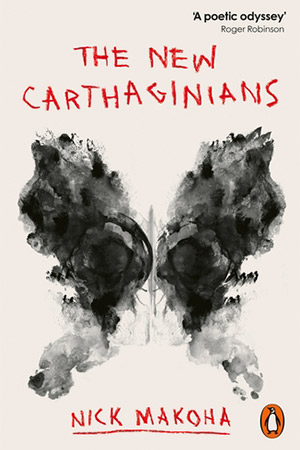

The New Carthaginians by Nick Makoha

London. Penguin Books. 2025. 112 pages.

Sometimes poetry does not just precipitate in descriptions. Jean-Michel Basquiat went beyond the obvious and layered his complex paintings, creating a codex displayed as a collage, bold in colors flaunting his unique selection of symbolisms to make a political and cultural statement, to mark a unique identity to discover who he was, where the fragmented text also played its part in his graffiti.

Nick Makoha’s experiment borrows from this art and takes us to his defragmented world to coalesce “the other” emerging from the raid on Entebbe Airport in 1976. While this event is present at the surface level, Makoha’s flight from Uganda after the event leads him to visit the complex lace of cultural, linguistic, and mythological sensitivities in his collection The New Carthaginians. On his morphological canvas, he explores the codex of not the ekphrasis perceived but a “double ekphrasis,” arising from the sublayers evolving at the distances of secondary meanings; he uses Basquiat’s technique of “exploded” canvas on the Operation Thunderbolt. “And in this reality, the trap is to believe in just the facts.” It explains the poet’s quest not to create a poetry of reportage but a poetry of fragments that tries to decode and makes the poet understand more about his identity concerning old and new myths.

With extraordinary originality, Makoha, a winner of the 2021 Ivan Juritz Prize and the Poetry London Prize, leaps in this book to the ambiguity of a codex to deconstruct it and then reassembles it through neo-myths, language, history, philosophy, and collage created by the imaginary poet signing off as CODEX©, just like Basquiat signing off as SAMO©. But to craft the neo-myth, as Makoha says, “By retelling the myth, (inadvertently) I am creating a new myth. In this case, the third player is Icarus, common to both Basquiat and CODEX©. But this Icarus is black!” Why? “Icarus was ambitious (and took risk).”

According to Makoha, Icarus and his flight reflect his life. He, too, wants to be adventurous and tell his contemporary and parallel story as he is Black. He asks during the flight, “How I got here? Am I of this world or that world?” This finds juxtaposition in the plane that arrives to raid Entebbe. The poet wonders about the plane and the flight. When he flees Uganda, he is also on a different flight. Therefore, the question arises of who this Black Icarus is. The poet tries to decodify this codex, which holds the complex identity crisis of a Black culture where “it is a proxy culture.”

The contextuality of chronological occurrences of the raid unfolds in terms of three characters superimposed to look like one, as in Basquiat the images and text try to do just that. ‘The Uganda summer of ’76 sits in the centre. / . . . / Black-winged Icarus, the first container, will be our mythology. / Basquiat, the second container, will be my imagination, the new Hi-Tek the new / Bitek.” The flight in the background is not only his, of Operation Thunderbolt, or even of the rescue, but it is of Black Icarus.

He finds it intriguing that in these events, the story for the world is not about Africa. In the recounting, it is also not about Arabs and Israel. It is as if Africa is irrelevant and erased. Time itself assumes itself to be surreal! Only the hostages matter. But one forgets that Ugandans like him, who are hostages of African history, are also forgotten. That cultural crisis surfaces: “Neither did I choose the ceiling of stars that made me a foreigner that evening.”

I will be surprised if this book doesn’t win many awards. (Editorial note: Read Makoha’s “Icarus Asks Basquiat to Paint Him”)

Yogesh Patel

London