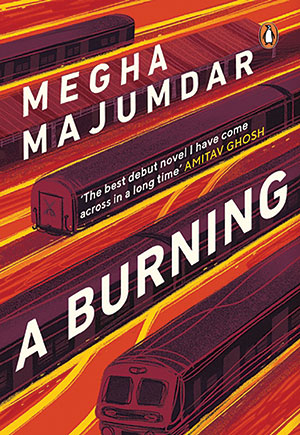

A Burning by Megha Majumdar

New York. Alfred A. Knopf. 2020. 293 pages.

New York. Alfred A. Knopf. 2020. 293 pages.

MEGHA MAJUMDAR’S debut novel, A Burning, narrates the ramifications of a terrorist attack—as indicated by the title, the burning of a local train in the vicinity of a Kolkata slum—through an incisive examination of the lives of three characters: a young Muslim salesperson, Jivan; a trans person with ambitions of becoming a professional actor, Lovely; and a disenchanted physical education teacher, plainly called PT Sir. The novel is comprised of their interspersed narratives, affording each character voice and interiority while allowing Majumdar to shift among their differing trajectories in the aftermath of the attack. Although tightly knit and fast-paced, very much in the style of a crime novel, this text is less invested in illuminating the cause of the titular event and more oriented toward using the event to interrogate several pressing issues of our times: the role of dissent in a democracy, media trials, the appeal of populist politics, mob lynching, and the limits of civil liberties, among others.

While the novel’s immediacy derives from its allusions to contemporary events in the subcontinent, particularly the rise of right-wing populism accompanied by the hounding of religious minorities, it portrays, in granular detail, the anxieties and aspirations of three Indians who seek a life of meaning, freedom, and recognition. For Jivan, freedom comes in the form of a social media post questioning the state’s apathy toward victims of the terrorist attack, while Lovely feels truly unencumbered when performing the role of a mother in an acting class. Interestingly, both of their sections are given to us in the first person, once again adding to the immediacy of the novel. PT Sir’s quest for a life where he does “something patriotic, meaningful, bigger than the disciplining of cavalier schoolgirls” is fulfilled when he at first hesitatingly participates in a political rally, then steadily rises in its ranks, becoming a bureaucrat when the party is voted into power.

However, Majumdar also explores the limits of the quest for freedom primarily through the character of Jivan, who is imprisoned promptly after her criticism of the government, which is seen as overwhelming proof of disloyalty toward the state and affiliation with the terrorists. Much of the novel chronicles her desperate attempts to enlist the help of those who knew her, including Lovely, to clear her name. Meanwhile, Lovely gets a meaty acting part after one of her performances becomes wildly popular online, on the condition that she disentangle herself from Jivan’s case. That visibility and recognition do not guarantee freedom seems to be Majumdar’s rueful point.

The novel is also held together by brief interludes into the quotidian and violent episodes that round out the lives of ancillary characters. One such episode chronicles, in chilling detail, the murder of a Muslim family at the hands of self-styled cow protectors, on the suspicion of them having consumed beef. PT Sir’s apathy and abdication of responsibility in reporting the event—a compromise much needed in furthering a political career—perhaps exemplifies the devastating impact of the cultivated indifference of socially privileged classes in India.

Greeshma Mohan

Jawaharlal Nehru University