My Heresies by Alina Stefanescu

Louisville, Kentucky. Sarabande Books. 2025. 118 pages.

If you are familiar with the work of German-language Romanian poet Paul Celan and find succulence in writers who weave surrealism into their writing, you may be intensely pleasured by Alina Stefanescu’s My Heresies. Here, she cores the apple with such punching lines as: “The theorist borrows a silhouette’s terror / to build his edifice” (“The First Gust of Special Relativity Is Weightlessness”). With verse not atypically American in its kaleidoscope of reference and history, writers like Stefanescu come from ancient nesting dolls, breathing the blue flame of poetry from worlds we learn of by reading:

The heart is the brick

of porch floor, the absent family, the dead

voices, gossiping between paper envelopes (“The Home Is Six Hens Who Never Lay Eggs”)

Stefanescu’s multilingual, panoramic diorama is evidenced by her expansion and understanding of tension, whetting lines of deeper meaning: immigration, transplantation, carried memories, undissolved pains, alongside histories. Which to keep? Which to discard? Who knows what’s true versus false? The poet, of course. “You said every lie is a nail in the eye of the dead.” Translated, in myriad patterns, starkly revealing. Such balance accomplished through observation and immersive pain. Stefanescu’s voice steadily holds the weight of generations and horror to light:

I am still terrible at division

I halved my whimpers when my mother vanished.

It is still easier to subtract than to be split. (“Cosmologies”)

In “Sonnet at the Ghost Commune,” Stefanescu evokes legacy (or heresy) via elegy to Paul Celan, whom most French-reading poetry buffs respect for his immediacy and urgency. In her poem “Other Horses,” shedding layers: “no respite in family hatred. Requiems / aside, those who romanticize being locked outside kinship / lack experience, or they lie.” And in the poem “We Keep Driving”: “This is the algebra of ashes— / the truest things stay impossible / to prove.” Stefanescu blends past/present, modern/ancient, her imagery and sophistication of recollection visceral: “When mom’s linden first entered the room; / all attendant bold ghouls in my blood.” This language aches to reflect decades of loss, longing, forgotten, and oddly enraptured beauty. As with Celan, making of grief an ingénue so bewitching, we are lost, all the way to the final poem, “Epiphaneia,” with ellipting lines like:

I have been

done by

bright offerings and trios of kings,

I have been offered free van rides

in return for a blow job

Not overt or grotesque for its own sake, but defecting and reflecting the jarring power of secrets, harnessing their contradictions, by repeating “offerings” and “offered” in parallel meanings, one grotesque, one ignoble. In the same poem:

We decimate

our selves

when aiming to see

the thing beyond

the thing

Leaving behind, poetry polaroids, then-and-now, danger/dissolution, Stefanescu’s last words in this collection look to brightness, seeking something “beyond the thing” of consumption, even of existence.

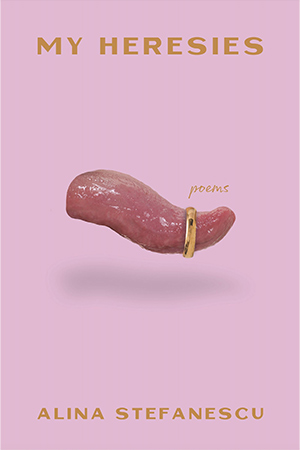

The author of several award-winning collections, Stefanescu’s success hasn’t diminished her purity as writer; she’s neither self-conscious nor solicitous of accolades. The startling cover should be mentioned: a glossy, wet tongue with gold ring circling its flicking tip. Stefanescu’s poetry is built on subtext, the abstract, oft-roiling presentation of poetry a fine bedfellow for a lurid pink cover. The message? “Each layer adds weight to ending” (“Parousia for My Children”). From Bucharest, Romania, to Birmingham, Alabama, an odd unfolding, and Stefanescu’s lack of pretention, with little explanation, softly implied through layers of meaning, performed naturally without fanfare. Such evidences, laid bare and permitted:

There is a life that broke

open before it could be chosen. There is more tenderness

than one can fathom in wearing what never happened.

(“Dream for Christina”)

Candice Louisa Daquin

Grasse, France