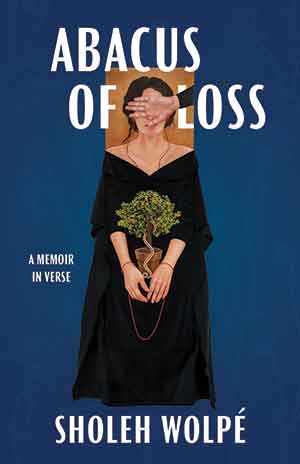

Abacus of Loss: A Memoir in Verse by Sholeh Wolpé

Fayetteville. University of Arkansas Press. 2022. 124 pages.

Fayetteville. University of Arkansas Press. 2022. 124 pages.

ON THE OPENING PAGE of her newest collection, Abacus of Loss: A Memoir in Verse, Iranian-born poet Sholeh Wolpé shares an image of a classic abacus. Below it is the statement: “The abacus is an instrument of remembering.” But unlike the ancient abacus, Wolpé’s abacus does not calculate numbers but, rather, a multitude of beingness. As the organizing principle of her memoir, it neither subtracts nor adds but simply makes a tally in a language (“loss is a language / we all speak well”) that helps us get at the poetry of making, living a life, and having it add up to something.

In what seem to be arbitrary snippets of time, episodes over a lifetime of events, locations, and people, we learn of the travels and travails of a girl who begins life in a country called Iran and traverses continents until she finds herself a woman in another. In Persian-numbered chapters 1 through 10, Wolpé takes “account.” It is a life of movement, change, loss, and renewal. Rather than titling each poem, she simply assigns each poem in each of the ten chapters with the heading “Bead,” followed by a number. This calculus of remembrance is much more about what the poet/speaker chooses to remember than what has defined each part of her life. Even while Wolpé titles her book “a memoir,” she does not allow us to believe in the ordered chronological nature of how a life unfolds, nor of how it is remembered. It is a sum of events, experiences, losses, and gains. After Bead 1 opens with a prose segment, she offers us this:

That we choose the color

of our loss, like a blue

sash draped across

mourners’ black. That

eyes follow blind

towards the cobalt moon,

will slant us over and

down, crooked toward

mud on our graves.

Blue becomes the color of a body. A body of knowledge. A body of thoughts. A body of . . . At the bottom of this opening page, Wolpé writes a series of poetic short statements in Persian that are untranslated: “my eyes are blue, my face is blue, my hair is blue, my blood is blue, my thoughts are blue, my soul is blue, my sigh is blue, my hands are blue . . .” It is a kind of mantra to frame our reading, signaling that like the words on the page, we eventually fade to nothing. But in between the beginning of the “slimy pink ooze” that she questions as the origin of our beginning, and the fading to blue, there is so much else.

In Abacus of Loss, we learn of Wolpé’s earliest childhood memories, including her first punishment when the teacher asks her and her fellow students to list seven pleasures of life. Her list, “an honest list,” gets her sent to the principal’s office for already being transgressive and rebellious. Each section, punctuated by loss, by a remembrance of pain and alienation, by seeking and finding, also offers its shadow—“windfall—how life moves us—back and forth—across time and space”—in a kind of up-and-down movement like the beads on an abacus; one bead stands for an experience, a series of experiences, that cannot fully be understood until time has passed. These passages are made more poignant perhaps against and through the conventions that might be expected of a girl, a woman, a mother, a wife, particularly from a country and culture that closely guards women’s virtue and women’s roles. Wolpé shows us the inadequacy of convention for living a full life.

In her own “exile” of having left Iran as a teenager, first to Trinidad to live with her aunt, and later to London to attend boarding school, Wolpé speaks of the first great loss: childhood. In “The World Grows Blackthorn Walls,” she captures her arrival in the country of her migration, writing of America: “And when I arrived / you punched yourself into me / like a laugh.” But even while she writes, “I never meant to stay away,” Wolpé’s ability to return to Iran grows more fleeting with the revolution, with war, and with the increasing persecution of religious minorities, such as those of the Bahá’í faith, to which her family belongs. But living in another country begs the question: “What is a transplanted tree / but a time being / who has adapted to adoption?”

Even while we see in the calculus of her memoir the omnipresence of loss—of childhood, a country, a niece, a marriage—Wolpé insists on something that connects her to life, and to the poets of her country of origin—Rumi and Hafez—and it is, indeed, a kind of faith. In the final chapter, “The Tally” (Bead 3), the final poem opens: “Listen / nothing’s too small / for gratitude.” Wolpé calls us to listen. It is a memoir of remembrance and loss but also a memoir of wisdom and expansiveness evoked in small beads of intense beauty.

Persis Karim

San Francisco State University

When you buy a book using our Bookshop Affiliate links on this page, WLT receives a commission. Thank you for your support!