The Monkey King’s Diasporic Reassemblage in Sinners

While the Monkey King’s on-screen presence in Sinners is barely longer than a minute—a fleeting interlude within a dense, two-plus-hour southern gothic tapestry—it still resonates. In her review, Tammy Lai-Ming Ho looks at the history of this monkey deity that makes an appearance in Ryan Coogler’s latest film.

What happens when a stone-born monkey deity from a sixteenth-century Chinese cosmological epic is summoned amid the rumble of a 1932 Mississippi juke joint—an informal venue of music, dancing, drinking, and gambling, largely run by African Americans in the southeastern United States? Sinners (2025), Ryan Coogler’s audacious southern gothic horror-musical, is one of the year’s most electric and expansive originals. The film tells the story of twin brothers Smoke and Stack (both played by Michael B. Jordan) returning from World War I–era Chicago to open a juke joint and confront vampiric forces intent on feeding on Black creativity.

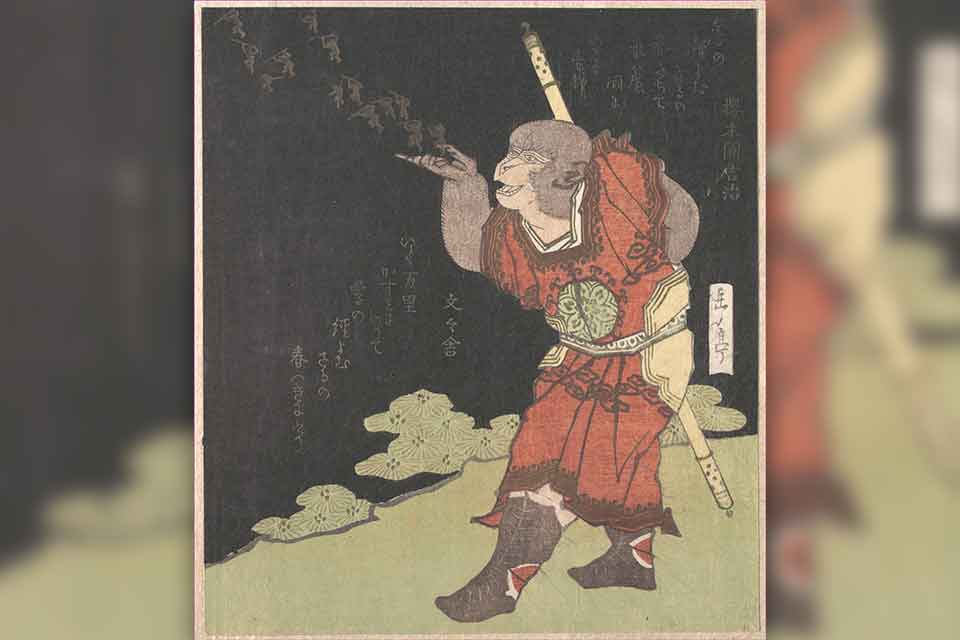

The appearance of Sun Wukong, or the Monkey King, in this setting is no decorative digression. It marks, rather, a temporal and ontological rupture. Across a phantasmagorical continuum of sonic “epochs”—beginning with the voiceover narration, There are legends of people born with the gift of making music so true it can pierce the veil between life and death, conjuring spirits from the past and the future—the film moves from the polyrhythmic thrum of West African drumming to the field hollering and haunted cadences of Delta blues; into the fervent swell of gospel and the improvisational pulse of jazz; then catapults viewers into anachronistic rock and roll, with electric guitar riffs crackling through the smoke; and finally arrives at the analog textures of hip-hop breaks, complete with a DJ scratching at a turntable altar. Here, the juke joint morphs into a chamber of ancestral reverb, an archive of memory in motion. Into this cacophonous sanctuary, the Monkey King materializes—fully adorned in xiqu opera regalia, limbs flickering with stylized combat and mythic charge.

The Malaysian actor Yao, who plays Bo Chow in the film—the patriarch of the Chinese family living in the rural Mississippi town at the heart of the story—was invited by the creative team to suggest an iconic figure from the Asian imaginary. He selected Sun Wukong, a choice that attests to the enduring magnetism of the myth across both the sinophone and Southeast Asian worlds. The presence of Wukong is not symbolic nor externally imposed; it emerges from within the film’s diegetic logic. Characters such as Bo Chow; his wife, Grace Chow; and their daughter, Lisa, do not stand as detached witnesses to Black suffering but as participants in its ongoing drama and endurance.

Sun Wukong’s mythological roots trace past to Journey to the West, a sixteenth-century Chinese epic novel—widely attributed to Wu Cheng’en—where he is born from a magical stone atop the Mountain of Flowers and Fruit. Gifted with supernatural strength and intelligence, Wukong learns martial arts and Daoist practices, gaining immortality. After wreaking havoc in Heaven and defying the celestial order, he is imprisoned by the Buddha beneath a mountain for five hundred years. His eventual release is conditional: he must accompany the monk Xuanzang on a pilgrimage to retrieve sacred Buddhist texts from India. Along the way, Sun Wukong transforms from a rebellious, chaos-sowing figure into a disciplined guard, using his magical staff, cloud-somersault ability, and shapeshifting powers to overcome demons and protect the monk. He is a rogue-turned-redeemer in this legendary arc.

