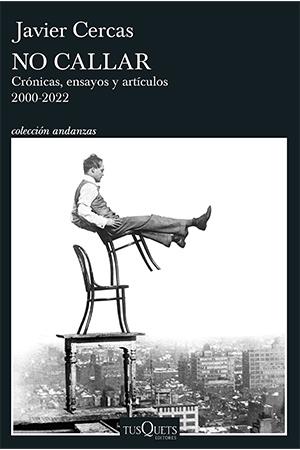

No callar: Crónicas, ensayos y artículos, 2000–2022 by Javier Cercas

Barcelona. Tusquets Editores. 2023. 752 pages.

With the late Javier Marías, Javier Cercas and Enrique Vila-Matas—both relentless nonfiction writers—are the leading contemporary Spanish novelists, the most translated and admired. Cercas, a member of the Royal Spanish Academy, stands out for his no-holds-barred opinions, range, innovative practice, and wit. No callar, a superb miscellany of the journalism, essays, and articles he published between 2000 and 2022, complements the nimbly erudite The Blind Spot: An Essay on the Novel (2016; Eng. 2018), his Weidenfeld Lectures at Oxford.

When fellow Spanish writer Andrés Barba inquired whether other authors of nonfiction novels influenced him, Cercas responded: “I think of each of my books as more of an all-you-can-eat buffet—fiction, essay, crónica, history, biography, autobiography.” In a 2024 Paris Review interview, asked if he feels oppressed by academia, he responds that writing for El País “helped me fuse the philologist and the writer.” The conversations in La aventura de escribir novelas (2024), which include a piece on Hugh Grant and the future of the novel incorporated here, amplify his revisions of Western canons. No callar’s prologue clarifies that, “more than an intellectual or a columnist, I consider myself a novelist,” recognizing he must keep taking sides on the Ukrainian invasion, Brexit, or national populism. Still, “El tiempo de las mujeres,” which opens the collection, registers how, despite Europe’s return to times of war, the great theme today is “the women’s revolution.”

The forensic sensibilities and diverse cultural interests in No callar complicate choosing the finest among the revised and slightly modified 245 texts organized into nine sections. The first four discuss Spain’s reworking of outside influences and democratic contemporaneity, asking sociopolitical protagonists to acknowledge that they brought about the developments they dread. The best is perhaps 2017’s “¿Qué significa hoy ser español?” published in the New York Times. Sections 5–7 show literature’s role in restrictive cultural milieus, as when he writes about or quotes Flaubert, Cervantes, Vargas Llosa, Bolaño, Ortega y Gasset, or Orwell. And Cercas would not be Cercas, or Spanish-language prose’s Martin Amis, without establishing subtle and necessary distinctions between bullying and provocative critics during times of cancel culture (see “El crítico matón”).

In the Paris Review, he affirms that the Latin Americans, Calvino, Kundera, and postmodern North American literature (Cercas taught in Illinois) saved him from “the baroque and pompous” Spanish literature of his time, and it is no accident that his recent novel (on Pope Francis), El loco de Dios en el fin del mundo (2025), is advertised as a “novel without fiction.” The eighth section, “La literatura es dinamita,” No callar’s longest, provides very opulent and fruitful views on world literature, recalling the nonfiction of Doris Lessing, Amis, Julian Barnes, Salman Rushdie, and Lydia Davis, as expressed in letters to Belgian writer Hedwige Jeanmart about crises of faith in literature, new readings of Cioran, García Márquez, Cervantes, César Aira, the pettiness of literary types, sloganeering, Europe and the novel, Houellebecq, the Nobel Prize, and the like.

Section 8’s last three autobiographical essays dovetail into the ninth and final section. “Autobiografía literaria en cuatro actos” is a revealing set of prologues to new editions of four of his earlier narratives, while “Soldados de Salamina, muchos años después,” which begins with a discussion of T. S. Eliot, is a frank assessment of Soldiers of Salamis, the novel that brought Cercas worldwide fame. “Coda: ¿Quieres hacer el favor de callarte, por favor?” dovetails into “No callar,” the first article in the final section, “Cuanto sé de mí.” Both pieces offer Cercas’s self-explanation of the culture and activism in which he sees himself immersed inevitably, knowing when to shut up.

No matter what he assails or praises, literature, particularly novels, is what keeps him sane, as he also pinpoints in his apology for the siesta, on using dictionaries, or “a double NGO called family and friends,” or letters between Coetzee and Auster (with Philip Roth in the fray). In that context the two final sections are very different from No callar’s first half, centered on drastic stances of the left and the right. The last section, “Cuanto sé de mí,” is an honest self-analysis composed of twenty-two brief articles and the speech “Política y ciudadanía,” given in the province in which he was born. Asserting that “there are many reasons that explain why writers, or at least novelists, are or should be the opposite of politicians,” he concludes that politics is too important to leave it in politicians’ hands.

Throughout Between Parentheses, Bolaño praises Cercas, extoling his constant flirtation with hybridization, “true” or historical fiction, and hyperobjective fiction, “though whenever he feels so inclined he has no qualms about betraying these generic categories to slip toward poetry, toward the epic without the slightest blush.” In the new prologue to Relatos reales (2020), Cercas praises mestizo literature, affirming that articles are not poems or essays, just tales, real tales. And so it is with No callar’s relentless combination of common sense and argumentative brilliance, outperforming his eminent contemporaries in dealing with perfect storms of cultural changes.

Will H. Corral

San Francisco