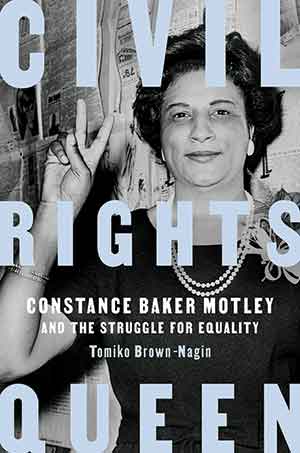

Civil Rights Queen: Constance Baker Motley and the Struggle for Equality by Tomiko Brown-Nagin

New York. Pantheon. 2022. 512 pages.

New York. Pantheon. 2022. 512 pages.

CIVIL RIGHTS QUEEN begins with a provocative poem, written by a fifteen-year-old Constance Juanita Baker, that questions the injustice she experiences as a young child. She writes, “Man made the slums where I live / with its mountains of sin; They jammed the houses together / To keep beauty from entering in.” The evocative poem titled “Listen Lord – from the Slums” begs the question, How does an adolescent African American girl in 1937 possess the acuity to give substance to her surroundings?

Author Tomiko Brown-Nagin adroitly begins her work with the poem as if to suggest that Baker Motley was fated to become a civil rights queen. The genius of the work is the author’s ability to not only rescue Motely from obscurity but to make her relevant in today’s academic, political, and social climate. In her early twenties, Motley tirelessly advocated for her community in the turbulent era following World War II when the reign of terror directed at Blacks continued. Anti-Black terrorism, begun in the 1880s, continued unabated during and especially following the war years as Black veterans demanded resistance to a government that rivaled Adolph Hitler in its persecution of its Black citizens. Brown-Nagin asserted that “she wielded the law like a sword of justice.” But she, like many other women of the time, fell into obscurity. Her mentor and colleague Thurgood Marshall brought her onboard the NAACP legal team, and they crated “a new type of legal doctrine—civil rights law—and laid the groundwork for the landmark changes of the era.”

Brown-Nagin discovers Motley while researching her book Courage to Dissent: Atlanta and the Long History of the Civil Rights Movement (2011) and devoted a chapter of that book to her. According to Brown-Nagin, “in Western societies, historical significance is coded male. The lives of men are deemed worthy of study and remembrance.” Women, when they are included, often are a footnote to men. Brown-Nagin heroically rescues Motely from obscurity in this work. And her efforts are laudable. Civil Rights Queen is quite simply a great read.

Organized into five parts—beginning with her early life and influences and ending with her reign on the bench as a federal judge, Brown-Nagin well documents the story that answers the reader’s curiosity about the fifteen-year-old who wrote the provocative poem that opens the work. Part 1 covers her beginnings through her graduation from Columbia University Law school and her marriage to Joel Motley. Along the journey, the author regales us with lessons on African Caribbean and African American relations, on Depression-era America, and lessons in the norm of sexual harassment in midcentury America.

Part 2 chronicles her work with Fund Inc.—her first case and advocacy for herself. The author’s treatment of the devaluing of Black women during the modern civil rights movement and the so-called work-life balance are invaluable. Brown-Nagin’s interrogation of the standard bearers of the civil rights movement and their transgression against the “norm” is both balanced and enlightening.

Part 3 of the work presents exciting narratives of historical events. It chronicles the challenges, the losses, the wins, the reversals, and the wins again in a dizzying yet provocative way. It also presents insights on historical figures and her association with them. Brown-Nagin is at her best when she articulates the full stories and includes women who were otherwise relegated to footnotes. From the road to desegregating the University of Georgia to the Ole Miss saga to the Birmingham campaign, the author humanizes events. Motley is present and often in the forefront, but she is not alone. There is a celebration of the community that achieves success in this work, as opposed to the traditional hero-worshiping.

Part 4, titled “A Season in Politics,” chronicles Motley’s meteoric rise through the New York State Senate, where she has the distinction of being the first Black woman to hold a seat, to her ascension to the presidency of the borough of Manhattan. At age forty-three, she led the nation’s most populous city and earned a salary of $35,000 a year. From there she accepted Lyndon Baines Johnson’s appointment to a federal judgeship. Along the way, she endured dissections that are part and parcel of female leadership—in spite of claiming not to be a feminist.

Part 5 chronicles her challenges and achievements as a federal judge in the US District Court for the Southern District of New York. Appointed by LBJ in 1966, she was confirmed after a seven-month delay during which allegations of communism and covert affiliation swirled within the ranks of those who opposed her. She was never appointed to a higher court (federal appellate court or the US Supreme Court) because Brown-Nagin believes that her career “hit a roadblock that illustrates the broader dynamic of exclusion amid access in her life, and the ongoing challenges faced by outsiders.” Her legacy to the modern civil rights movement, prisoners’ rights movement, and women’s rights movement, among others, should be well remembered in spite of obvious limitations placed on Motley’s career because of her status as an outsider—Black and female.

Brown-Nagin’s work is well researched, well written, provocative, and insightful.

Adele Newson-Horst

Morgan State University

When you buy a book using our Bookshop Affiliate links on this page, WLT receives a commission. Thank you for your support!