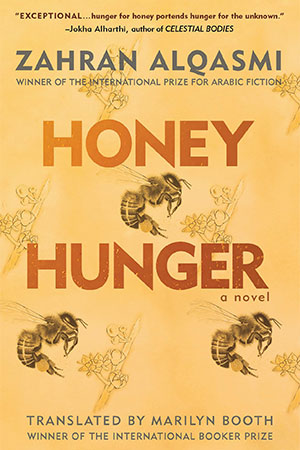

Honey Hunger by Zahran Alqasmi

Cairo. Hoopoe. 2025. 292 pages.

For the reader who knows little about Oman, Zahran Alqasmi’s third novel, aptly titled Honey Hunger—an unusual tale about hunters of wild honey in the mountains—has a sweet novelty. Versatile in many literary genres, Alqasmi has published four novels, ten poetry collections, and a collection of short stories. Recognized internationally, he was awarded the International Prize for Arabic Fiction for his novel The Water Diviner in 2023. Honey Hunger does not blow any trumpets on political issues but instead follows another melody by examining a small, unknown band of colorful characters who thrive in a magnificent natural landscape, full of risk.

In the opening chapter, we are introduced to Azzan, a withdrawn beekeeper, who has great sympathy and understanding for his bees, many of whom he lost because of the severe winter. A friend persuades him to move his bees from the White Mountains to Juba, two hundred and fifty kilometers south. His solitude is broken by the mysterious appearance of the shepherdess Thamna, whose plaintive tawwibehs, poem-songs, he hears.

Although the novel begins with Azzan’s point of view, the omniscient narrator probes the minds of other characters and hearsay to give us a complex picture of village life in Oman. When Azzan moves to Juba with his bees, he is befriended by a Bedouin, Hamud, and his wife, Salama. Despite his modest Bedouin lifestyle, Hamud has thousands of rials in the bank from training camels for races for wealthy Gulf emirs. Azzan’s new home at first seems idyllic, but then he is confronted by others in the area, who are annoyed by his bees. Hamud, who is well connected, intercedes for him when he is told he must have a government permit to raise bees.

Azzan’s obsession with bees is not just confined to raising them, however, but also with hunting them in the mountains. Part of the thrill of hunting for wild honey is the adventure, a little like miners panning for the illusory gold. Abdallah, one of his comrades, reflects: “The exultation of the search itself—not out of need but for the joy of the adventure, looking for a wild and elusive beehive when everyone else who had been searching for it had come back utterly worn out and empty-handed.”

The reserved Azzan finds two kindred spirits. Abdallah is a feisty, voluble storyteller from a family of mountain climbers, nicknamed “the honey fly.” He understands the secretive nature of bees—the key to finding the hives is locating their water supplies. The other comrade is Al-Hatati, an older man who is not afraid to scramble up mountains or call it straight. He is the one who found Azzan and broke the news to him that both of his parents had died—and helped him with their funeral rites and also introduced him to a new addiction, hunting for wild honey.

Alqasmi uses the metaphor of honey to refer to other types of sweetness that ensnare his characters. Locals who work for British Petroleum bring foreign alcohol to the village. Many of the young men are drawn to the drinking sessions by the sweetness of the oud, the music of the lute. Once the foreign booze dries up, many of the men start drinking cologne while others succumb to vices of their own: the eloquent Abdallah cannot resist women, while Al-Hatati cannot do without tobacco.

Alqasmi also gives readers an insight into the strictly segregated, enclosed world of village women in Oman, ruled by ignorance, superstition, and gossip. Only one woman knows how to read, Wadha, and she reads medieval tales, stories from the Qur’an, and mystical and love poetry to the other women. Sarah, one of her listeners who has fallen secretly in love with Azzan, takes the idealized romantic poetry too much to heart. Sadly, her restricted life and infatuation fuel her depression, and she eventually wastes away without proper medical attention. The omniscient narrator describes examples of depression, sleepwalking, and epilepsy in the community that go untreated; instead, these maladies and illnesses are explained away by malicious rumor and superstition. When Wadha withdraws from the other women, she is called a witch.

Alqasmi’s poetic descriptions of the mountains and the desert of Oman have been rendered sensitively through Marilyn Booth’s precise translation. Azzan himself identifies with the natural world so profoundly that he feels like he is a bird when he discovers his love for Thamna: “His spirit began to beat its wings, trying to rise out of its cage to soar into the lands behind those mountain peaks and the dips and gorges that separated them.” Azzan marvels at how different the landscape is in Juba: “The sand plied its curves like the sea, waves birthing new waves into the distance, on and on. He began scrambling up a higher hill, his feet plunging deeper into the sand as it became softer.”

Out on an expedition by himself, caught in a storm, he falls in a cave. Abdallah and Al-Hatati search for him; however, he is rescued by Thamna, who pulls him out with her donkey. He is so badly hurt that she takes him to the hospital but quickly vanishes. As one might expect from such an original writer, Alqasmi resists a predictable resolution for this memorable and evocative novel.

Gretchen McCullough

Cairo