syria, Turkey, Iraq, and Iran. Border means dying of heartbreak as you look at the other side where part of your family and relatives are and you can’t shake their hands, hug them, or talk to them. Ever since humans invented borders between them, they invented conflicts between them and diminished their humanity.

Ever since humans invented borders between them, they invented conflicts between them and diminished their humanity.

Di: Do you write in Kurmanji Kurdish to preserve your native language and cultural identity?

Habasch: I write in Latin letters using words from almost all Kurdish dialects such as Kurmanji, Sorani, Zazaki, Gorani, Luri . . . As is well known, the Kurdish language was and still is banned, suppressed, and unaccepted by the countries that occupy Kurdistan. Because of this ban and denial over the years, the Kurdish language did not develop as desired, and it remained confined within family members and friends. It has not become a recognized language in schools, institutes, universities, or the press (whether written, audio, or visual). So, writing in Kurdish is to challenge the languages of the occupiers.

To me personally, writing in Kurdish is to go out into the open air, the air of freedom, beauty, and creativity. Writing in Kurdish is writing with pure, clean, and healthy mother’s milk. It is nourishing from the origin, the wellspring. It is to introduce to the world the linguistic and cultural identity and creativity of the Kurdish people. It is also to announce that the Kurdish language, despite everything, can produce a sublime literature that should have a place in world literature. I write poetry, and poetry cannot be written in a borrowed language. No literature is as close to the mother tongue as poetry, so I can say that poetry is written in the mother tongue first and foremost. Everything else is of no importance or value.

Di: You received the Hamid Badirkhan Prize for poetry in 2022, awarded by the General Union of Kurdish Writers and Journalists, and you were inspired to write poetry at a young age under the influence of a poem by Hamid Badirkhan (1924–1996), “I Search for Lorca’s Killer.” Can you talk about Hamid Badirkhan and when and where you were reading his poetry? Are there any other Kurdish writers who inspired you to become a poet?

Habasch: I can say that Hamid Badirkhan was my first teacher. When I was a child, I used to see him coming down from his house carved into the side of the mountain to the village square. He was welcomed and respected by all the villagers, including trees and stones. The elders would tell us that he wrote poetry and published books, and that was enough for everyone to respect him without exception. As time passed, and in my teens, I read his poems, especially his poetry book On the Paths of Asia. I liked his famous poem “I’m Looking for Lorca’s Killer.” The poem inspired me, and I wrote a poem along the same lines. Then I tore it up and threw it away, and my cousin didn’t believe that I had written it.

After that, our paths diverged, and he no longer had any significant influence on my poetry. He belonged to what is called socialist realism in literature, so he wrote direct poems through which he wanted to liberate workers and peasants and free peoples from the yoke of capitalism and imperialism and bring the socialist system to nations and peoples without paying much attention to the aesthetics. As for me, after I passed the stage of childhood and adolescence, I found my way somewhere else, and I saw that the first goal was to write good poetry and preserve its artistry and aesthetic values above all, whatever topics it addressed or touched on. For me, poetry is working on the gift of beauty, elevating it, transforming the ordinary to the miraculous and extracting its jewels. It is also taking paths that no one has taken before. Of course, I try. I may succeed or fail, which is not important; the most important thing is the effort of trying.

Other Kurdish writers who inspired me to become a poet? Yes, there is the great poet and philosopher Ahmad Khani, the author of the immortal epic Mem û Zîn, as well as the great poet and Sufi (mystic) Malaye Jaziri, the author of the great collection named after him, Malay Jaziri’s Diwan. Also the great modernist poet Sherko Bekas, the author of a wonderful book of poetry, Butterfly Valley (WLT, July 2018, 44).

Di: Since very little has been written about the Kurdish literary tradition, or I am not familiar with it except “Mem û Zîn,” can you talk about Kurdish references in your poems?

Habasch: My poems have benefited and continue to benefit from Kurdish tales, stories, fables, legends, and epics, from the Kurdish oral heritage, from ancient Kurdish folklore and singing, from Kurdish dictionaries that I do not dispense with, from history books, from the picturesque nature of Kurdistan, from Kurdish dialects rich in vocabulary, from early great poets like Ahmad Khani, Malaye Jaziri, and Faqi Tiran, from the Yazidi and Zoroastrian heritage. However, I must mention here that all these have multiplied with age, and they do not stop at the Kurdish but, rather, extend to international references. My poems benefit from all the world’s poetic heritages, both ancient and modern. But I believe that the imprint of my poems is similar to the imprint of my heart, soul, and imagination, whatever the references.

