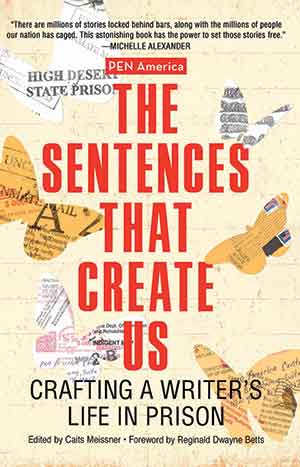

The Sentences That Create Us: Crafting a Writer’s Life in Prison by PEN America

Chicago. Haymarket Books. 2022. 328 pages.

Chicago. Haymarket Books. 2022. 328 pages.

EDITED BY CAITS MEISSNER, current director of the PEN America Prison and Justice Writing Program, The Sentences That Create Us is a welcome revision and expansion of the classic Handbook for Writers in Prison. Essential for all incarcerated writers or volunteers/mentors working with incarcerated writers, highly recommended for all writers, and an interesting read for everyone else, it comes along at the right time given the two million people locked up in US prisons and jails, a 500 percent increase over the last forty years, and the growing public awareness of deep faults and injustices in the system.

While the Handbook provided the blueprint, this anthology, which is three times the length and draws on decades of experience, builds the house. Four prefatory pieces provide foundational context for prison and justice writing in the US, and the four parts—Foundations of Creative Writing, Crafting a Writer’s Life in Prison, On Building Writing Community, and Writing Exercises—provide plenty of diverse spaces in which one can find suitable instruction and inspiration. Randall Horton’s excellent epilogue functions like well-placed skylights over the whole collection, and the “Further Resources” section, eight pages of publication venues for incarcerated writers, is as solid and useful as a well-designed study. Also, every piece in the anthology is written by someone currently or formerly incarcerated, or a volunteer who has experience working with such writers, which means it’s all real talk, and many of the stories and voices are unforgettable.

For example, Mitchell S. Jackson begins his piece titled “Re-Vision”: “Let me tell you how I got popped. Let me start with a couple of hours pre the arrest, when I was in medias res cooking dope in the house I shared—a blatant disregard of her wishes—with my then girlfriend.” And while it takes two pages for him to get to the writing advice, it hits when he does: “Revision is discovering what’s right and imagining how to make it more right; it’s pursuing a new way of seeing and being. Revision is a philosophy; revision is revolution.” He then deftly moves back and forth between memoir focused on friends lost to violence and practical advice on revising. This marriage of hard-knock, often devastating stories coupled with no-nonsense writing, publishing, and community-building advice marks most of the pieces.

Other standouts include “On Journalism,” edited by Jaeah Lee with interviews and research by Kate Cammell, which incorporates interviews with incarcerated writers who have started newspapers and even podcasts on the inside; “The Price of Remaining Human,” by Thomas Bartlett Whitaker, who spent eleven years on death row in Texas while enduring 161 fellow inmates being executed, and who testifies to the endless difficulties caused by being a writer in prison yet argues for its importance; “Burn the Spot,” by Piper Kerman, author of Orange Is the New Black, who muses on the need to tell the truth despite survival habits that push the other way; and “And Still I Write,” by Alejo Rodriguez, who discusses the importance of voice and agency despite and above all else. Also notable are “Start and End with the Feeling of Home,” by Louise K. Waakaa’igan, who describes the path to publication of her first chapbook and what she learned along the way; “On Writing and Staging a Play in Prison,” by Sterling Cunio, who documents the creation of his historical drama and its production via Zoom with the use of actors on both the inside and outside; and “No Pen or Paper Required,” by Casey Donahue, who outlines how to create not a safe but rather a brave space for community storytelling.

While practical and instructional, this anthology is ultimately about the redemptive power of language, especially creative language, and its ability to shape and reshape our worlds, both individual and collective. Meissner’s “Editor’s Note: How to Read This Book” ends, “No matter where you stand (or sit, dedicated at your desk), this book can teach you not only how to improve your writing but also how to be more fully human if you let it.” In my experience working with writers at the Joseph Harp Correctional Center in Lexington, Oklahoma, prison and justice writing leads to a sense of voice and agency for those trapped inside an often unjust and dysfunctional system. For those on the outside, it provides a better understanding of them as individuals and provokes a willingness to try to fix this system. In this way, we can all become more fully human if we want.

Timothy Bradford

University of Oklahoma

When you buy a book using our Bookshop Affiliate links on this page, WLT receives a commission. Thank you for your support!