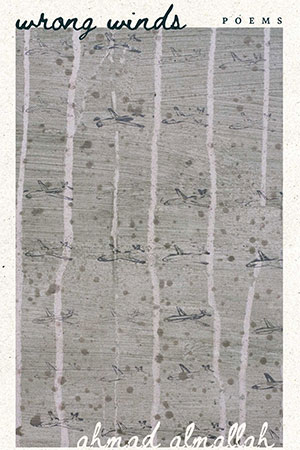

Wrong Winds by Ahmad Almallah

Portland. Fonograf Editions. 2025. 72 pages.

A brief look at the table of contents of Ahmad Almallah’s third book of poems alludes to what may be the cornerstones of his poetic experience: Gaza, Disaster, Land, Tongue, Rebel, Love, Life, Summer, Poet, Andalusia, Afterlives, Lament. After Bitter English (2019) and Border Wisdom (2023), Almallah pursues in Wrong Winds his exploration of the relationship between poetry, language, and different forms of violence, loss, and displacement. Deeply rooted in his wounded Palestinian homeland yet shaped by a constant critical engagement with world poetry, Almallah’s new collection, written in the early months of the ongoing genocidal war on Gaza, continues his investigation of the liminal space between languages, spaces, and temporalities.

A fine connoisseur of classical Arabic poetry, Almallah opens the book with a poem inspired by Al-Shanfara, the pre-Islamic Arab poet best known for his Lāmiyyāt al-ʿArab (L-Poem of the Arabs), a long poem about desert life, exile, and self-reliance, which was analyzed by several grammarians. Faced with the ordeal of Gaza, the poet follows in the footsteps of Al-Shanfara and sets out to confront his deep pain: “this proud bitter self / has no place in it / for injury.” The book, introduced with a quote from Gwendolyn Brooks and dedicated to Gaza, is above all an act of witnessing and reckoning, relentlessly asking questions such as “Where do they find the time / to arrange tragedy on the board, / plot and strategy?” or these ones addressed to his partner, the literary scholar, poet, and translator Huda Fakhreddine: “How would you write disaster when this line is / over? What will you do to prevent it from being / the end?” As is often the case in Palestinian poetry, the act of questioning frequently shifts to more defying statements that starkly expose the indiscriminate destruction of the war: “The best way to solve / your problem is to save time: / eradicate me. / I just don’t seem to add up / to more than a zero on the side / of numerical figures that only / appear to you, when your work is done.”

Almallah’s poetry not only resists the reduction of shattered Palestinian lives to mere numbers, but it also invites the reader to reflect on what writing can truly do in times of extreme devastation: “When the world ends / – as in the now – we’ll / have to turn books to / their source, and use / them as burning wood.” The destiny of Palestinians, the poet reminds us, remains organically bound to their land: “Against the rivers / and their beds, East / and West banks, we mine / the land with nothing / but our feet.” Palestinian identity is forged through endurance and memory, shaped by the burden of the past and the impossible task of fully grasping the present: “only scarps that once in a while / remind us of who we were; never who we are.”

As meaning keeps “repeating itself to / itself” and names become “the first steppings / into ruin,” the poet explores how language grapples with erasure and helplessness. While language is often distanced, disaster is “always at hand”; Almallah’s poetry turns this paradox into an opportunity to reflect on the power(lessness) of words: “I tell you, my tongue / is tied up today, and maybe will / forever be after this and that / genocide.” Poetry here is both lucid and resilient, equally aware of “the fallacies of naming” and of the ruins within which one must invent a new language.

Almallah’s poems convey a sense that words continue to perform their tasks yet remain burdened, steeped in a unique and unresolved tension: “I don’t know mainly how / to save myself from my / words: I would want them / all, alive and well, or at / once, all at once / burning.” The only path forward is through movement between languages, as Almallah intersperses his poetry with scattered, untranslated fragments of German, Spanish, and especially Arabic, unfolding a reflective translingual poetics: “I only – / escape language / to languish in another –” The emergence of Arabic often serves to resist alienation and recover history, though not without a critical lens. In Alhambra, for instance, the poet reads the motto of the Nasrid emirate of Granada yet remains alert to the nostalgic pull of Arabic.

Wrong Winds is a book about how the world has lost meaning, leaving poetry to confront tormenting questions of language and comprehension: “Words overwhelm and say / stop. / We, like the body / can carry / no more.” Sometimes, Almallah dreams of an elsewhere where he can reunite with his late mother and connect with the dead. At other times, he reflects on his own identity, position, and role. In every case, he continues to plant words as seeds destined to grow and bear fruits. Moving between screams and silence, ashes filling the sky and exiles crying for their unfound homes, useless mirrors and ruins speaking to poets who cling to meaning, the book elucidates the difficulty of preserving clarity in a chaotic era while holding onto the values that bind humans together.

Readers familiar with Palestinian poetry will find many resonances with the new generation of poets from Palestine throughout the book. When Almallah asks, for instance, “What does it mean to be a poet, another ‘Homer’ / going home, trying to find one?” one might recall the Gazaoui poet Hind Joudah’s haunting question: “What does it mean to be a poet in times of war?” At the same time, Almallah’s poetry bears the imprint of international poetic influences. For instance, “Holy Land, Wasted,” cowritten with Fakhreddine, is an attempt, as he explains in a concluding note, “to displace” T. S. Eliot’s The Waste Land by “challeng[ing] its Eurocentric currents and plac[ing] it in Gaza now, and in Palestine in general.” Between rewriting and writing back to Eliot, a key influence on several Arab modernist poets, Almallah makes the Palestinian question central to the act of composing and renewing poetry.

Numerous other dialogues and journeys expand the scope of the book. Whether visiting the house of Lorca, invoking the history of Berlin, or describing the eternal, almost unreal beauty of Alhambra, Almallah skillfully combines poetic registers, weaving together lyrical, dramatic, and conversational elements. Echoes of Paul Celan, Emily Dickinson, and Zbigniew Herbert further highlight the simultaneously introspective and dialogic nature of Almallah’s poetry as well as his engagement with themes such as existence, consciousness, and ethical resistance in the face of historical trauma. In the shadow of “the old olives / of Palestine,” Almallah’s poetry is propelled by reverberation: an intricate network of mirroring questions and spaces, a continual effort to reverse perspectives and reinterpret images. The result is a restless and rigorous poetry that remains aware of its duties, sharp in voice, and imbued with an underlying sense of resilience and harmony. To the “wrong winds” of annihilation and dehumanization, Almallah opposes the constantly arising winds of revival and regeneration: “nine / months of murder can’t / cancel a new-born wind / in those wombs that / have failed to carry the / fractions of your numbered / past.”

Khalid Lyamlahy

University of Chicago