In Sinners, the role of the Chows extends beyond token inclusion: they are local grocers who provision the juke joint, trusted figures in a town fractured by segregation. In the film, their operating of two different shops—one catering to Black patrons, the other to white—positions them as cross-community interlocutors, enacting a grounded, pragmatic solidarity. This very embeddedness conditions the plausibility of the Monkey King’s emergence. His appearance is not a fantastical imposition but a crystallization of the entangled realities between Chinese and Black lifeworlds in a South that is both violently segregated and intimately cohabited. Thus, the Monkey King enters, not as an alien element, but as a consequence of this entanglement. His arrival becomes an event engendered by the very structure of the world depicted. In that moment, Chinese opera and mythic figuration do not interrupt the film’s temporal weave but are enfolded within it, justified—indeed, compelled—by the Chows’s presence. Rather than a figure of multicultural décor, Sun Wukong inhabits a Black performative current, articulating a common trickster identity rather than rehearsing difference as spectacle. It is no coincidence that Sinners has emerged as one of 2025’s best-performing original releases—grossing over US$363 million globally—a commercial success that affirms the cultural urgency and resonance behind this daring once-upon-a-juke-joint convergence.

The Monkey King’s appearance is a crystallization of the entangled realities between Chinese and Black lifeworlds in a South that is both violently segregated and intimately cohabited.

In the compressed space of Sinners, myth migrates—and, in migrating, transmutes. Sun Wukong, long sedimented within Chinese cosmology and narrative, finds himself not so much dislocated as re-assembled. No longer solely a celestial rebel, he becomes a diasporic node, articulating not origins but trajectories, seeking operational resonance instead of legibility. The film does not explicate him but situates him—within a distributed network of ritual gestures, diasporic displacements, and sonic insurgency. For those who recognize the character, he vibrates with a certain infrasensory charge; for others, he remains a figure suspended in ontological latency. This is not failure of recognition; it is an epistemological stance: myth here does not require explanation—it requires circulation.

As the carnivalesque story of the Monkey King journeyed West—first via literary translation, then through graphic novel, cartoon, and cinematic adaptation—he underwent a process of modular transformation. From Maxine Hong Kingston’s Tripmaster Monkey (1989) to Gene Luen Yang’s graphic novel American Born Chinese (2006; see WLT, January 2024), he became an artifact in Asian American cultural critique, mobilized to contest racialized typologies and diasporic longing. When he passes into the Black diasporic aesthetic, a distinct type of engagement emerges, in jazz, hip-hop, or revolutionary dramaturgy. Here, Sun Wukong is less a figure of cultural heritage than a flexible agent, adapted to various expressive ends.

Fred Ho’s decade-long project Journey Beyond the West: The New Adventures of Monkey premiered in full in 1997, following a 1995 concert version. In this genre-defying hybrid of jazz opera, ballet, and martial arts spectacle, Sun Wukong, drawing inspiration from both the Chinese Monkey King and the African American “signifying monkey,” becomes a revolutionary trickster: he renounces immortality and galvanizes the oppressed. Central to the work is Afro-Asian sonic fusion: the music fuses dissonant improvisational jazz—a form Ho viewed as a site of radical resistance—with Chinese traditional instruments and live martial arts choreography. Ho’s grounding in the Black Arts Movement and Asian American activism informs this blend, treating jazz as resistance embodied. Crucially, Blackness here doesn’t meld into the narrative—it intervenes tactically, bringing African American resistance into dialogue with Chinese diasporic critique. In scenes like the vividly titled “The Allies Arrive: The Gathering of the Tricksters, Guerrillas, Womyn Warriors, Outcasts and the Oppressed,” Black and Chinese elements intersect strategically—not unified but aligned in defiance. The work was performed by ensembles Ho led, including the Afro Asian Music Ensemble and the Monkey Orchestra, both dedicated to revolutionary performance. In his program notes, Ho remarks that “the work is a synthesis of Chinese folk music and opera, with African American music, radical political allegory, and American popular culture.”

This mutual refusal echoes in the semiotic assemblage elaborated by Henry Louis Gates Jr., whose The Signifying Monkey (1988) delineates the trickster as a foundational trope in Black rhetorical tradition. Rooted in African American folklore, Gates’s monkey is a liminal operator, a double-speaking, genre-scrambling agent—cognate, one might say, with Sun Wukong. Both operate within traditions of orality and embodied performance, wielding ambiguity as tactical delay, refusal as survival. Their resemblance is not genealogical but topological, their functions rhizomatic rather than hierarchical.

The racialized term “monkey”—employed historically to derogate both Black and Asian bodies—becomes, in this context, a semantic residue ripe for inversion. Through the deliberate appropriation of the Monkey King, diasporic creators reconfigure insult as reclamation. The slur is not simply negated—it is retrofitted as a symbolic armature. Sun Wukong does not merely survive the West; he colonizes its representational machinery.

* * *

The Monkey King’s brief apparition insists that the story of Chinese Americans in the Delta matters.

While Sun Wukong’s on-screen presence in Sinners is barely longer than a minute—a fleeting interlude within a dense, two-hour-plus southern gothic tapestry—it still resonates. As a dreamlike cameo in the juke joint’s musical fever, the Monkey King doesn’t steer the narrative, he punctuates it. His dance- and opera-inspired attire serve as a gentle nod: an echo of Asian diasporic memory subtly woven into the broader fabric of 1932 Mississippi.

Rather than a messianic figure, Sun Wukong functions as an ephemeral spark—a subtle gesture toward diasporic entanglement. He reminds us that Chinese grocers like the Chows mediated in Black spaces under Jim Crow, suggesting shared margins without overshadowing the central Black narrative. His brief apparition insists that the story of Chinese Americans in the Delta matters, yet he never diverts attention from the heart of Sinners: the blues, vampires, and a community bound by resistance. Ultimately, the Monkey King’s cameo is best understood as a whisper across the blues-infused night that signals inclusion without demanding redemptive weight.

Richard Charles Lee Canada–Hong Kong Library

University of Toronto