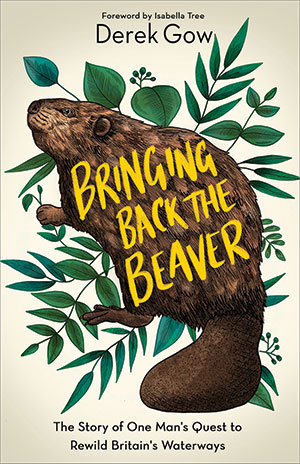

Bringing Back the Beaver: The Story of One Man’s Quest to Rewild Britain’s Waterways by Derek Gow

London. Chelsea Green. 2020. 208 pages.

London. Chelsea Green. 2020. 208 pages.

READERS OF NATURALIST nonfiction will feel at home in Derek Gow’s Bringing Back the Beaver. They will find familiar elements: narrative, passion, research, urgency, ecological significance—right down to the pen-and-ink illustrations for each chapter. Engrossing discoveries lie within, but what may delight readers most is just how often Gow is laugh-out-loud funny.

Bringing Back the Beaver is about restoring this enormous, endearing, eponymous rodent to the United Kingdom. Gow’s book is full of fascinating facts about beavers from antiquity up to the recent past; beginning with the tale of St. Felix of Burgundy, who was shipwrecked on the River Babingley. Felix was purportedly saved from drowning by a colony of beavers out of Norfolk and, in thanks, made the leader of the beavers a bishop. Most of the time, humans have been far more thankless. Gow notes that beaver-bishops aside, they have no patron saint.

To a North American reader, it seems incredible that beavers could have been so utterly destroyed in the first place, until one remembers how intense the trade in pelts was here. So perhaps the first surprise for the beaver novice is how old the trade in beaver is, and that the most valuable part of the creature wasn’t always the pelt but rather the scent glands. These glands could contain a high amount of salicylic acid, depending on the creature’s provender, and thus were highly desired as medicine. In addition, beavers were also used as a Lent-approved foodstuff.

Few people familiar with the landscapes that beavers create can imagine the vitriol Gow has experienced in response to his and others’ reintroduction attempts. Much of this is due to misunderstanding and resistance from gamekeepers, anglers, and estate-holders who fear that the beavers will block the passage of migratory fish (they won’t) or eat game (they’re vegetarian). Gow exposes many old misconceptions such as the belief that beavers were fish (they’re not), had four testicles (they don’t), and could self-amputate their castoreum-bearing cods in order to escape pursuit (just, no). He also describes more recent discoveries such as the Eurasian and “Canadian” beavers cannot interbreed due to a different number of chromosomes.

Gow has looked for the beavers’ traces in histories, stories, and place-names across Britain and seen the fading, obscure signs of their engineering upon the environment. He has searched for their living kin in Poland and Bavaria. Without resorting much to ecological terms such as keystone species or trophic cascade, Gow makes a strong case for how much the beaver’s influence is needed. It is his contention that the best lands ancient humans settled were first prepared and enriched by the beaver. Ignorance about this important species has robbed many places of their extremely important work of flood control and habitat creation.

Gow is funny, irreverent, and as hostile to bureaucracy as Edward Abbey. No human being nor organization is spared, though he holds a special place of ridicule for DEFRA, the UK’s Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs, an agency that seems eager to play the fool. Neither are his dear colleagues and fellow beaver-believers exempt from his ribbing. One aging arborist is described as “now as old and gnarled as an Ent with a complex system of underpants containing so many forms of ancient fungi that the government’s nature authorities are preparing to declare them Sites of Special Scientific Interest (SSSI).” There are passages so hilarious that readers must read them aloud to all nearby, such as a demonstration of beaver sexing gone comically awry, Russians attempting to create beaver-based circus acts, or an account of British farmers engaging in nigh unprintable drinking games on field trips to the continent.

While human beings are frequently the butt of his jokes, Gow is deeply empathetic with beavers themselves, and some of the most arresting places in the book imagine beaver-hunting from their perspective. While jarring in relation to the humorous passages, Gow’s descriptions are too factual to be lugubrious. One leaves the book feeling that beavers are people, too. And probably the better persons.

Bringing Back the Beaver is thoroughly entertaining, which in these times is an achievement for environmental nonfiction. Part of this is the author’s genuine affection for these busy creatures. The fact that this book is a comedy in the best sense helps—there is a hopeful ending here. After much bureaucratic inertia and misinformation, the repatriation of the beaver to Britain is well underway. Gow’s epilogue describes settings that will become more and more common as the beaver once again replenishes wetlands, creates systems of lakes and ponds, and establishes diverse habitats that, until recently, were lost.

Greg Brown

Mercyhurst University