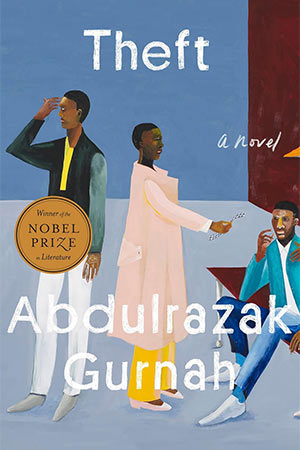

Theft by Abdulrazak Gurnah

New York. Riverhead Books. 2025. 256 pages.

Throughout his career, Abdulrazak Gurnah has constantly examined the historical and social transformations of East Africa, particularly the ways in which individuals coped with life before, during, and after colonial rule. His 1994 novel Paradise captured the region at a critical moment, as colonial powers began to exert control, while works such as Desertion (2005) and Afterlives (2020) delve into the impact of colonization. Novels like Memory of Departure (1987) and By the Sea (2001) explore the transition from colonial rule to independence, while his other works address the struggles of the postindependence era as well as topics of diaspora and exile. Across his body of work, Gurnah has traced the evolving identity-formation of East Africans from the late nineteenth century to the present. In his latest novel, Theft, published four years after receiving the Nobel Prize in Literature, Gurnah returns to Zanzibar in the aftermath of the independence movement, offering a complex portrait of individuals whose lives are shaped by the lingering effects of colonialism and the uncertainties of a nation on the brink of change.

Theft follows the intersecting lives of Karim, Fauzia, and Badar. Raya, Karim’s mother, who was forced into an unhappy marriage at a young age, leaves her son in the care of her parents while she remarries and relocates to Dar es Salaam. Karim, an intelligent student, earns a scholarship to study in the city, later securing a government job and marrying Fauzia, who was once an aspiring student, wanting to become a teacher. Badar, abandoned by his adoptive family, becomes a servant in Raya and Haji’s household when he is a teenager and serves them for years. Wrongly accused of theft, he eventually finds work at a hotel with Karim’s help. Karim and Fauzia’s marriage deteriorates when an English volunteer enters their lives. As the narrative draws to its conclusion, Fauzia and Badar get closer to each other, suggesting the possibility of a new future for them, while Karim departs for Europe for a traineeship.

The novel begins with explicit mentioning of the local sociopolitical situation in postindependence Zanzibar, referencing the “new security force that was formed as independence approached,” the members of which were learning how to run the country from British officers still present in the country. Moreover, several real-time incidents and events are referred to throughout the narrative to pinpoint the exact time in which the story unfolds, such as the Umma Party and the comrades being sent to Cuba for training and references to incidents including the Srebrenica massacre much later in the story.

The residues of colonial Zanzibar and their effects on the nation’s generational identity, however, manifest subtly throughout the narrative. Nearly all the older characters in the novel are either withdrawn or sulking, having learned to “bear life’s burden without grumbling.” This is evident early on when Raya’s father is introduced and the reader learns how “a bitterness entered her father’s mind after the revolution, and a recitation of injustices and grievances replaced the stories that had charmed her childhood.” This growing gloom is also reflected in Haji’s father, who “hardly ever spoke. His face was weary and down-drawn. . . . He seemed like a person grieving” and was “tense with discontent and maybe grief.” The older generation appears to either grieve the changes brought to Africa or, even more tragically, grieve for what the younger generations will endure in their struggle for freedom and independence.

Additionally, Fauzia’s mother is another significant figure from the pre-independence era whose worldview remains reflective of the past. Having lived through “several weeks of terror and violence from the uprising” in her youth, she is plagued by anxiety, constantly complaining about “footsteps on the stairs no one else heard, about voices in the street at night, which to her meant armed robbers, about shortages, about violence, about the brutality of the world.” Though no longer chained by colonial rule, these characters remain haunted and tormented by their shared histories.

The past is also reflected in the novel metaphorically: early in the novel, Raya explains to her young son, Karim, that she is suffocating at her parents’ house, saying how “everything smells stale and bad. It’s the dirt of years.” Their old building reeks of the past, and Raya, perhaps seen as an early link between the generations, wants to leave their troubled past behind, even her son, who is baggage left over from her unhappy marriage. There is also a moment later when Badar, Raya’s and Haji’s servant, visits his old village and realizes how “everything was difficult and everyone was poor and had to work hard,” something to which he was blind when he actually lived there himself.

As the narrative approaches the end of the twentieth century, global powers—particularly Britain and the United States—invest in and reshape African cities to fulfill their own “gilded fantasies of oriental luxury.” These countries exert their influence through new forms of exploitation. Badar, as an important witness of the changes brought to the hotel industry in Zanzibar, directly observes the lingering power dynamics in European and American tourists, sensing that “below the surface of those smiles lay a sense of self-assurance and self-absorption, an unacknowledged feeling of superiority. Who could blame them, when they saw the paltriness all around them?”

The troubling consequences of Africa’s exploitation are also reflected in the love affair that unfolds in the novel’s final section. Karim and Fauzia’s marriage collapses with the arrival of Geraldine, a British “volunteer” who presumably comes to help Africans but, in reality, disrupts their lives for her own pleasure—living out her own orientalist sexual fantasy at the expense of the locals. The novel’s title lends itself to multiple interpretations, one of which may be a reference to colonial powers acting as thieves, stripping Africa for financial gain—just as Geraldine does to Fauzia and Karim’s already fragile marriage.

Rich with cultural and religious references, the novel vividly highlights the Islamic atmosphere of Zanzibar and Tanzania, creating a complex tapestry of time and place while capturing the nuances of human interaction in mid- to late twentieth-century East Africa. There are frequent mentions of dhuhr and Juma prayers, reading the Holy Qur’an, celebrating Eids, and fasting during Ramadan. The cultural landscape of the time is also reflected in the novel’s language.

Much as in Paradise and other works by Gurnah, English is interwoven with Kiswahili and Arabic words and phrases, deepening the reader’s immersion in Zanzibar’s reality while simultaneously presenting local languages as tools of survival beyond the colonizer’s influence and gaze. In this way, a subtle form of linguistic resistance also seeps through the pages. Although many characters, including Fauzia and Badar, speak English, the persistence of Kiswahili and Arabic echoes through the tourist-laden regions of Zanzibar, asserting their presence despite foreign dominance. It is against this backdrop that the characters strive to find their identities and, to an extent, their futures.

Over the years, Abdulrazak Gurnah has explored the fate of colonial and postcolonial subjects whose lives are shaped by their public histories, and Theft is no exception. The novel’s protagonists remain tethered to their past, unable to escape the invisible constraints of history despite their efforts to move forward. While the novel’s ending hints at a hopeful future, readers cannot help but see these characters trapped in their misery—whether one calls it destiny or fate. Theft is not a radical departure from Gurnah’s previous works but rather a continuation of his tradition of depicting postcolonial struggles and resistance. He reminds us of the enduring hardships that colonized nations face, even long after independence. The Nobel Prize–winning novelist remains committed to what he has always done: giving a voice to the subaltern, to the voiceless.

Ramtin Ebrahimi is an early-career literary and film scholar whose work explores international cinema, postmodern literature, and metaphysical detective fiction. He has also translated books and stories into Persian.