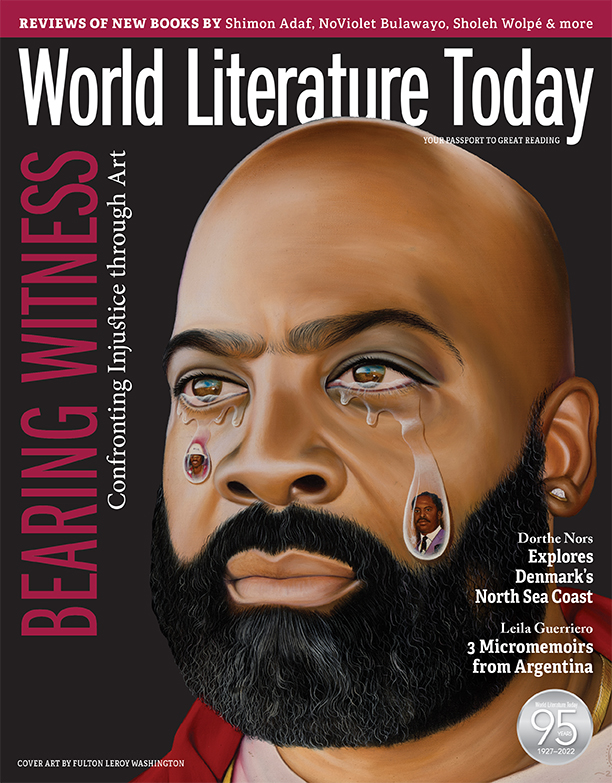

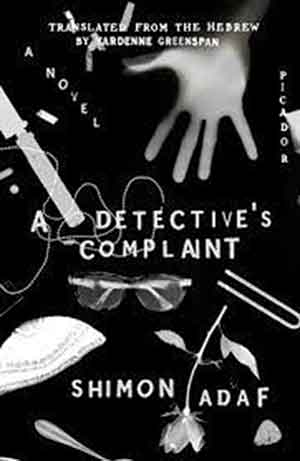

One Mile and Two Days Before Sunset, A Detective’s Complaint, & Take Up and Read by Shimon Adaf

London. Picador. 2022. 336, 384, and 688 pages.

London. Picador. 2022. 336, 384, and 688 pages.

SHIMON ADAF’S Lost Detective Trilogy embodies many worlds, attitudes, genres, and voices. Like Walt Whitman and Bob Dylan, it contains multitudes. Philosophy, literary theory, immunology, temporal rifts, and religious texts mingle together in this trilogy to produce a work that attempts to mimic what Adaf believes is a deep truth: that people are not closed systems but nodes in a network of relationships. People are constantly exchanging bacteria and viruses with one another, their perceptions of time and space don’t line up, and one person’s individual trauma as a guinea pig in a concentration camp can be the portal to a major discovery about the nature of human consciousness.

Like Adaf’s previous novel in English, Sunburnt Faces, the Lost Detective Trilogy never loses sight of itself as a literary work. This might make the books sound pretentious, but they are actually the opposite: they are attempts to lodge a creative object, born of a human mind, squarely in the space between the intangible and tangible aspects of our lives. A book has weight and takes up space, but the weightless words within it are woven together by a mind that exists as part of a brain, which is attached to a brain stem, which receives blood and oxygen and impulses from the rest of the body. As one major character declares in the third book, Take Up and Read, “the true key” to understanding what a human is is the immune system, that “its entire function was to recognize what belonged in the body and what was foreign to it. It learned and it had a memory, and it was founded on the fact that the body is a microbiome.” Adaf has written a story that incorporates the latest scientific ideas about the importance of the immune system and age-old theories about the relationship between mind and body.

Some have called this a meta detective trilogy, and indeed books (those already written, those in the process of being written, those being passed from hand to hand) appear on many pages. Adaf refers to the trilogy as “the chronicles of Elish Ben Zaken” (the protagonist), channeling the religious texts that figure strongly in Take Up and Read. Works by Edgar Allan Poe, H. P. Lovecraft, S. Y. Agnon, Alfred Döblin, Walter Benjamin, Arthur Conan Doyle, Jorge Luis Borges, Philip K. Dick, and many works of children’s fantasy populate the trilogy, all but screaming to be noticed and incorporated into our understanding of Adaf’s project. “Genre” as an idea is dissected and experimented upon. Central to the mystery at the heart of the trilogy is a Jewish poet from Morocco named Perotz who, after being captured by the Nazis and sent to Buchenwald, becomes the subject of a typhus experiment. When infected with a certain kind of typhus bacteria, he doesn’t become ill because he’s naturally immune. Nonetheless, his immune system’s reaction to the invader causes a strange change in his consciousness. He starts seeing shadowy figures (which others around him can also sometimes see) and losing time. Later scientists studying this phenomenon believe that such a reaction as this “leaves an opening for study of the structure of reality.”

I focus on this aspect of the trilogy because it anchors the entire story, and it is what I find most fascinating about the work as a whole. Yet it is but a small part explained at the end of the third book. According to Adaf, these are not books in a trilogy but “chronicles,” made up of “the detective novel One Mile and Two Days Before Sunset,” “the meta-detective A Detective’s Complaint,” and “the anti-detective novel Take Up and Read.” Inextricably tied to the events of these books is the music of Dalia Shushan, a native of Sderot (like the author) and one side of the two-person band named Blasé and San Lumière. Her music finds its way into the nooks and crannies of Adaf’s story, passed around via disc, mp3, and human vocals. Channeling her loneliness, confusion, and pain, Dalia’s music outlives her, since her death (under mysterious circumstances) comes while she is still quite young. It is this death that Elish starts investigating at the request of a police detective. Operating outside of official police channels, Elish has bought out half of a private detective agency and usually investigates small incidents—until the Dalia Shushan case is dropped in his lap. A former philosophy student who once wrote a book about the modern Israeli rock scene (with a chapter on “Blasé and San Lumière”), Elish begins uncovering a network of lies, blackmail, and conspiracy involving Dalia, her former graduate adviser, his department boss . . . all the way up to high-ranking Israeli politicians.

