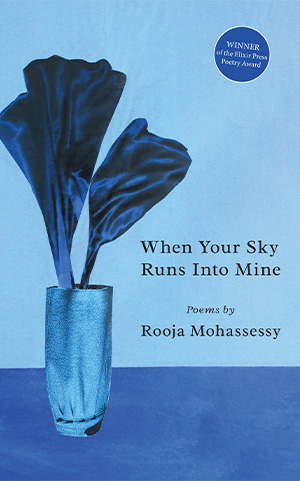

When Your Sky Runs into Mine by Rooja Mohassessy

Denver, Colorado. Elixir Press. 2023. 116 pages.

Denver, Colorado. Elixir Press. 2023. 116 pages.

It is an immensely personal thing to make a literary debut. Rooja Mohassessy embraces the vulnerability of this journey with a beautifully crafted collection of poetry, jeweled with imagery and phrases that illuminate vivid emotion. The Center for Iranian Diaspora Studies (San Francisco State) first introduced this captivating new release to me, and I was afforded time to converse with the author herself. Mohassessy was born in Iran and, during the eight-year-long Iran–Iraq War, was sent abroad permanently to live with extended family. This brief childhood in Iran would later be carefully coaxed out of Mohassessy’s memories with access to her uncle’s striking artwork. Mohassessy was close with her uncle, Bahman Mohassess (1931–2010), a prominent contemporary artist in Iran whose sexuality stigmatized him, forcing him into exile. She lived with him for a time in Rome, where he spent the remainder of his life; she attributes her embraced artistry to their relationship.

When Your Sky Runs into Mine is roughly hewn into four segments—seasons—of a life moving forward. Mohassessy’s ekphrastic poems meditate on a personal, surviving portfolio of her uncle’s collages. In the first portion of the collection, there is an acute observation of the suffering and change that accompanies war. The opening poem of this section and the book as a whole, “Iran Politics in First Grade,” creates a nightmarish vignette of uncertainty that, like memories themselves, display the delicate origin of the narrator:

The television is louder. Inside

it grownups

bang into one another like flies

caught

in a flytrap, their mouths agape with static.

From these verses on, Mohassessy teases out the discomfiture of being folded into fabrics for public spaces and the young generation lost to weaponized chemicals, emotions that blend into the following sections where she explores the growing pains of an untethered life, the guilt and lament, envy and silence of “The Immigrant.” The final two sections are more robust in form, gaining space and agency with a life lived thoughtfully. It strikes me how skillfully Mohassessy pairs words together, harmonizing their sound and imagery. The end of this debut collection is found in the final four verses of “My Only Bangle,” a poem dedicated to her great-grandmother:

Here, it whispered, rub some kohl

under your eyes before you

step out,

then let me hear you

pronounce your name.

Here, it strikes me, is the unrelenting treasure of an ancestry under fire. Rooja Mohassessy was born in the peak of Iranian political turmoil, and today Iranians are born into bloodshed, disguised in a different time. To me, this is an ending that leaves room for another beginning, a salve to the child with whom we began this collection sitting in the first grade. Now, it whispered, let me hear you pronounce zan, zendgi, azadi.

Taylor Nasim Stone

San Francisco State University