“What It’s Like Here and Now”: A Conversation with Egyptian Writer Basma Abdel Aziz

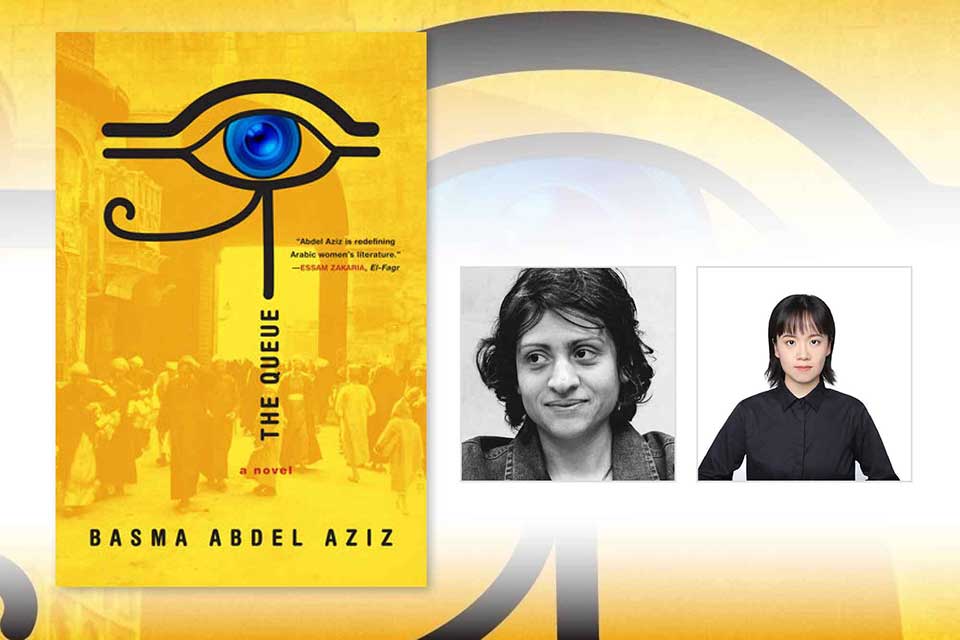

Basma Abdel Aziz is an Egyptian author and psychiatrist recognized for her fictional works al-Ṭābūr (2013; Eng. The Queue, 2016; reviewed in WLT) and Hunā Badan (2018; Eng. Here Is a Body, 2021; reviewed in WLT), as well as her sociopolitical essays, including “Ighrāʾ al-sulṭat al-muṭlaqa” (2013; “The Temptation of Absolute Power”). Her novels are considered representative of Arabic dystopian fiction, which has proliferated in the past decade. Her story “Scenes from the Life of an Autocrat” appeared in the Dystopian Visions issue of WLT (March 2017).

Linyao Ma: Your latest novel, Here Is a Body, was published in English last year. Could you talk about your inspiration for the novel?

Basma Abdel Aziz: My second novel, Here Is a Body, follows two parallel lines. The first one talks about a camp where homeless boys, who have been kidnapped, are trained in a military way to attack others, and they are subjected to the reshaping of their consciousness and ideas, making them loyal to the system and the authorities. This is an imaginary line, and I was inspired by some news and statements that came from journals discussing how these boys and adolescents should not be left in the streets, they should be taken and raised and educated in a military way so that the country could benefit from these boys. From the statements that I read throughout two years, I was inspired to follow this line and create the world of the camp.

The second line is the Space, in which people are holding a sit-in because the ruler, or the president, was kidnapped and there is a coup in the country. Actually, this is not a totally imaginary line. As you know, there was a big massacre here where people at a sit-in were attacked and a number were killed; more than a thousand people were killed. So, this is a reflection of what I saw and a reflection of the testimonies of people I met and heard from about the evacuation of the sit-in. So those are the two parallel lines and how I was inspired to write about them.

Ma: Similar to your first novel, The Queue, this one is also set in a placeless, timeless, and not identifiable location. However, there are still clues or elements that suggest that this place is Cairo. How would you interpret that?

