Spaceman in Translation: Adapting Identity from Page to Screen

Comparing the novel Spaceman of Bohemia to its film adaptation, Spaceman, the author relates the arcs of Czech history and Adam Sandler’s career, finding that both represent a blend of dramatic tragedy and absurdist comedy.

When you think ‘Czech astronaut,’ Adam Sandler isn’t always the first person that comes to mind,” says author Jaroslav Kalfar. Sandler plays the lead role in Spaceman, the 2024 film adaptation of Kalfar’s 2017 novel Spaceman of Bohemia. His astronaut character, Jakub Procházka, embarks on a solo voyage to a mysterious purple dust cloud. As he drifts through the emptiness of deep space, Procházka reckons with both the sudden, unexplained abandonment of his wife on Earth and the appearance of a Paul Dano–voiced, Nutella-slurping arachnoid alien.

Procházka’s character—both comedic and dramatic—fits in with Sandler’s filmography. When you think “Adam Sandler,” the first thing that comes to mind could be “Happy Gilmore boxing Bob Barker.” Or it could be “Howard Ratner risking everything on a big parlay.” Despite critical malignment during his 1990s Saturday Night Live and goofball comedy era, films like Uncut Gems and passion projects like Hustle—plus a nostalgic fondness for earlier output—have reversed the critical consensus. Adam Sandler has range. He takes risks. When you think “astronaut in a $40 million moody, contemplative film,” Sandler is a reasonable choice.

Procházka’s Czechness—an integral aspect of the source material’s characterization—complicates Sandler’s casting. Through references to Czech history and mythology, Spaceman of Bohemia places Procházka’s Czech identity at the forefront. In long chapters about the character’s childhood—which the film glosses over in brief flashbacks—Kalfar explores how Bohemia’s changing political and economic systems have impacted multiple generations.

American screenwriter Colby Day and Swedish director Johan Renck focus less on Czech mythology and more on Procházka’s relationships with his wife, Lenka, and the arachnoid alien, Hanuš. Procházka retains his Czechness, but the filmmakers hint at it in minor background detail. His spacesuit has a patch of the Czech flag, but another symbol could be sewn in its place without any significant alteration. In Spaceman of Bohemia, as the elongated title suggests, Jakub Procházka must be Czech. In Spaceman, he can be Adam Sandler.

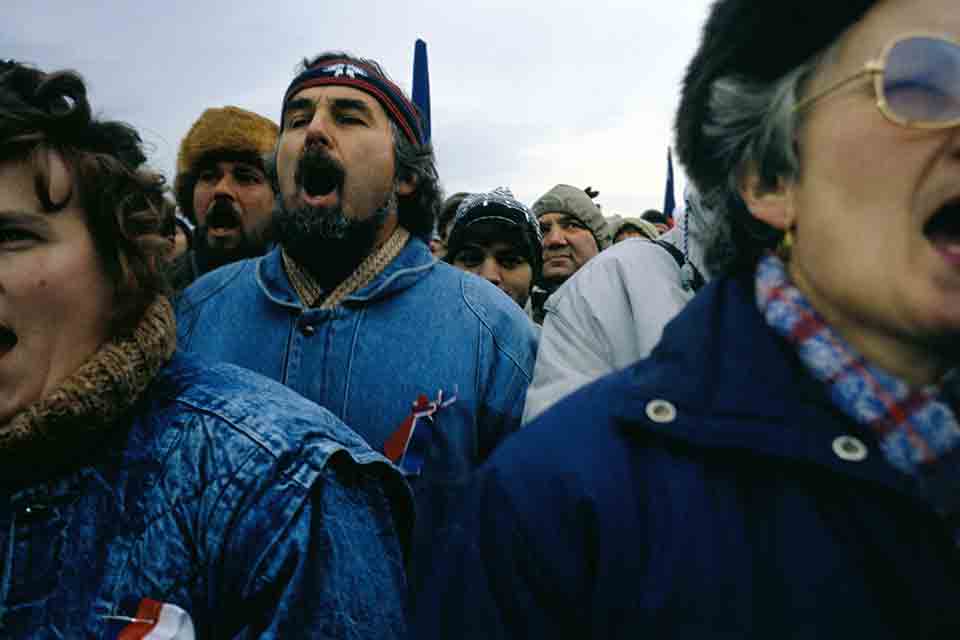

“Czech astronaut” and “Adam Sandler” appear incongruous, but both Sandler’s career and Kalfar’s portrayal of Czech history can be described in the same way as Procházka: a blend of absurdist comedy and tragic drama. The past three generations of individuals living in Czechia, where Kalfar’s novel is set, have experienced multiple governmental transformations. Procházka’s grandparents were born in Czechoslovakia, a nation established in 1918 after the collapse of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. They lived through World War II and the Nazi occupation of 1938–1945. With Soviet support, the Communist Party took over in 1948: the period in which Procházka’s parents came of age. After a brief era of reform socialism in the 1960s under Alexander Dubček, Soviet tanks entered Prague to crush dissent and reverse Dubček’s liberal policies, backing his more Moscow-aligned successor, Gustáv Husák. Procházka’s generation was born under this return to hardline communism but came of age after the 1989 Velvet Revolution’s peaceful transition to capitalist democracy.

