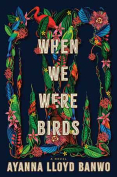

When We Were Birds by Ayanna Lloyd Banwo

New York. Doubleday. 2022. 288 pages.

New York. Doubleday. 2022. 288 pages.

ONE WOULD HARDLY expect a book that is wholly preoccupied with death to be full of energy and vibrant imagery, but that is just one way that Ayanna Lloyd Banwo’s debut novel delights and surprises. A magical-realist love story set in the author’s native Trinidad, When We Were Birds is a painstakingly wrought exploration of the relationship between living and dead. Just as importantly, though, it is a novel about connection—to one another, to the places that form us, to our ancestors and their legacies, and to local and global histories.

Darwin and Yejide are complex characters with distinctive points of view, and as the narrative perspective switches back and forth between them, we can anticipate the ways they will come to fill in the other’s story. Darwin is a Rastafarian struggling to reconcile his new job as a gravedigger with his religious beliefs, which prohibit contact with the dead. He has recently become estranged from his mother, with whom he previously had a close and loving relationship, because she cannot abide his choice of work. Yejide, on the other hand, has never felt close to her mother, whom she describes as “a womb and a grave; a cage and a pair of wings; a feeding tube and a noose.” This ambivalence extends to her feelings of taking on her mother’s role of matriarch for the dead, which she seemingly has no choice but to assume when her mother dies. By the time Darwin and Yejide finally meet, halfway through the novel, each is in the throes of a painful negotiation of fate, self-determination, and maternal loss.

Banwo’s commitment to voice and place remains consistent throughout the novel. It is brought to life through her use of Trinidadian Creole and in her attentive detail to the sights and sounds of the fictitious Port Angeles and the surrounding countryside, which ground us in the physical so completely that even the supernatural becomes an extension of the protagonists’ reality. Most of the novel’s action takes place in two locations: the lush and decaying cemetery Fidelis and the house at Morne Marie, a former cacao plantation turned supernatural safe haven for generations of Black women who help the dead transition into a peaceful afterlife. In both places, it seems, Darwin and Yejide grapple with their sense of obligation to those who have passed on: “Is not a good thing to disappoint dead people. They does take it hard.” And as it turns out, both Darwin and Yejide find themselves implicated in preserving the integrity of the dead in their care, each in their own way, as they fall in love.

The novel’s engagement with this region’s violent historical past is implicit until near the end, when Yejide considers that it “is not only headstones that make a place a burial ground. . . . It don’t have a single place on this whole island that don’t house the dead.” Her comment speaks directly to the violence that established her maternal lineage at Morne Marie, yet it also serves to remind us of the kind of violence done to enslaved Africans, Indigenous peoples, and indentured workers across the Americas. The imperative to do right by one’s ancestors is thus suffused with additional urgency, a commitment to justice that further binds the living and the dead.

It makes sense, then, that the novel begins and ends with the recognition that storytelling is one of humanity’s most crucial tools for harnessing the power of memory. Stories that “echo like old truths” are elemental, a kind of existential interdependence binding generations to one another. Without ancestors, how would we know who we are? And without us to remember them, what would happen to the ancestors?

Ann Marie Short

Saint Mary’s College

When you buy a book using our Bookshop Affiliate links on this page, WLT receives a commission. Thank you for your support!