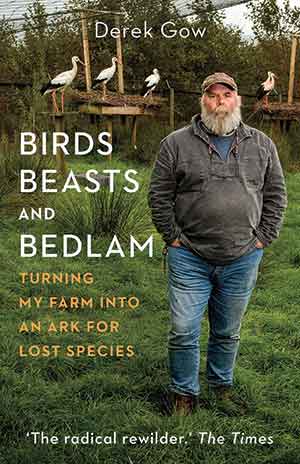

Birds, Beast, and Bedlam: Turning My Farm into an Ark for Lost Species by Derek Gow

White River Junction, Vermont. Chelsea Green. 2022. 208 pages.

White River Junction, Vermont. Chelsea Green. 2022. 208 pages.

THE MUSKY BREATH of the Polish bison bulls, cloudy in the cool green thicket of the deciduous understory, is a difficult thing to make out amidst the busy and verdant bush and vine, but once you notice the bulls, their bovine haunches, blustering and magnificent, you’ll understand. Such a scene animates Derek Gow’s introduction to his second book, Birds, Beasts, and Bedlam, a detailed and cartwheeling accounting of the years of his life spent torpedoing, more or less, to a goal equal in glory to the hallowed sight of Polish bison bulls in a British forest. Like the biodiverse brush singing and squawking with life of all sizes, his story is both riotous and rich, housing an indiscriminate crowd of yarns and characters, who, like the buzzing of insect life within the holly and honeysuckle, catch the attention of and confuse the eye of the reader in their tumult. Gow writes with abandon, tattling off tales with the loquacity of a folklorist, or any salty farmer worth their salt. Luckily for us, the splendor of his life’s work, and its ecologic importance, emerges as conspicuously as a bison in a raspberry bush, shaking and stomping.

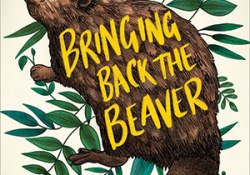

Gow is about as far from the image of a buttoned-up conservationist as it gets, and part of that is due to the freshness of his philosophy. As one of Britain’s loudest proponents of rewilding, Gow has come into disagreement with an array of other nature-minded folks, or at least their ideologies: farmers worshipping the “great false idol of the industrial machine,” the margins-oriented folk at larger conservation organizations failing to notice the importance of breeding unflashy or challenging species, more traditional conservationists without the imagination to surmount bureaucratic obstacles or envision the return of long-lost species. Gow has no such dearth of imagination, nor of tenacity. His success in facilitating the return of once-common creatures like beavers, water voles, storks, and wildcats, like his successes as a writer, can be attributed in part to his ability to envision and create a new, bucolic reality without much concern for the status quo; he has no interest in fitting in, or doing what everyone else is doing.

To be clear, Gow is more outlier than outlaw. It takes a perceptive sort of person to first see, clear-eyed, that the monocropped sort of fields paired with landscapes dotted with only one sort of efficiently fattening livestock is a problem, and to understand how policy, economics, and agricultural trends shaped Britain’s meadows and forests into lifeless rectangles. But that astute person must also have a single-minded fearlessness, along with plenty of guts, to actually devote their life to housing and breeding Britain’s wildlife back from extinction, especially when that wildlife can bite—or break a grown man’s neck.

Gow’s passion for his creatures, and their ecological importance, brighten the pages of Bedlam, which otherwise sometimes run wild with descriptive delirium, but his illustrations are the highlight of the book. While, as a writer, Gow sometimes finds himself lost in the weeds, as an artist he transcends. Pen-and-ink visions of soft-feathered baby chicks, roosting under their mother’s wing in a bed of roses and thistle, or of voles huddled close in a grassy nest, convey his central goal of returning wildlife to their ecological niches, where they can build dams and nests, stomp and smash trees, life begetting more life, noisy and lush. While a reader like myself may find the cadence of his written work difficult to embrace, with his galloping sentences leaving not much space for the reader to breathe, those electrical illustrations with their vibrating linework and pulsing life come alive on the page to speak: make Britain wild again.

Lucie Nolden

Bowdoin College

When you buy a book using our Bookshop Affiliate links on this page, WLT receives a commission. Thank you for your support!