Abdel Aziz: When I was writing The Queue, I chose to make it placeless, if I can say, without a specific time, because I believe that this state could happen anywhere there is a dictatorship or an authoritarian regime. People are manipulated by the authorities and have to wait for each single, very minor detail. I wanted to make it a universal state that was not limited to Cairo, not limited to the developing world. After publishing The Queue, people from the US contacted me and said seeing people under this strong [Donald Trump] administration, it was like it was written for them, not people in Cairo or other places. I love this, actually, because you can see this in places all around the world. It’s not specific to a certain country, and it can happen in many countries.

Ma: As we are talking about this universal state, are you inspired by other comparable novels, such as al-Lajna (1981; Eng. The Committee, 2001), by Egyptian writer Sonallah Ibrahim? Do you think that there are references in your novels to theirs?

Abdel Aziz: I love Sonallah’s The Committee. It’s one of my favorite novels. The similarity was actually from this nightmarish state. People here and there in the two novels, they live in a continuous and endless nightmare. This state of unpredictability, of uncertainty, of what may happen and may not happen, I guess. The novel by Sonallah Ibrahim is a very good one. As I loved it, I also loved those by George Orwell and Kafka. The similarity between all these is the nightmarish situation and how the [writers] put it and how they respond to it.

Ma: Do you see yourself in some of the characters in the novels?

Abdel Aziz: In The Queue I find myself in “the lady with the short hair,” I guess. She represents me. She was trying to resist, to fight even with minor tools. I liked her, and I’m doing what she was doing. In Here Is a Body, I find myself very close to Rabie, the one who keeps asking questions, who wants to examine everything, who does not know the situation so clearly, and who wants to find out facts. He has no certainty, like his friend Youssef, nor is he as mean as Emad. He is the one who wants to experience life, judge everything, and pose many questions to find answers that he may not find. At least he is trying and he keeps trying, so I love Rabie myself.

Ma: I find Rabie al-Mahdi’s name quite interesting. Rabie is literally “the spring” and al-Mahdi is “guide,” meaning “one who guides others to the spring.” Did you name him that on purpose?

Abdel Aziz: Yes. Lots of names in the novel Here Is a Body were included on purpose. You will find that many characters in the line of the campus are named ʿAbd, which means slave. All of them are sort of connected to the authorities, serving somehow in the role of a slave, so I included all of those [names] on purpose.

Ma: About the names in Here Is a Body, the kidnapped boys are called badan, meaning a body, while their superiors are named raʾs, a head. Did you intend to put them together, a head and a body, to form a human being?

Abdel Aziz: In fact, I decided to make all the boys bodies because this reflects how the authorities are using them, they are bodies and have no heads so they have no right to think or to make decisions to refuse or to disobey their orders. Heads represent the authorities as they are the ones who have the right to give orders, obey, punish, and give rewards, while the bodies are perceiving, just perceiving things. Heads are the thinkers who control everything.

Ma: As you keep underlining the state of people living under dictatorship and both of your novels have tragic endings, I would like to know more about how you ended your stories. Some readers consider The Queue’s ending an open one because they believe that Dr. Tarek was capable of changing the fate of the injured protagonist, Yehya. It seems that he was about to make a difference. Are you trying to find solutions or give people inspiration and hope to survive by writing novels?

Abdel Aziz: The ending of The Queue was actually not that clear for many people. You are talking about hope given by the doctor, but some people contacted me after reading it and asked me why I killed Yehya at the end of the novel. They perceived the ending as Yehya died and the doctor just closed the file. I wanted this ending to be open and to let people ask whether Yehya was going to live or if he had died. At the same time, there are other characters in The Queue who gave hope, like Amani. Her state had been improved and she was going to resist. There is a journalist and a doctor who realized, even though it was late, and chose to carry on with the surgery. So, the hope is in other characters and does not necessarily come from Yehya.

For Here Is a Body, maybe the ending is much more violent and abrupt. But still, there is hope. I can see it in two characters. Saber, the man who took Halim with him. A Muslim man with a Christian boy. He did not accept the boy throughout the novel, but his son died and Halim was his closest friend. He chose to forget about the boy’s religion and decided to take him home to raise him and consider him his son. Maybe when he grew up he would start a new life somehow, after all he had witnessed. Yes, there is hope in this ending. Even if it’s violent. For me, I am actually optimistic.

There is also hope in the people who have survived the sit-in. They started to reorganize themselves to resist; even though there was security harassment, they still tried to connect with one another, to enlist those who were lost in the evacuation. You can always see hope somewhere.

You can always see hope somewhere.

