W pośpiechu rzeka płynie (Like a rushing river) by Anna Frajlich

Szczecin, Poland. Forma. 2020. 64 pages.

Szczecin, Poland. Forma. 2020. 64 pages.

CZESŁAW MIŁOSZ CALLED Anna Frajlich’s poems cantilenas; Stanisław Gliwa said, “You use the keyboard of Polish language so elegantly and with such sentiment. . . . Your poems are delicate wreaths woven from the sounds of language into a picture of your feelings and experiences, a picture of your heart.” Several decades after these comments, in W pośpiechu rzeka płynie (Like a rushing river), Frajlich continues to craft delicate poems with a miniaturist’s precision. The closeness between Romanticism and classicism is revealed in an exquisite sequence of verses that move seamlessly from one image to another (“Near”). Such economy of words allows aphorisms in which humor alleviates pain—banishment from hell is still banishment—and, in “Definition,” “I hurt therefore I am.” These counterpoints pit the concrete against the abstract when the poet describes the healing touch and smell of the earth during her “Return into the Unknown” (i.e., her 2014 visit to Kyrgyzstan, the land of her birth).

Structured as a thematic diary, the fifty-one poems describe a life journey through the mirror of memory, emotions, and dreams that are in turn mirrored in nature’s perpetual motion: wind, water, and time. This stream of consciousness is marked by the scar of banishment and the double loss of her ancestral cities of Kraków, Lviv, Szczecin, and Warsaw during the Holocaust and the Polish anti-Zionist campaign of 1968. The first section of W pośpiechu rzeka płynie, entitled “Departures, Returns, Memory,” features many unpublished or lesser-known poems. Two of her earliest exile poems, “Tuscany,” written in 1969, and “Seder,” written in 1971, evoke the Christian Eucharist and the Jewish seder, namely, the sacrifice of Jesus and the suffering of the children of Israel, who are overlooked by the prophet.

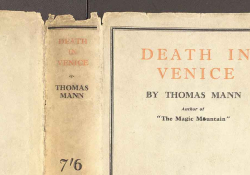

The second section, entitled “They Are Still Reading,” showcases writing, reading, consuming, and analyzing literature. The knowledge provided by books serves as a central reference in the poems. Having espied a young man reading Death in Venice, the poet takes us through the entire twentieth century by the mere evocation of little Tadzio and the great Thomas, then evokes the turning of pages as a sign of the persistence of the printed word in the age of the internet and concludes, with the inversion of the words life and death, that “Death in Venice still lives” (“True Books”).

The third and fourth sections constitute the last third of W pośpiechu rzeka płynie. “Searching for the Key” is a veiled evocation of the fall of humans from the Garden of Eden (“Back from a Trip into Adulthood”). “To live in eternal sleep” focuses on the approach of death. Sleep and death are interchangeable: “To die while sleeping / weightlessly / to slip unnoticed / from one dream / to another / to only dream / and wander / through sleepy labyrinths / into the infinite / to live in eternal sleep” (“Sleepiness”).

The journey ends on a vanitas vanitatis note and with a vision of our eternal home: “Slowly our graves / take root in the earth / someone threw us here / like a stone / and where we were / dust will remain / gold as the golden autumns of yore” (“Dust”). With lullaby-like repetitions, alliterations, and softness, Anna Frajlich invites us “to start looking / for the time / that passed / and the day / that faded.” Her search for an impossible return concerns all of us.

Alice-Catherine Carls

University of Tennessee at Martin