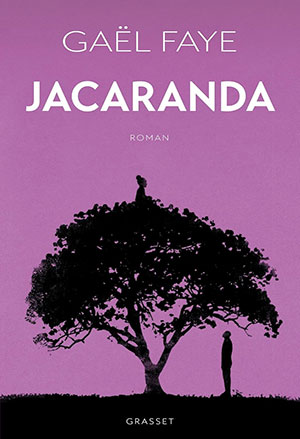

Jacaranda by Gaël Faye

Paris. Grasset & Fasquelle. 2024. 282 pages.

Paris. Grasset & Fasquelle. 2024. 282 pages.

Winner of the Prix Renaudot 2024, Jacaranda may be the novel that is intimated in the epilogue to Petit Pays (2016; see WLT, July 2018, 78), Gaël Faye’s critically acclaimed debut novel. Twenty years after having been repatriated to France, Gaby, its Franco-Rwandan protagonist, returns to Bujumbura and recognizes the voice of his long-lost Rwandan mother in his old childhood cabaret. Muttering about the stains on the floor that she cannot remove, she suffers from survivor’s guilt after finding in July 1994 the decomposing bodies of her aunt Eusébie’s four children, massacred in their Kigali home in the early days of the 1994 genocide of the Tutsi.

Whereas Petit Pays narrativizes Gaby’s idyllic childhood in Bujumbura until the discordant tensions in the region leading up to Burundi’s civil war and the genocide in Rwanda shatter his haven, the multibranched vérité-fiction Jacaranda opens with Stella’s psychological breakdown when her mother, Eusébie, has the eponymous jacaranda tree on her plot in Kigali cut down to build a rental unit to pay for her daughter’s university education in the United States. Born in 1998, the twenty-one-year-old daughter is inhabited by her brother and three sisters, buried at the foot of the jacaranda in 1994 by Gaby’s mother, but whose presence she has always sensed sitting high up among the tree’s branches, out of her mother’s sight.

Jacaranda traces, in thirty multivocal chapters, Milan’s thirty-six-year journey to understanding what lies behind the tenacious refusal of his mother, Venancia, to open up about her Rwandan family. Explicitly stated years—1994, 1998, 2005, 2010, 2015, 2020—signpost his stays and travels between Kigali and Versailles where, as a twelve-year-old in 1994, horrified and uncomprehending, he watches with her and his French father the massacres unfolding on the French news and briefly that summer shares his bedroom with Claude, who arrives with a deep head wound and is presented as Venancia’s nephew. They meet again in 1998 during Milan’s first trip to Rwanda with his mother when the two sixteen-year-olds grapple with the Franco-Rwandan’s foreignness as a muzungu (a white European) before forging over three decades the trust that will bridge the genocide’s chasm for them.

Familiar characters from Gaby’s childhood cross over into Milan’s own first-person narrative. Mamie, Milan’s maternal grandmother, is back in Rwanda after years in exile in Burundi; and Rosalie, Stella’s great-grandmother, has rejoined her granddaughter Eusébie, whose very existence as a Tutsi survivor incarnates the dead and ensures that her people live on in the generations that follow hers. Gradually, Milan assembles Rwanda’s history from their stories, harking back over five generations to the royal court in Nyanza, before the divisive Belgian colonial rule tore the sovereign nation’s social fabric apart and created the calamitous retributive conditions in the ensuing postcolonial era that led up to the genocide.

Weaving testimonials that Milan witnesses at a gacaca court proceeding or during the annual commemoration events together with discussions to which he is privy as survivors confront their assailants and their own acrimony, Jacaranda’s architexture fills in the gaping memories with the buried truths that imperil trusted friendships, vindicate familial intimations, and appease consciences. The novel figures its own mise en abyme at the Kibuye wooden chalet on Lake Kivu: a library for the films, music, and books scavenged from the homes the génocidaires decimated and the recently acquired collection that Gaby inherited from Madame Economopoulos in Bujumbura. These create a space to hold and transmit to the new generations the testimonials and stories of their elders, whether written or even rapped—as in Faye’s 2022 album Mauve Jacaranda—to know the root of each life’s tree.

Sarah Davies Cordova

University of Wisconsin–Milwaukee