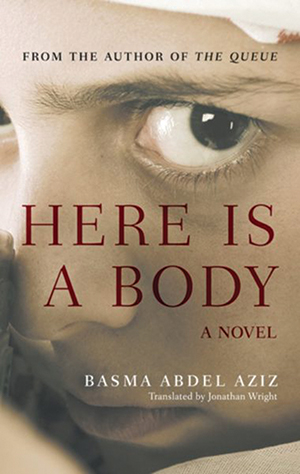

Here Is a Body by Basma Abdel Aziz

Cairo. Hoopoe. 2021. 333 pages.

Cairo. Hoopoe. 2021. 333 pages.

IN HERE IS A BODY, Basma Abdel Aziz’s follow-up to her acclaimed, award-winning novel The Queue (WLT, Sept. 2016, 73), a coup has overthrown the unnamed ruler of an unnamed Middle Eastern nation with an Islamic majority, which one might assume to be Egypt. The supporters of the absent ruler and the usurping military regime are each trying to gain control of the country, and the masses are but disposable tools in that endeavor. The ambiguity of location and temporality also underscores the universality and repetition of such political cycles.

Via a deft translation by Jonathan Wright, Abdel Aziz employs dual narratives in alternating chapters that overlap near the end of the book. The novel starts with a series of abductions of impoverished and mostly abandoned street children. We meet a number of boys, at the outset, though Rabie acts as our primary guide. He is initially separated from his friends, ending up at one of the “rehabilitation” centers of the “System,” led by the generals who have taken over the country. He becomes one of many “bodies,” as the masses of boys are called, compared to the “heads” that run the program. What happens when you become—and believe you are—only an appendage?

Knowing that and how this reprogramming is happening with these young teens doesn’t make it any easier to witness it. Separate them, terrify them, make them believe their captor is their savior, one feels their furls of identity and individuality fold, and shrink, and die away, the same way the sun sinks into the horizon in an instant, leading to darkness. It’s that easy, and that quick, that horrific.

Inside the “Space,” the deposed ruler’s supporters—the Raised Banner—live in an idealized bubble, ironically shown primarily through ophthalmologist Murad and his wife, Aida’s, perspectives as apolitical sympathizers who have come to take advantage of employment opportunities. Sensitive and thoughtful Aida initially goes back and forth between the other part of the city where her family is and the Space but soon becomes part of the community and a teacher to the range of young people living there.

Early in the novel, the General says that all that is expected of the conscripted—read: kidnapped—boys is “trust, honesty, obedience, and loyalty.” It’s no surprise that this is the language of family and long-standing friendship. It’s something these boys lack, and want desperately, and the System—the current ruling class—knows exactly how to garner it, through carrot and stick. Much the same is happening in the Space, under the opposition Raised Banner. In their sterile, seemingly perfect bubble, there’s a similar sanitization of narrative, free and plentiful food, face-painting for the children, and entertainment for the adults: almost a vacation-like environment. They too are “bodies” if not named so directly, equally disposable as we learn later. In both environments, people are controlled through rhetoric, media, religion, and even the quality and quantity of food that’s presented. Socioeconomic differences also create subtle nuances that further separate individuals when the System and the Space come into inevitable conflict.

Abdel Aziz explores the deepest aspects of what it is to be a human being: If you can’t trust your own eyes, friends, history, and memories, who—what—do you become? How do you navigate the world, and how can there not be permanent damage done to the psyche of a society, regardless of political stance? “One rehabilitates us and one terminates us,” says Rabie, and the blurred lines of who the “one” is in this novel reflect the unsteady ground for all those in totalitarian states.

The disappearances on both sides—children, protesters, the deposed ruler, even individual names—indicate how appallingly easy erasure is, with endless refills of bodies available to feed the power machine. This ersatz dystopian novel is all the more impactful because it doesn’t feel removed from what we watch in the news or experience personally. The inevitable conflagrations at the end of the book are no less disturbing for the knowledge that such manipulations and disasters will continue, and that we are complicit by choosing to live within the illusions of our own bubbles. Names and locations may be superfluous in a world of soulless governments and capitalistic opportunists, but in Here Is a Body, Abdel Aziz stirringly shows us, and demands of us: to witness, name, and remember.

Mandana Chaffa

New York