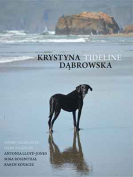

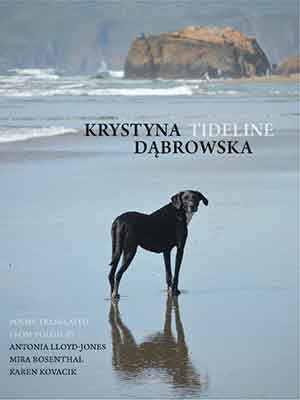

Tideline by Krystyna Dąbrowska

Brookline, Massachusetts. Zephyr Press. 2022. 162 pages.

Brookline, Massachusetts. Zephyr Press. 2022. 162 pages.

KRYSTUNA DĄBROWSKA (b. 1979) has published five volumes of poetry and won prestigious prizes, including the Kościelski Prize, the first Szymborska Award in 2013, and the Literary Award of the Capital City of Warsaw in 2019. A photographer and a graduate of Warsaw’s Academy of Fine Arts, she recently brought Louise Glück and Nuala Ní Dhomhnaill into Polish. Since her poetic debut in 2006, she has been translated in twenty languages. Her first full volume in English, Tideline includes translations from her first four poetry collections: Biuro podróży (Travel agency); Białe krzesła (White chairs); Czas i przesłona (Time and aperture); and Ścieżki dźwiękowe (Soundtracks). Many of these poems have seen prior publication: in Harper’s, Harvard Review, Brooklyn Rail, Southern Review, and Los Angeles Review, as well as in Scattering the Dark, an anthology of Polish women poets edited by Karen Kovacik. Kovacik is currently translating Dąbrowska’s fifth book, Miasto z indu (City of indium).

Offering glimpses into the proverbial “it takes a village,” Tideline begs the question of how to best present an author’s work in translation. One solution retains the translators’ individual styles and allows the reader a rare opportunity to experience a simultaneous multivoiced approach to the poems. Another solution eliminates all but one filter between the original and the translation and unifies the translators’ polyphonic voices, including the differences between British English and American English. Encouraged by Zephyr’s editor, Christopher Mattison, who tightened the translations and smoothed out differences of diction and style, Tideline shows a high level of stylistic integration while retaining the essential personality of each translator—a model of collaboration.

Tideline is a translation “by eight hands,” if one counts the poet’s participation. The book cover was chosen from one of Dąbrowska’s photographs that reflects both the volume’s title and the poem “Yesterday I Saw a Dog at the Tideline” in Rosenthal’s translation. Kovacik shaped Tideline’s structure, defining a loose thematic structure in four numbered but untitled sections for which she selected three dozen poems, ensuring a balance among the translators’ contributions across each section. Adding a subtle reference to the order of publication of Dąbrowska’s volumes of poetry, the eponymous title poems of her first, second, and fourth books, “Travel Agency,” “White Chairs,” and “Soundtracks,” are placed in sections 1, 2, and 4, respectively. The eponymous poem of Dąbrowska’s third volume of poetry, Time and Aperture, is echoed in the theme of the third section. Section 1 focuses on travel and water, Section 2 contains speculations about self and other, section 3 includes personal and family memories and survival, and section 4 focuses on artmaking.

None of these editorial and methodical choices are explained in the volume, however, forcing the reader into active reading—frustratingly unsettling for some, fun guessing for others. How best to read? To count or feel? To deconstruct or to dive into the poems? This reviewer, for example, only noticed the translators’ initials at the bottom of each poem upon a second reading. Regardless, the poems take one straight to language, rhythm, and style. The images and alliterations, so important for a visual poet such as Dąbrowska, are felicitously translated. The translation has an unhurried, conversational feeling that smooths the terseness of some of the Polish phrasing, especially when the sentences and verses’ caesura deviate from the original. But it is the organization of the volume, and in particular the fluid, overlapping themes of the four sections, that convincingly lead the reader into Dąbrowska’s world. This organization mirrors her true poetic personality, namely her journey to the apparent simplicity that characterizes the most difficult works of art. This is indeed quite a tour de force.

What emerges is a poetry suffused with the ability to notice the imperceptible, subtle, intimate origin of change and to anchor it in visual cues—a refreshing, quietly revolutionary approach. The poet describes the modes by which people relate to each other as if tied by an invisible umbilical cord—like an unleashed dog always returning to the shoreline. This journey from one solitude to another also leads us to choose between the heat of the day and the cold of night, just as the moon is pulled between the earth and the sun “unless a sudden ray connects the trio of planets. / . . . the two rivals combine their forces of attraction – / then breath is at its deepest, the highest wave rises.” As Rosenthal points out in her afterword, Dąbrowska’s discreet way of bridging the mundane and the spiritual transcends mere description. By slightly altering our angle of consciousness, the poet opens up space for transforming our relationship to reality. Neither hermetic nor “in the moment,” her multilayered poems weave everyday images of the internet, metro, tourism, and consumerism, with deeper memories and cultural references. Her images are often set as film scenes in a language that is both precise and modern, such as in the poem “Names.” Her poems are born from a strong feeling—an illuminating image that only later imposes itself as an unpredictable poem.

Fittingly for a poet who won the first Wisława Szymborska award, Dąbrowska often turns reality upside down, as in section 1 of Tideline. In “Travel Agency,” the speaker facilitates the travel of the deceased to the dreams of their loved ones. The poem “Oceanarium” could be read as an inversion of Elizabeth Barrett Browning’s “How Do I Love Thee.” The next poems mock the proliferation of so-called “security questions” imposed by the internet world or by the poet seeing the skyline and streets of Cairo through the presence of its many urban goats. This ability to see differently gives Dąbrowska some of her most beautiful lines, such as in the poem “White Chairs,” which opens: “Let dailiness in poetry be like the white / plastic chairs by the Wailing Wall” and closes with “Let dailiness in poetry be like these chairs, / which vanish to make room / for a circle dance on the Sabbath.”

Alice-Catherine Carls

University of Tennessee at Martin

When you buy a book using our Bookshop Affiliate links on this page, WLT receives a commission. Thank you for your support!