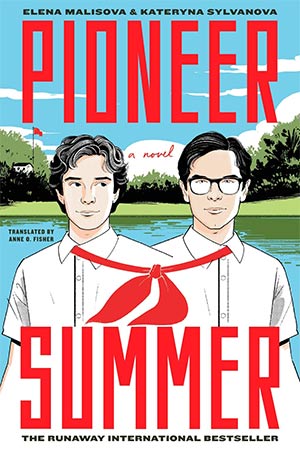

Pioneer Summer: A Novel by Elena Malisova & Kateryna Sylvanova

Trans. Anne O. Fisher. New York. Abrams. 2025. 448 pages.

Without doubt, Pioneer Summer is the most controversial and intriguing piece of Russian fiction to appear in recent years. Written initially as fanfiction in 2017, Elena Malisova and Kateryna Sylvanova’s novel tells the tale of Yura and Volodya, two young men who fall in love at a summer camp for Young Pioneers (the Soviet Union’s version of scouting) in 1986. The original fanfic amassed such a sizable and enthusiastic following that the independent publisher Popcorn Books picked it up in 2021. By mid-2022, Pioneer Summer had become a runaway best-seller, outstripping its competitors in the Russian book market. As copies of the book flew off shelves, a wave of TikTok videos, in which fans openly wept as they read about Yura and Volodya’s requited yet forbidden love, swept across the internet. At the same time, doyens of Russian culture denounced Pioneer Summer as “gay propaganda,” something notoriously outlawed in Russia, giving legislators the excuse they needed to revisit the initial 2013 ban. By the end of 2022, not only had a significantly broadened anti-LGBTQ+ law taken effect, but Pioneer Summer was likewise banned, while Malisova and Sylvanova were branded “foreign agents” and forced to flee the country.

The shocking fate of Pioneer Summer and its two authors begs the question of how popular romance, a genre often denigrated as escapism, could pack such a political punch in Putin’s Russia. To answer this question, we need only consider the backdrop that Malisova and Sylvanova chose for their story of gay love: late-Soviet Ukraine. By setting Pioneer Summer in a period that Putin’s regime has absorbed into its triumphant myth of Russian history and a location that his army has tried to occupy ever since it unlawfully seized Crimea in 2014, the book’s authors dared to tread on sacred ground. Moreover, they depict the largest impediment to the nascent love of Yura for his camp counselor Volodya as the Soviet era’s virulent homophobia, in effect critiquing the very anti-LGBTQ+ sentiment that Putin’s homophobic legislation foments. In other words, Malisova and Sylvanova’s romance reverses the valence of key Putin-era shibboleths, among them, nostalgia for the Soviet era, political homophobia, and Ukraine’s supposed nonexistence as a sovereign state.

Like all good romances, Pioneer Summer does this by creating credible characters who elicit readers’ empathy. At their forefront stands Yura, whose journey twenty years into the past and deep into Ukraine brings him to the time capsule that he and Volodya buried on their final, passionate night of summer camp. By framing the novel with Yura’s quest for lost love and allowing its narrator omniscient access to only Yura’s mind, Malisova and Sylvanova create a compellingly complex character, whose multilayered viewpoint slides from adolescent angst to grief over childhood loss, sexual self-discovery, and mature self-acceptance. In contrast, the slightly older Volodya, to whose mind the reader has no real access, remains an alluring enigma, as he first discourages Yura’s eager affection and then self-harms before embracing the younger boy. The novel’s secondary characters, for example, the lisping Pioneer enthusiast Olezhka and the maliciously jealous Masha, add texture and fun to its depiction of everyday life in a Pioneer summer camp, as does the authors’ painstaking attention to late-Soviet realia.

Both masterful and timely, Anne O. Fisher’s translation of Pioneer Summer successfully conveys the multiple registers of Malisova and Sylvanova’s prose, preserving the delightful quirks of its origins in fanfiction. For example, Fisher renders the acronym PUK, which Yura uses to refer to the meddlesome Polina, Uliana, and Ksenia, as “the Pukes,” a decision that cleverly conveys the three girls’ gossipy backbiting, which Yura so detests. Moreover, Fisher successfully communicates the many nuances of the Young Pioneers, such as the all-important red neckerchief, and handles the novel’s Ukrainian setting sensitively by rendering place-names in Ukrainian and not Russian.

As Putin’s inhuman war in Ukraine drags on, Fisher’s translation of Pioneer Summer seems particularly opportune. Not only did the novel, due to no fault of its authors, act as the trigger for Russia’s repressive anti-LGBTQ+ law, but it also gives us perhaps the clearest picture of what Russian readers would read if they could. Pioneer Summer’s best-seller status suggests that many in Putin’s Russia are hungry not just for stories about love but, more importantly, that provide a rich depiction of the vulnerability and intimacy that two men can share. Just as important, those who snatched Pioneer Summer from Russian bookstores appear to appreciate subtle representations of Ukraine as a place that can foster not only love but also tolerance, inclusion, healing, and imagination. Fisher’s translation of Pioneer Summer provides those who do not read Russian with a much-needed glimpse behind Putin’s toxic homophobia and xenophobia to see what other Russians read and how some Russians would love.

Julie Cassiday

Williams College