My poems benefit from all the world’s poetic heritages, both ancient and modern.

Di: How is your life in Germany? What year did you move to Bonn? Do you live in a Kurdish community? Is there literary support for diaspora writers or writers in exile such as publishing opportunities or reading events there?

Habasch: My life in Germany is a routine, from home to work and from work to home. I don’t have friends in the Nietzschean sense of friendship, like the air we breathe. My real friends are the Rhine River, Beethoven, August Macke, the birds flying in the sky, and my boundless imagination. I have been in Germany since late 1996 and in Bonn since 1999. I am not a social being, and as I said, I live in almost complete isolation. I live in double exile: the exile of distance from my homeland and the exile of isolation. The exile of isolation is by choice, of course. But from time to time, I participate in some of the demonstrations that Kurds organize to make our voices heard. Of course, every year on March 21, I participate in the celebrations of Newroz, which is celebrated by Kurds in Kurdistan and all over the world. Newroz is the national holiday of the Kurdish people.

There isn’t any literary support for diaspora or writers in exile. There are no publishing opportunities except very rarely. There are no real reading events. Some evenings and events are held here and there for publicity or to fulfill some duty, but their ultimate goal is not poetry or listening to it and enjoying the real word or feeling the beauty, except rarely.

Di: You have traveled around the world for poetry festivals. Has traveling affected your poetry writing?

Habasch: Of course. Traveling always saves me from exhaustion, constant fatigue, and the routine that envelops life and poisons it with dullness and lack of desires. It is an effective remedy against psychological, intellectual, mental, physical, and spiritual crises. Traveling provides me with energy and rejuvenation, helps me to regain vitality and focus, and gives me wide spaces to relax, meditate, and move my imagination toward creativity and writing. By traveling, I am in direct contact with different and diverse languages, customs, beliefs, and cultures from which I learn a lot.

The benefit is double if traveling for poetry and participating in poetry festivals because I meet fellow poets from different countries and continents, listen to them recite their poems, converse with them about poetry and literature, ask them about their countries, and learn their news and conditions. These are all important triggers and materials for writing. So, in traveling, I change, renew, discover, learn, evolve, develop, enrich, venture, get to know myself better by getting to know others, gain knowledge and wisdom, and experience fun and madness. In ordinary life, I walk; in traveling, I fly. All this has influenced my poetry writing in one way or another.

In ordinary life, I walk; in traveling, I fly.

Look, my friend, at what the great German poet Rainer Maria Rilke says about travel and its importance for writing and creativity: “Poems are experiences. For the sake of a single poem, you must see many cities, many people and things, you must understand animals, must feel how birds fly. . . . You must be able to think back to streets in unknown neighborhoods, to unexpected encounters, and to partings you had long seen coming . . . to nights of travel that rushed along high overhead and went flying with all the stars.” Rilke was right, of course.

Di: At Sarajevo’s International Poetry Days Festival, you received the international “Bosnian Stećak” award, one of the most important Balkan prizes for literature. The prize was previously awarded to the Polish poet Tadeusz Różewicz, the Palestinian poet Mahmoud Darwish, the American poet Charles Simic, the Swedish poet Lars Gustafsson, the German poet Michael Krüger, the Swiss poet and writer Ilma Rakusa, and others. How do you feel about being among so many great poets and writers?

Habasch: There is no doubt that receiving this prestigious award—which was received before me by all these great poets and writers, and seeing my name among them—was a source of great happiness and honor for me. This award embodies great value and special significance to me because it came from a country that had been ravaged by war for a long time and miraculously survived. In other words, its fate during the war was similar to that of my country, Kurdistan. But it survived the war while Kurdistan, unfortunately, has not yet. Therefore the citation of the award states that Hussein Habasch is a special poet. In a way, he writes poetry that resembles and is close to us, because he writes about the destruction of the Kurdish homeland and the terrorism practiced against the Kurdish people. It also states that “The Sarajevo Poetry Days Council has awarded you the award, which represents high appreciation of your distinguished poetic work and your contribution to literature that glorifies freedom and human values.” My thanks to them for appreciating my poetry and writings.

