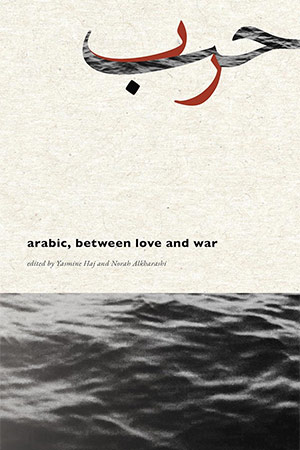

arabic, between love and war

Toronto. Trace Press. 2025. 146 pages.

Perhaps the seminal diasporic experience is visiting home after quite some time away and having to fake a laugh to hide that you do not understand what a beloved cousin is saying. Or perhaps you think you understand, but the response carefully lined up in your head is met only with a puzzled look, a pause trailed by a fake laugh of their own. Some awkward but earnest fumbling about leads you both nowhere. Whatever subject you were on is dropped. Although beloved cousin is right there on the other side of the kitchen table, they appear as if a speck in the distance. As if you thought a single plane ride could possibly traverse the gulf opened up by years spent in contrary drift.

The Arabic word for diaspora is shatāt: literally, to be dispersed or scattered, dissolved, pulled apart; to be diasporic or in diaspora is to be “in dissolution.” Born in such a condition, arabic, between love and war is a bilingual anthology of Arab poetry that reckons with and against this birthright. It is a forum invested in reestablishing rapport, a site of nucleation where the solute crystallizes out of the solvent. In the words of editor Yasmine Haj, the anthology “speaks to itself” through the poetry of its contributors and the ambassadorship of its translators.

Diaspora permeates the anthology’s being. Originally conceived and compiled over a series of translation workshops spanning 2022 to 2023, the collection comes as a patchwork of authors and translators distributed throughout time and space. Modern and contemporary Palestinian, Lebanese, Tunisian, Egyptian, Iraqi, and Syrian poets, from National Book Award winner Lena Khalaf Tuffaha to largely unrecognized Da’ad Haddad, all appear in and through an equally multiplicitous cast of translators.

This is not to say that translation plays its usual role of domesticating the indigenous Arab voice and prettying it up in accordance with the tastes of the Western literary landscape. Indeed, in recognition of the fact that the act of translation is “as much a summons to perform in front of others who have othered us, as it is an invitation to impart knowledge,” translation here flows in both directions. Every poem in the collection, whether originally Arabic or English, comes with its corresponding twin. The effect of this on the page is striking: visually, the translation and its source stand face to face on even ground. And as the usual coordinates mapping margin/center, source/translation, and primary/secondary lose their orientation, the collection’s translators make use of the newfound space to indulge playfully in rendering double entendres, puns, and hidden allusions, adding an additional layer of meaning in the process. The anthology simultaneously invites bilingual readers to join in on the dialogue in motion between original and translation, while ensuring that both arabo- and anglophone audiences share a common corpus.

The poetry itself is organized along the themes of love (ḥubb), war (ḥarb), and “interval” (tanhīdah)—the interstitial space between ḥubb and ḥarb. These themes are well chosen, functioning as flexible bases for a common poetic lingua franca: love and war at once invoke the poetic traditions of classical Arabic, while remaining oriented toward the violence of the present day and the various intertwined trajectories of modern Arab history. These themes bleed into, resonate with, and oppose one another, allowing for a multiplicity of formal, stylistic, and political assertions to coexist. As Qasim Saudi’s “I measure the distance from Baghdad to Africa’s shore / as a long spear rests on my back / with ten swift rifles” concludes the theme of love, Lamia Abbas Amara introduces the topic of war with a love letter “To a Fighter on the Frontlines”: “Tomorrow, I will embrace the valour in you / and forgive the cold of autumn nights / and their loneliness” just as Da’ad Haddad laments in ecstasy: “I am she / who brings flowers to her grave / and weeps from the pull of poetry.”

Entering the ranks of recently published anthologies of Arab poetry like Heaven Looks Like Us (Haymarket Press, 2025), We Call to the Eye and the Night (Persea Books, 2023), and This Arab Is Queer (Saqi, 2022), arabic, between love and war resists the dissolutionary action of exile, ethnic cleansing, and forced displacement. The anthology serves as a rendezvous point, occasioning a rare chance to gather in the midst of a context of historical forces conditioned and catalyzed by colonial violence to make strangers of entire nations in the Arab world. It is a chance to trade urgent memos, pass along communiqués, and pour out our souls to each other before swiftly taking leave, once more, into the fray.

Nour Eldin H.

Minneapolis, Minnesota