I focus on this aspect of the trilogy because it anchors the entire story, and it is what I find most fascinating about the work as a whole. Yet it is but a small part explained at the end of the third book. According to Adaf, these are not books in a trilogy but “chronicles,” made up of “the detective novel One Mile and Two Days Before Sunset,” “the meta-detective A Detective’s Complaint,” and “the anti-detective novel Take Up and Read.” Inextricably tied to the events of these books is the music of Dalia Shushan, a native of Sderot (like the author) and one side of the two-person band named Blasé and San Lumière. Her music finds its way into the nooks and crannies of Adaf’s story, passed around via disc, mp3, and human vocals. Channeling her loneliness, confusion, and pain, Dalia’s music outlives her, since her death (under mysterious circumstances) comes while she is still quite young. It is this death that Elish starts investigating at the request of a police detective. Operating outside of official police channels, Elish has bought out half of a private detective agency and usually investigates small incidents—until the Dalia Shushan case is dropped in his lap. A former philosophy student who once wrote a book about the modern Israeli rock scene (with a chapter on “Blasé and San Lumière”), Elish begins uncovering a network of lies, blackmail, and conspiracy involving Dalia, her former graduate adviser, his department boss . . . all the way up to high-ranking Israeli politicians.

Only someone deliberately ignoring the small rifts and minor quakes throughout One Mile would read this as a straight detective story. One could choose to ignore those disquieting moments and enjoy the book on the surface, but acknowledging and mentally chewing on incidents like the ghostly manifestations in the thicket near his sister’s house and Elish’s own belief that “for twenty years, [his] memory had been deceiving him, concealing things from him, emerging in all the wrong places” lifts the novel onto another plane. Something more is happening than what we see on the surface. Things and people are erupting, breaking through, somehow. Elish, we eventually learn, is genetically connected to Perotz and several other important people in the trilogy.

Elish is himself a focal point for these uncertainties. His first name, he explains to his friend the police detective, is after Elisha the prophet, since his parents were “obsessed” with the Book of Kings. Like the prophet Jeremiah in Dror Burstein’s Muck, which depicts a Jerusalem at once ancient and modern where Babylonian kings in helicopters send the Jews into exile via trains, Elish is bound by his name to see that which others can’t and warn people about what they can’t accept. After uncovering the truth about Dalia Shushan’s death, he becomes drawn into investigating the brief disappearances of two women in A Detective’s Complaint, one of whom his enterprising teenage niece knows and the other he heard about while in the hospital for an auditory illness. The narrative jumps back and forth between Elish’s stay in the hospital for strange inner-ear problems (which we can later connect to his movement through dimensions) and his experiences at a detective writers’ conference in France. Following a thread only Elish recognizes, the investigation into those disappearances leads him to the disappearance of another woman, whose body he finds in the thicket, that very place where his sister had, in the previous book, sensed an inhuman presence.

Elish is himself a focal point for these uncertainties. His first name, he explains to his friend the police detective, is after Elisha the prophet, since his parents were “obsessed” with the Book of Kings. Like the prophet Jeremiah in Dror Burstein’s Muck, which depicts a Jerusalem at once ancient and modern where Babylonian kings in helicopters send the Jews into exile via trains, Elish is bound by his name to see that which others can’t and warn people about what they can’t accept. After uncovering the truth about Dalia Shushan’s death, he becomes drawn into investigating the brief disappearances of two women in A Detective’s Complaint, one of whom his enterprising teenage niece knows and the other he heard about while in the hospital for an auditory illness. The narrative jumps back and forth between Elish’s stay in the hospital for strange inner-ear problems (which we can later connect to his movement through dimensions) and his experiences at a detective writers’ conference in France. Following a thread only Elish recognizes, the investigation into those disappearances leads him to the disappearance of another woman, whose body he finds in the thicket, that very place where his sister had, in the previous book, sensed an inhuman presence.

Take Up and Read, unlike the previous two books, is narrated in large part by Nahum Farkash, a character who appeared only briefly in A Detective’s Complaint. He seems strangely involved in many aspects of Elish’s life, but on the margins. An orthodox Jew deeply learned in religious scripture, and also of Moroccan descent, Nahum actually knew Dalia in person and was deeply influenced by her. It’s almost as if Nahum and Elish have been living similar lives on different planes . . . but I won’t ruin it for you.

As one character bitterly notes in Take Up and Read, the tragedy of the Holocaust, with its barbarism and depravity, came over to Israel with the refugees of eastern Europe. It hangs over their descendants, seeping into the life of every Israeli and keeping the many social and political hostilities at a constant simmer. And yet, as Adaf has declared in the form of the Lost Detective Trilogy, we are all connected across time and space. Other realities might and likely do exist, technology will only force us to understand ourselves more, and the true detective is one who follows an investigation wherever the clues may lead.

Rachel S. Cordasco

Madison, Wisconsin

When you buy a book using our Bookshop Affiliate links on this page, WLT receives a commission. Thank you for your support!