Di: From your poem “I Am Sorry, Mother!” I learned about your siblings living in several countries and some living in refugee camps. What is “home” to you?

Habasch: Yes, in that poem I apologized to my mother on behalf of my brothers and sisters scattered in camps and exiles around the world against their will. I apologized to our great mother whom we caused great pain by our long absence from her sight; we caused her great pain and sorrow, which unfortunately continues to this moment. We, her daughters and sons, have been unable to visit her and embrace her because of the wars, forced exile, and occupation of our home. Our sadness is great and our pain is deep, we Kurds, my friend, and almost no one in the world feels us.

As for what home is for me: Home is freedom. Homeland is equality, justice, and living with dignity. Homeland is that geographical area that gives you life, air, sunshine, white and dark clouds. Homeland is to live unshackled by the shackles of others, to be your own master and to be ruled by no one else. Homeland is Kurdistan that yearns for freedom and sacrifices tens of thousands of victims to achieve its independence. Homeland is Kurdistan from the beginning and the end, and my dream is to see it liberated and independent before I die.

Di: I was struck by this line in one of your poems: “the pain that adjoined me as a twin since birth.” You write more about love and resistance through love. Your poems are sad but not gloomy, mournful but not melancholy, painful but not sentimental. I would like to conclude this interview by reciting the end of your poem “A Dialogue”:

What is the future, father?

It’s a sun that only shines on the lucky ones, son!

What are tears, father?

It’s rain that missed its way, son!

What is bravery, father?

It’s a ball of fire that rotates inside the heart, son!

What is pain, father?

It’s a shirt we wear from our birth to our death, son!

Habasch: Thank you, my friend. Thank you for your beautiful and deep questions. And I will conclude with you here and say love, only love, will save us. Our salvation as human beings hangs on love.

May 2025

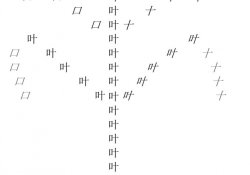

Tomorrow, You Will Be an Old Man

by Hussein Habasch

translated by Hussein Habasch

(For me, in a quarter of a century, more or less)

Tomorrow, you will be an old man

The cane, always with you

You will walk alone

You will mutter to yourself like all old geezers do

You will become obstinate, hard of hearing, and slow

You will ask for help when you need it

But no one will respond

You will dream of the past

And the good old days

While your grandson will think of the future

And days to come

You will curse this vapid generation

Repeating itself like a broken record

How wonderful our generation was!

You will be the butt of jokes in the family

They will laugh at you and your positions

Which you think are right on

Your lips will let out a sarcastic smile

Whenever they mention words like “stubbornness,”

“Vigor,” and “faith in the future”

You might even laugh

Your bones will soften

Illnesses will roam freely in your body

Without permission

All your desires will be extinguished,

Except the desire to die

There will be no friend or a companion

Loneliness will be your support and comrade

You will always be ready to depart

The threshold of the grave will entice you

And keep you company

All the angels will betray you and leave

Only Azrael will approach you as a last friend

Perhaps you will say just as you are about to go:

If I die bury me here in the strangers’ cemetery

Perhaps these words

Will be your final wish.

Translation from the Kurdish

Hussein Habasch (b. 1970) is a poet from Afrin, Kurdistan. He currently lives in Bonn, Germany. He is the author of many books, and his poetry has been published in more than 150 international poetry anthologies and translated into many languages. He has participated in many international poetry festivals and has won several awards, including the Great Kurdish Poet Hamid Badirkhan Award and the International “Bosnian Stećak” award for poetry.

Hussein Habasch (b. 1970) is a poet from Afrin, Kurdistan. He currently lives in Bonn, Germany. He is the author of many books, and his poetry has been published in more than 150 international poetry anthologies and translated into many languages. He has participated in many international poetry festivals and has won several awards, including the Great Kurdish Poet Hamid Badirkhan Award and the International “Bosnian Stećak” award for poetry.