Ma: Did you have an expected readership when you were writing the two novels? Egyptian readers or Arabic-speaking readers? Or do you write for every possible reader worldwide?

Abdel Aziz: Actually, when I write, I write for myself in the first place. I do not think much about who is going to read [the novel]. I just write because I can’t stop writing. I do not worry about how I will publish it or if there is going to be security harassment or if the publisher will refuse it for being scared that something is going to happen. I don’t keep myself busy with that stuff. I just write because it’s what I want to do. This is why I can’t say whether I was thinking about who was going to read it.

But let me also tell you that when I was writing Here Is a Body, my motive was actually to document what I had witnessed. There are things that should not be buried, things that should just be documented for people to know about them when the time comes, even after years or decades. This is one of the biggest motives for why I wanted to write Here Is a Body. This is why I recorded many testimonies, and this is why I put a lot of details in the line of the sit-in. These have truly happened. Who is going to read it? I hope everyone, but it is not something to worry about for me.

Ma: As for “Arabic dystopian” novels, my current work is based on that genre. I have read about twenty novels, but you and Kuwaiti writer Buthayna Essa are the only two women writers who have published on this topic, and all the other writers are men. Do you consider that there is an obligation to pay more attention to the gender aspect?

Abdel Aziz: Well, first I do not so strongly agree with the classification of dystopian or nondystopian, because both my novels, The Queue and Here Is a Body, are talking about what it is like here and now—it is not a futuristic point of view, it’s not like imagining what the world will be like here in our country. So, when I was writing my novels they were not dystopian in my mind. I was surprised by the classification. And for me, I don’t intend to put more women in my novels nor to give them a positive image on purpose. It’s spontaneous. Because I’m watching this every day, I’m watching women from low social classes working every day to support their families and their husbands who are not working and take the money for their own pleasure somehow. It just comes spontaneously.

When I was writing my novels they were not dystopian in my mind. I was surprised by the classification.

Ma: I do recall from Here Is a Body the scene where women are marching on the street in the Space and calling on other women to join them. They formed, in the end, quite a large crowd. I found that fascinating. Did that come from reality?

Abdel Aziz: It happened in reality, you know. It happened naturally. I have witnessed it many times myself, and I have cheered it on. It’s not my imagination nor my hope to have strong women. They are strong themselves. They are supporting everyone around them.

Ma: In Here Is a Body, after the “Dusty Cake” chapter, many of those who survived are widowed women who try to carry on the protest. Is that also from reality?

Abdel Aziz: Yes. After the evacuation, there were many groups searching for people and looking after other orphaned children and widows. There were groups like that. I haven’t seen them, I didn’t know them, but I heard about them and I am pretty sure about it. It’s from reality. It did last for a long time. There were women and young people there after the event.

These women are representing hope. They are examples of how to resist, and how not to lose everything.

Ma: Were they like Saber and Halim? Were they characters embodying the continuity of hope?

Abdel Aziz: Of course. These women are representing hope. They are examples of how to resist, and how not to lose everything. If there is hope in Saber and Halim, there is hope in other survivors, in the women trying to resist extremely violent attacks.

March 2022

Basma Abdel Aziz is an Egyptian writer, psychiatrist, and human rights activist. She is best known for her novel al-Ṭābūr (2013), which appeared in English (The Queue) in 2016, translated by Elisabeth Jaquette. Her latest novel, Hunā Badan (2018), came out in English (Here Is a Body) last year, translated by Jonathan Wright. Abdel Aziz was awarded the Sawiris Cultural Award, and The Queue won the English PEN Translation Award in 2017. She is one of the most read and studied Egyptian writers of her generation and one of a few women writers who have participated in post–Arab Spring dystopian writing in Egypt.

Basma Abdel Aziz is an Egyptian writer, psychiatrist, and human rights activist. She is best known for her novel al-Ṭābūr (2013), which appeared in English (The Queue) in 2016, translated by Elisabeth Jaquette. Her latest novel, Hunā Badan (2018), came out in English (Here Is a Body) last year, translated by Jonathan Wright. Abdel Aziz was awarded the Sawiris Cultural Award, and The Queue won the English PEN Translation Award in 2017. She is one of the most read and studied Egyptian writers of her generation and one of a few women writers who have participated in post–Arab Spring dystopian writing in Egypt.