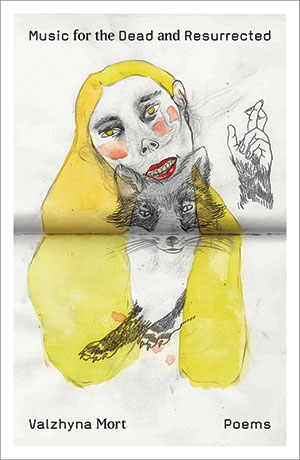

Music for the Dead and Resurrected: Poems by Valzhyna Mort

New York. Farrar, Straus and Giroux. 2020. 112 pages.

New York. Farrar, Straus and Giroux. 2020. 112 pages.

VALZHYNA MORT’S VOICE FEELS as if it survived a poetic conflagration. There is an imprint of crushed existence—charred bones and like detritus—within which, startlingly, there is also survival, intact. The voice in these poems carries into its own afterlife—which is our world—a strangely deepened certainty: that the act of composing poetic truth matters, even if nearly all else from before has retracted in the postapocalyptic glare. This is the spirit of her poems.

This process of coming back is also, in this case, a process of coming here—to the English language. Like other poets washed onto US shores with their ethics intact in our recent collective past—Czesław Miłosz comes most readily to mind—the path toward poetic wholeness is also a process of aligning one’s cultural heritage, identity, language, and concerns in a renewed frame. The poem “An Attempt at Genealogy” begins: “Where am I from? // In black basilicas / dragged incessantly / down a cross / is a man / who here resembles / a dress // snatched from a hanger, // there: thick clouds of muscles— / an overcast body— / embodied weather / of one hardly known country. // (A country where I am from?)”

These are not poems of redemption, yet they work in a space where redemption is possible—albeit unacceptable unless and until it is real. Such insistent authenticity may be especially valuable when so much of our forms of living have been slyly emptied of value and function:

Verily, in Your image: I hover

in the glory of fish shops,

in the chlorine of classrooms.

In my stomach is the midnight

of bread.

Especially since Belarus has been foregrounded as a topic in recent months, the voice in these poems provides some connective thread in our understanding of what such a configuration can mean not only sociopolitically—as proffered in the news relentlessly—but also in the inner life, with its deeper implications of what has “really” happened, and how one can possibly navigate from here.

“Since then, many birds are shed / across the air. / The dents on cups gag many thirsty mouths. // What has been done to us is muddled with the fears / of what could have been done. // Our famous skills / in tank production / have been redirected / at students and journalists. // But under that roof, folded / like a dead man’s hands over the house, / we still live.”

Such poetry—such threads back through the real—holds forth promise in turn that we can connect forward as well. Perhaps this is ultimately why we gravitate so strongly to such thin, frail threads of actual humanity as one finds on offer in these uncompromising poems: that they hold forth the beguiling premise of an unbroken future as well.

Andrew Singer

Trafika Europe