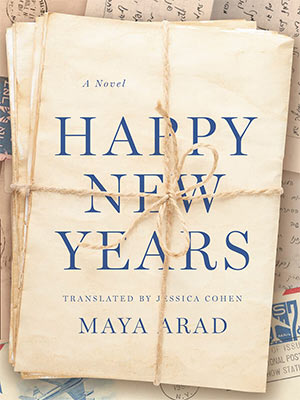

Happy New Years by Maya Arad

New York. New Vessel Press. 2025. 376 pages.

With immigration a timely topic, a new novel by an Israeli writer parses cross-cultural identity via a distinctive approach. Maya Arad’s protagonist in Happy New Years is a humdinger. Leah Zuckerman goes beyond her creator’s assigned task, shining a spotlight not only on migration but also on aging, capitalism, militarism, generational differences, and particularly feminism.

She’s an immigrant in three countries: Romania (birth through age eight), Israel (growing up), and America (as adult Hebrew teacher and realtor). From 1966 to 2016, Leah wrote annual Rosh Hashanah letters to former classmates from a women’s teaching college in Israel detailing her life across the Atlantic.

After she dies, her two sons, Yonatan and Ari, wonder what to do with them. Thus the dispatches end up in the hands of an imaginary editor, Dr. Gavriella Sadan (Sadovnik), with a plea: Could the eminent publisher “do something” with them?

Indeed, she could, warning in the book’s preface that “the letters you are about to read have no literary merit.” Weighing that term in a superb digression, she raises the penetrating question: “Is a text’s literary value determined by its sales revenue?” I was captivated by Arad’s cleverness in critiquing the publishing industry through this marginal character, who states: “If, by publishing these letters, I inspire even one woman to seek out a more sophisticated conception of feminist thought, I will have done my part.”

After Leah escapes the Romanian Holocaust with her parents, she’s mocked in Israel for her “otherness.” Her parents run a small grocery store, illustrating society’s judgment of people by monetary value (an allusion to current asset worship?). When Leah arrives in America, she’s derided again as an immigrant on both the East and West coasts.

Must a writer be from the particular culture portrayed to offer collective insight beyond that country? Arad’s forte is not necessarily eloquent sentences but rather constructing clear character voices, aging Leah subtly through speech. I didn’t visualize Leah as much as I understood her personality. In naïve narcissism, Leah asks resounding questions, almost as if playing roles—each year a new act: the road not taken, the “what ifs” and “if onlies.” Arad captures broad themes felt by anyone acclimating as a stranger in a new context.

Leah portrays a relentlessly rosy life in her letters, throughout romantic relationships, marriage, divorce, raising two boys alone with little money, and establishing a profession. She’s determined her children will grow up speaking two languages to stay connected to their cultural heritage overseas, believing it’s good for their brain development while realizing they’ll view themselves as American.

Arad ages feminism alongside her protagonist as she comes to terms with a definition of self. Leah was late to the “Me Too” movement, but she finally arrived. What to do with those childhood images, though, especially the first eight years? That period of human growth and development is called “formative.” Leah acknowledges being embarrassed her mother was from Romania once they arrived in Israel. Yet at age eight, granddaughter Ella remembers Leah after she dies: “She said her job was to be my grandmother. That was her favorite job.”

Arad’s genius in juxtaposing group letters alongside more personal postscripts to Mira metaphorically illustrates the construction of social media personas versus offline IRL. She captures psychologically how strong public images can exist while offline doubts remain. Leah’s postscripts disclose her innermost feelings, not as rosy as what she depicts to the group.

Leah ultimately believes that “people from all over the world want the same things.” Arad ponders what pulls many immigrants back to their original countries, why some stay and some don’t (if they have that choice). Artfully, Arad points out that even though people may speak the same language, they often don’t—employing dialect differences between Yiddish (Germanic) and Hebrew (Semitic) in a shrewd way, akin to High and Low German or even accents in American English (Northeast versus Deep South).

Arad actually inserts herself into her own manuscript, when Leah turns seventy and takes a creative writing class from her. There Leah realizes, “I’ve never been good at making friends,” noting her Israeli pen pals rarely answer (except for Mira). Leah continues to correspond, though, mentioning differences in America versus Israel, such as packaged cake mixes, pain-free birth, disposable diapers, and paternity leave.

When Leah teaches English as a second language to “poor kids in Mountain View,” she asks five-year-old Marisol to teach her Spanish in turn. Leah easily represents a multitude of issues faced by many who try melting into the pot of a new country but are dismissed.

Her inventor pushes the novel’s form in Happy New Years through the ingenious manner in which she delivers the tale. Maya Arad transcends one country. She can’t be pigeonholed as an Israeli writer after the creation of Leah Zuckerman.

Lanie Tankard

Austin, Texas