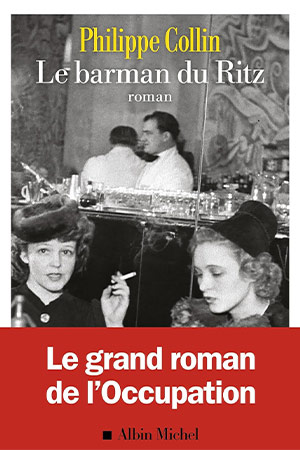

Le barman du Ritz by Philippe Collin

Paris. Albin Michel. 2024. 416 pages.

Philippe Collin is known for his biographical essays, including Léon Blum, une vie héroïque (2023), as well as for his work as a scriptwriter for bandes dessinées. Based on real events and characters, this fictionalized narrative about a famous bartender at the Ritz hotel in Paris during the German occupation of World War II is his first novel.

Frank Meier (1884–1947) was a working-class Austrian Jew who moved to the United States in his teens and painstakingly learned his craft in New York. He eventually moved to Paris and served in the French army during World War I. In 1921 he became the head bartender at the Ritz, where his innovative cocktails attracted both the upper crust of the Parisian nightlife and American expatriate authors (Hemingway, Fitzgerald). In 1936 the publication of his book, The Artistry of Mixing Drinks, cemented his international fame.

From 1940 to 1944, Meier had to conceal several things: not only was he Jewish, but so was his young assistant and the hotel director’s wife (with whom, in Collin’s retelling, he was secretly in love). In addition, as head bartender, the impeccably professional Meier was the repository of many secrets entrusted to him by various clients. In Collin’s narrative, he even served as an unwitting go-between, discreetly conveying messages that may have been linked to the 1944 German officers’ (unsuccessful) plot to assassinate Hitler.

As was the case for other luxury hotels in Paris, the Ritz, situated on the renowned Place Vendôme, was partly commandeered by the occupying German forces. In particular, the Luftwaffe used it for its Paris headquarters, with the hotel’s biggest suite reserved for Hermann Göring. At his bar, Meier thus saw his usual American clients quickly replaced by high-ranking German officers, including the already well-known writer Ernst Jünger.

These uniformed officers soon mingled, sometimes uneasily, with French celebrities who still came to sip on Meier’s cocktails, such as the playwright Sacha Guitry, the designer Coco Chanel, or the actress Arletty. Aside from the partial turnover of the clientele, relatively little seems to have changed at the Ritz’s exclusive bar, even as the strict rationing of food and coal meant that large numbers of Parisians were increasingly cold and hungry.

Collin adeptly brings out the strange atmosphere, at once surreal and threatening, in the apparently tranquil hotel and its bar, where a few Jews try to survive while German officers are regularly visible. Meier, the former Austrian Jew who had become a French patriot as well as a devoted member of the Ritz “family,” desperately attempts to maintain a façade of normalcy in the face of internal rivalries among the hotel staff, recurring shortages of the sometimes unusual supplies needed at a luxury hotel, the fear of searches and arrests by the Gestapo, and the constant threat of Allied bombing raids.

The novel alternates between third-person narration and first-person excerpts from Meier’s (fictionalized) journal. Each section is preceded by a date, which reminds readers about the dire situation in Paris from 1940 to 1944, even though the Ritz itself was partly insulated from the worst consequences of the German occupation. The narrative ends with the liberation of Paris, and Meier is happy to see Ernest Hemingway return to the bar that today bears his name.

An unexpected appendix provides pictures and brief accounts of what happened after the war to some of the real individuals, French or German, who are portrayed in Le barman du Ritz. Well researched and well written, Collin’s blending of fiction and historical facts is consistently fascinating.

Edward Ousselin

Western Washington University