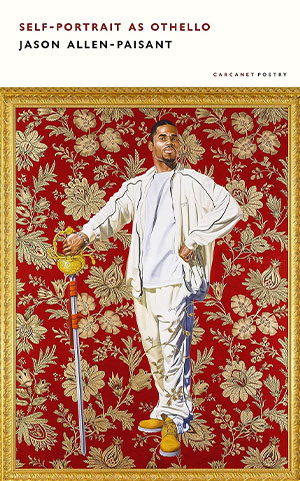

Self-Portrait as Othello by Jason Allen-Paisant

Manchester, UK. Carcanet Press. 2023. 80 pages.

Manchester, UK. Carcanet Press. 2023. 80 pages.

As the title would suggest, Jason Allen-Paisant’s Self-Portrait as Othello is an examination of the poet’s person, rendered alongside—and, at times, in contrast with—the image of Othello from Shakespeare’s eponymous play. And with this central framework, Allen-Paisant carefully, passionately traces a life story of absence, romance, identity, incongruity, and, ultimately, self-acknowledgment as a Black man.

One of the more scintillating qualities of Self-Portrait is Allen-Paisant’s integration of multiple languages. In traversing tableaux of parental longing in Jamaica’s Coffee Grove, awkward romantic engagements in Paris, libertine escapades in Oxford, and much more, Allen-Paisant seamlessly accents his verse with sprinkles of patois, French, Italian, and German. In this way, he achieves greater reader immersion and avoids the rather unfashionable clumsiness of translation. Each of these languages appears to correspond as well to one of Allen-Paisant’s “modes” throughout Self-Portrait, with patois being used primarily to express feelings of abandonment or vulnerability, French: sex and sorrow, Italian: glory, Othello-ness. This mixing of languages is just subtle enough to enhance one’s reading experience without coming off as obfuscatory or shallowly dextrous.

Just as impressive as Allen-Paisant’s lingual feats is his attention to artistic and historical contexts while connecting himself to Othello. Othello, naturally, is a fictional character, but in drawing on sources like Dionne Brand’s A Map to the Door of No Return and Original Journals of the Voyages of Cada Mosto, and Pedro de Cintra to the Coast of Africa (compiled by Robert Kerr), Allen-Paisant delves into the documented presence of African Moors in Italy and the idea that “the Black body. . . is open space” (Dionne Brand) that can be occupied by others beyond the self—in this case, Allen-Paisant and Othello simultaneously. In the book’s second section, particularly, the connections to the valiant, misunderstood Othello appear more tangible, inhabited. Beyond this, references to works like Lemoyne’s Phèdre, Severini’s Sea = Dancer, and Veronese’s The Feast in the House of Levi add depth and offer jumping-off points for further considerations of the book’s crucial themes.

Jason Allen-Paisant’s Self-Portrait as Othello whisks its readers along like a confident lead (there is much dancing-related imagery to enjoy throughout), offering rich descriptions, lingual agility, and poignant social criticism along the way. With the exception of one or two slightly self-indulgent anatomy-focused poems near the end, Allen-Paisant has succeeded in crafting an engaging, layered collection that transcends the poetic memoir genre and demonstrates the value of intersectional perspectives.

Aaron Barry

Vancouver