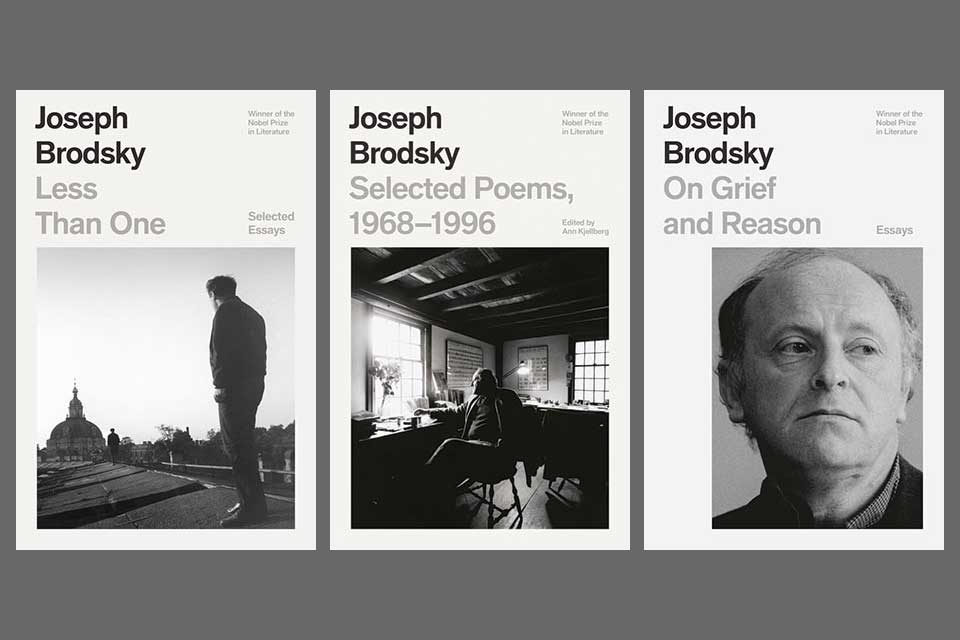

Selected Poems, 1968–1996, Less Than One, & On Grief and Reason by Joseph Brodsky

Selected Poems, 1968–1996

New York. Farrar, Straus and Giroux. 2020. 174 pages.

Less Than One

New York. Farrar, Straus and Giroux. 2020 (©1986). 501 pages.

On Grief and Reason

New York. Farrar, Straus and Giroux. 2020 (©1995). 484 pages.

THE REISSUE THIS YEAR of a number of Joseph Brodsky’s works, to coincide with what would have been his eightieth birthday, could not have come at a more critical time. Before Brodsky’s arrival in the United States in 1972, the poet had passed through many of the shadowy depths that the twentieth century had to offer: wartime evacuation from Leningrad under the siege; arrests and forced “treatments” in Russian psychiatric wards; surveillance and harassment by the KGB; and transport in a prison train (the infamous Stolypin boxcar) on his way to internal exile after a trial based on trumped-up charges for “parasitism.” Due to the courageous efforts of friends, such as the journalist Frida Vigdorova, who compiled a transcript of his trial proceedings that was circulated abroad, his case became known in the West, which facilitated his release from internal exile and, six years later, his eventual expulsion from the USSR.

Despite these experiences, Brodsky (1940–1996) did not consider himself a political poet, rejecting early on the binary choice between “Soviet poet” and “anti-Soviet poet.” Instead, he elected to be an “a-Soviet poet”—which is to say he attempted to write solely out of his own authenticity and inspiration (something with which he was immensely gifted)—and, if possible, to transcend the imposed limitations of his era. This fact, which did not escape the authorities, was observed by those who personally attended his 1964 preliminary hearing and trial, during which he comported himself with dignity and even an air of “peaceful detachment.” His frequently quoted response to the presiding Judge Savelyeva’s question of “Who assigned you the rank [of poet]?” (Brodsky: “Well, I think it was . . . God”) was, in fact, only the tip of the iceberg. Allergic to the idea of victimhood—and having witnessed the great dignity displayed by his mentor Anna Akhmatova in the face of hardship—Brodsky’s goal as an artist was to be, in the face of history’s brutality, a free human being.