Both Sandler’s career and Kalfar’s portrayal of Czech history can be described in the same way as Procházka: a blend of absurdist comedy and tragic drama.

Through Czechia’s decades of power transfers at the whims of larger world powers, an underlying Czechness has persisted. Much of Czech art and culture contains an undercurrent of dry, sarcastic, satirical humor. Kafka, Kundera, Hašek, and Hrabal are the most internationally renowned literary examples of such humor, each from different eras. Kalfar recommends Jiří Hájíček, Petra Soukupová, and Magdalena Platzová as contemporary must-reads.

This element of Czech identity exists in part due to political repression and upheaval but also transcends it. Although international audiences know the dissident music and poetry associated with writers like Václav Havel, who adored Lou Reed and served as the Czech Republic’s president from 1993 to 2003, many Czech writers are products of their environment rather than active antagonists against it. As government systems have deemed various forms of art to be subversive, an absurdist comedic sensibility has persisted.

Spaceman of Bohemia finds a Czech author using absurdism to examine politics’ impact on individuals. This includes the ongoing embrace of Western capitalist democracy. A handful of ridiculous corporations sponsor Procházka’s mission, satirizing modern commercialization. The government praises the astronaut as a national folk hero, commodifying him through merch sales. Raised during the end of the Eastern Bloc era, with a personality shaped by those times, Procházka represents a generation pushing forward into the excesses of capitalism regardless of the consequences. It takes an absurdist element—the alien spider Hanuš—for Procházka to confront his true place in a universe governed by natural laws far beyond human comprehension.

In one of the novel’s flashbacks set on Earth, in Prague, Procházka travels to the busy central area of Wenceslas Square. The narrator describes his surroundings: “Alcohol sales keep the vendors in competition with the McDonald’s, the KFC, the Subway, those invaders seducing the populace with the sweet breath of air-conditioning, restrooms free of toilet paper charge, hot food injected with chemical pleasure.” The capitalist period of Czech history is marked by this corporate American occupation. Profiting off an astronaut on a pointless mission to unexplored territory pushes capitalist thinking to a plausible extreme.

On the topic of KFC, Kalfar tells me, “We Czechs have embraced capitalism with open arms, and our transformation brought much prosperity, so it is a complicated issue, because this process of corporations coming in and changing the country of course looked great as it was happening, after decades of oppression and austerity, but where are we headed now? Our politicians are adopting the American model of society: cutting retirement payments for seniors, allowing college to become expensive, disassembling our very affordable healthcare system. Many things trouble me about capitalism, and this is one of them: the idea of running a country like a corporation. So, now we have overembraced capitalism. Instead of looking at it merely as an economic system, we are making it a philosophy of living, the main organizing principle for Everything. We should’ve stuck to just enjoying our Original Recipe.”

Other characters in the book help illustrate earlier Czech periods. Procházka’s father represents both the idealistic hope of socialist revolution and the ensuing hypocrisy of the Soviet era: he was a party spy who secretly listened to confiscated Elvis records. Procházka’s grandparents have lived through it all, including the Nazis, and they do their best to survive while providing for their descendants. A character named Shoe Man haunts the Procházka family in a vengeful pursuit: Procházka’s late father arrested and tortured him under communism, and under capitalism Shoe Man schemes to drive Jakub and his grandparents off of their rural land with intergenerational spite and malice. The interactions between these characters—all of which, sans the vague references to Procházka’s father, are excised from the film script—call forth the way individuals behave according to (or regardless of) the political situations in which they find themselves.

As a response to Shoe Man’s harassment, Procházka attempts to atone for his father’s transgressions but inadvertently mimics the same path. Procházka risks his life for the glory of the Czech Republic, willfully endorsing disinfectant brands and cinema chains as he journeys into the unknown. He’s happy to be a cog in the machine, because it brings him a false sense of power and importance. Procházka submits himself to his nation’s new system, like his father did the previous one. The systems they exist in are theoretical opposites, but the full-forced manner in which the characters embrace them is the same.

When Shoe Man confronts Procházka at a pivotal moment, he says, “If the Americans had liberated us from Hitler before the Russians, we could’ve been free. Your father and I might’ve been great friends.” If Procházka’s father grew up in a capitalist system, Shoe Man suggests, he would have behaved differently. Kalfar claims the opposite could also be true. A man who becomes a party spy might become a profiteering CEO under capitalism.

“Power is what drives people to do truly brutal things, and this is the case in any political system,” Kalfar says. “Jakub’s father would make for a terrific capitalist, because he has no trouble being a true believer in order to position himself closer to power.”

