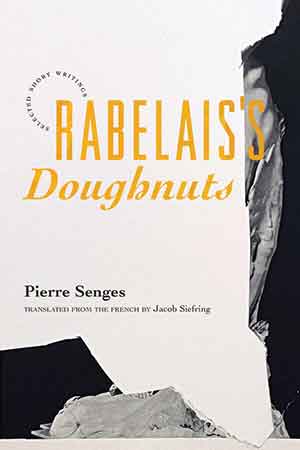

Rabelais’s Doughnuts: Selected Short Writings by Pierre Senges

Seattle. Sublunary Editions. 2022. 124 pages.

Seattle. Sublunary Editions. 2022. 124 pages.

AS A NOVELIST, Pierre Senges is generally published by Verticales, one of the two mainstream purveyors of experimental French writing. Senges epitomizes the Verticales house style: his prose manifests all the hallmarks of what has come to be known as postmodernist or poststructuralist literature. It’s constantly on the move, punning and playful, whimsical and grave within the same sentence, wide-ranging and narrowly focused, euphonic and discordant, rational and open to sentences that invite a cognitive conundrum. The manner of these pieces is closer to Derrida than it is to Terry Eagleton, so Senges’s collection is not for the reader seeking a fast, easy read.

Collected from several literary magazines, the seven miscellaneous essays that make up Rabelais’s Doughnuts meditate and riff on subjects as diverse as the contemporary literary market, Renaissance art, libraries, and style. A significant number of these prose pieces bridge the boundary between creative writing and essayistic composition, fitting comfortably into neither. The French concept of the exercice de style as illustrated by Raymond Queneau describes them best.

The first piece in the collection is entitled “Suite”: it duly follows the fourteenth-century thematically and tonally linked series of musical modes, a structure masterfully illustrated in Isabelle Dangy’s latest novel, Les nus d’Hersanghem. The main subject of this piece emerges from the meandering, digressive, multireferential text as the French genre called “autofiction” (autobiographical fiction foregrounding the author in fictional situations). As certain satirical remarks suggest, Senges is no lover of this mode: “With a little luck we’ll be able to exorcise the me-and-my-era, the me-and-the-world-seen-out-my-window, the me-and-my-opinions, the me who is a victim of indignation at the hands of everything and everyone (proof of its plasticity there), the me-and-my-fate-and-my-style, the me-and-my-

book-currently-being-written, the me-and-my-heroic-drunkard’s-gourd-preserved-in-eau-de-vie, uncorked on special occasions.”

It’s a lively, humorous send-up of the contemporary literary market but tends to overestimate the dominance of the market by autofiction: it’s a common French gripe amongst some literary editors who can’t wait for this forty-year-old trend to end, as if autobiographical fiction was a recent phenomenon that was ever going to end. I would also question the dominance of it on the French market, which seems much more oriented toward what the French call “exofiction,” the fictional portrayal of historical figures.

Much of the animus against autofiction seems at least partially focused on resentment toward the autofiction novelist Christine Angot for her mordant evaluations of other writers on the television show On n’est pas couché. She recently received the Prix Médicis for Le voyage dans l’est, crystallizing fears that the genre of autofiction is here to stay.

The second piece in Senges’s collection, “Last Judgment (detail),” features a discussion of Daniele da Volterra, who was requested to paint clothes over some of Michelangelo’s nudes. It’s a playful, digressive, anticlerical representation of the artist’s feelings as he paints over the masterpieces. It ends on a fanciful note, imagining future priests denouncing “the ignominy of genitals clothed.” Michelangelo makes a comeback in another of the pieces in the collection, this time in a dramatic monologue voiced by another minor artist, Pierre Aretino.

“A Slightly Vain Exercise in Style” takes riffing to a whole new level, illustrating its title in a self-knowing way that takes the reader right into the heart of the Barthian funhouse. “On the Electrophorus and the Tohu-Bohu” pursues in this vein, taking a brief article by Heinrich von Kleist apart in minute detail. It’s an exercise in slippery deconstruction that would no doubt have delighted Derrida himself.

Toward the end of the collection, “Many Ways to Stuff a Watermelon” shows us Senges at his most whimsical. The piece focuses on increasingly bizarre and sometimes imaginary libraries belonging to the likes of Jean Paul Richter, Maria Wutz, Sigizmund Krzhizhanovsky, Giacomo Casanova, Bouvard and Pécuchet, to mention but a few. One is put in mind of Borges’s reeling eclectic outreach and the zany world-juggling of another sometime-Verticales author, Claro. “The Counterfeiter” is another dramatic monologue staging a banknote forger who takes great pride in the execution of his art, offering it to the reader in a poetic, philosophical mode of aesthetic appreciation.

All in all, it’s a bit of a roller coaster of a read that has both gravitas and sprezzatura. Although it requires a good deal of concentration, it’s a pleasant break from lightweight commercial fiction and the usual considerations of the literary market. As Senges puts it when discussing Émile Borel and Arthur Stanley Eddington’s library, “exhaustivity in writing is a dream or a nightmare wrought in the Pécuchetian style.” The whirling ramble of Rabelais’s Doughnuts is more like a kaleidoscopic dream.

Erik Martiny

Paris Sciences et Lettres