Following his trial and release, Brodsky’s arrival in the West was celebrated. As the 1980s progressed, however—and despite, for a time, ongoing sympathy from certain quarters for exiled Russian and Eastern European writers such as Brodsky, Miłosz, Venclova, and Zagajewski—many nevertheless believed that the totalitarian regimes from which these writers had escaped had little in common with our own affairs. Once the Berlin Wall fell in 1989—and after the dissolution of the Soviet empire in 1991—it was thought that the story of the Russian “dissidents” had come to an end. Some even held (though a misinterpretation of Fukuyama’s thesis) that we had arrived at the end of History itself.

In the past decade, however, we have seen that History was at best drowsing and has now returned with a vengeance—this time permeating to greater or lesser extents the whole of what was called, in Brodsky’s time, the West. And as Paul Valéry once wrote, “We see now that the abyss of history is deep enough to hold us all.” For this reason, it is urgent that we return to Brodsky’s works and pay careful attention to his reflections. We read him now as a guide as our universe progressively takes on a hypocrisy, doublespeak, and absurdity that would have been all too familiar to him. Returning to his Nobel lecture included in On Grief and Reason, we understand how Brodsky and his generation felt they were facing a political, cultural, and ethical abyss: “We were beginning in an empty—indeed, a terrifyingly wasted—place, and . . . we aspired precisely to the recreation of . . . culture’s continuity.” For Brodsky, culture was associated above all with dignity and ethics, and its endurance was a necessary component for securing the longevity of truth and civic decency and, as lofty as it might sound, our very survival as human beings.

If this sounded abstract for many in the West thirty years ago, it certainly no longer seems so now. The mixture of ethics and intellectual freedom that permeates Brodsky’s work, particularly in the essays, makes it extremely salutary reading today. And then there is the sheer mastery of Brodsky’s prose. Above and beyond politics, for those who might not have read it, Brodsky’s first volume of essays, Less Than One, is quite simply one of the most brilliant books of literary criticism written in the second half of the twentieth century. That’s a bold claim, but it happens to be true. Written at the height of deconstructionism in Europe, it placed literature at the center of human experience. The essays in On Grief and Reason, including the aforementioned Nobel address, also make for wonderful reading, but Less Than One’s achievement was a difficult act to follow, even for its author.

We have much to thank Brodsky’s literary executor Ann Kjellberg for, with her tireless efforts to edit and watch over Brodsky’s oeuvre. To choose from among the many poems Brodsky produced in two languages for inclusion in the new Selected Poems, 1968–1996 (and keeping in mind that Brodsky’s Collected Poems, published in 2000, ran to 560 pages), Kjellberg had her work cut out for her. This task is also particularly daunting due to the complexity of the corpus: Brodsky’s poetic oeuvre might be best described not as a compendium of poems but as an archaeological site under excavation. To explore it is to be immediately faced with multiple time periods, each layered with key cities and languages. Russian speakers, standing by the canals where Brodsky walked as a young adult, and who can fully appreciate the dexterity and quality of Brodsky’s metrical brilliance, know a very different artist than his English-language readers. Individual translations of poems, such as Richard Wilbur’s masterful rendering of “Six Years Later,” which leads off the new selection, afford only a glimpse into the real meaning of the poems’ formal achievement. English readers are also only acquainted with a small selection of Brodsky’s early poems. Bibliophiles can still sometimes lay their hands on copies of his two very early volumes (albeit flawed, and in the case of the first, disowned by their author) published in the West. Thus it may well be, when all archives are open, and questions of translations put to rest, that future generations will have an even better sense of the poet’s scope than we do.

These are but a few of the things to consider as one approaches the work of this major poet. This year, however, it is perhaps above all critical to take under advisement his warnings regarding personal, artistic, and political freedom, which a rereading of this generous reissue of his works precisely makes possible. For in our ever-more chaotic and illegal century, it is clear that we are progressively facing manifestly dark times ourselves.

Ellen Hinsey

University of Göttingen