Procházka deviates from his father’s absoluteness in that he does—amidst an existential crisis on the doomed space shuttle—question how his behavior aligns with his intrinsic values. Operating a rocket ship makes him a legend but costs him his marriage and sanity. The price of his ambition is horrifying loneliness, and he breaks from generational trauma to pontificate on the worthiness of it all. Hanuš steers him toward epiphany.

Due to the inherent formal limitations and time constraints of film compared to prose, the adaptation of Spaceman of Bohemia loses the significance of these Czech-specific themes. The “Czech Space Program” becomes the “Euro Space Program.” A competing Russian spaceship becomes a South Korean ship, losing significant historical contextualization. Kalfar suggests that such changes might have been a result of the current geopolitical landscape, which emphasizes how today’s artistic decisions are made with capitalist considerations.

Film presents opportunities that don’t exist in literature, and Spaceman exploits them. As Sandler floats through Jan Huš 1—the space shuttle named after the Czech theologian who launched the reformist Hussite movement—the set continuously rotates behind him. It’s a disorienting effect that amplifies the unfamiliar motions of space travel. In the absence of Kalfar’s narration, these visual tricks call forth how the unsettling qualities of the ship heighten Procházka’s despair. The camerawork on Earth is also unsteady, mirroring Procházka’s uncertainty about his wife’s whereabouts or fuzzy memories of his father. Seeing and hearing Hanuš, too, establishes a quiet and somber tone that novel readers might interpret differently.

Any adaptation is a form of translation, but Spaceman of Bohemia has already been translated at multiple levels.

Any adaptation is a form of translation, but Spaceman of Bohemia has already been translated at multiple levels. Kalfar grew up in the Czech Republic and immigrated to the United States at age fifteen. He wrote the book in English about Czech characters in Bohemia. His characters translate ideas and cultural values across generations. Procházka’s relationship with his parents and grandparents reflects the current state of Czechia, in which an older generation grew up under communism and the younger generation grew up under KFC. Because of the unavoidable psychological toll political systems have on individuals, family members can be fundamentally at odds with one another. “All of them are haunted by the different political movements and historical tragedies that shape their time,” Kalfar says. “Often, they misunderstand each other, and the tension of the misunderstanding is at the heart of the shame that drives Jakub to accept a suicide mission.” The impossible process of translation, therefore, is the novel’s driving force.

Kalfar says that he intended to explore another type of translation: reframing Czech identity. “For decades my nation was associated with communism, dissidents, fighting for freedom of art and expression,” he says. “We won that struggle—so, what now? Who are we? Where are we headed? And what do we want to be known for?”

These are all questions Adam Sandler might be asking himself as his career undergoes another transformation. Decades removed from Opera Man, Adam Sandler is taking on supporting roles in films like You Are So Not Invited to My Bat Mitzvah, starring his wife and daughters. He’s also taking chances on intimate Netflix dramas adapted from contemporary literary speculative fiction. Sandler could provide a template for Czech artists like Kalfar. If his career parallels Czech history, there is hope of reclaiming the narrative. Recognition is long overdue.

“I used to think of Adam as the distinctly American funny guy, and nothing else,” Kalfar says. “But now I’ve experienced the depth of his devotion to his roles, his curiosity, his love for his family, his seriousness, his warmth. Similarly, I always hope my work might inspire people to look deeper into my country. Beyond the dissident art that came out of communism, beyond Kafka and Havel, beyond the things a lot of people associate us with most today, which are beer and pornography.”

Of all the Czech specificity lost in translation from the book to the film, one crucial mythologization remains: Procházka naming the alien spider Hanuš. The name refers to a well-known Czech legend. The story goes that Hanuš built the astronomical clock in Prague’s Old Town Square in 1490. The local government was so displeased that they blinded him so he could never build another clock. So he sneakily disabled it, and no one was able to fix it for a century. Now, it’s one of the city’s top tourist destinations and a spectacle of primitive genius. Historians claim to have debunked the story of Hanuš, but the significance of the legend being passed down for generations makes it, in a sense, real.

“So much of Jakub’s motivation is driven by conflict about nationalism and his father’s relationship with nationalism,” Kalfar says. “Czech myths and legends are crucial in this, as this kind of lore is tied up intimately with national consciousness. The legend of Hanuš was a powerful one for me when I was growing up, and it made sense that it would be powerful for Jakub too, because it is a tale passed on from his ancestors. A myth so powerful that it is the first thing that comes to mind when he names his life’s greatest discovery.”

What’s the first thing that comes to mind when you think of Adam Sandler? In addition to the aforementioned roles, a wide-ranging multitude of characters might appear—including, now, “Czech astronaut.” It just so happens that the Czechness of that astronaut, so crucial in the novel, has been relegated to the background, like so much of both Adam Sandler and Czech artists’ cultural contributions. That’s both tragic and absurd, but at least it can be dealt with through comedy.

Burbank, California