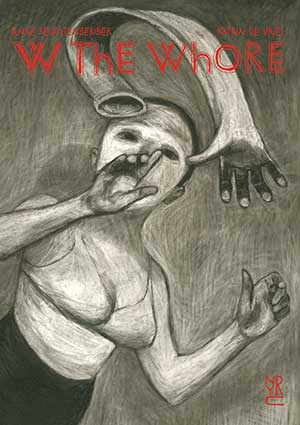

W the Whore by Anke Feuchtenberger & Katrin de Vries

New York. New York Review Books. 2023. 254 pages.

New York. New York Review Books. 2023. 254 pages.

W the Whore consists of three graphic novels originally published in Germany in 2001, 2003, and 2007 and now considered a classic in the genre, with a foothold in both graphic and feminist literature (see WLT, March 2016, 50). The trilogy follows an archetypal female figure navigating the mythical and mystifying waters of womanhood. The passage is haunted by fantasies of fulfillment and the false promises of self-awareness and self-realization but also brightened by rude awakenings, oracular insights, and a premonition of what may be called enlightenment by disillusion.

Each of the nine episodes sees the heroine engaged in a quest for something (desire, feeling, freedom, love, marriage, childbirth) that will prove fallacious and unattainable, at least based on the common expectations of society and culture (with biology lurking in the background). The result is a postmodern, postfeminist fairy tale, as fresh and captivating today as it was when it first appeared some twenty years ago.

The writing is minimalist and matter-of-fact, occasionally vetero-testamentary in tone (“And the man desired W the Whore. . . . And soon, the man had desired W the Whore”) and perfectly matched by compelling graphics that enhance the text, expanding its narrative drive and adding layers of meaning to it. Each of the three original books is distinguished by a significant change in style, from the sharp and hatch-textured draftsmanship of the beginning, to the increasingly caliginous sfumato of the middle section, and the dark and dense brushwork that swallows everything at the end. This progress is consistent with the growth and evolving appearance of the protagonist, who is depicted as a puber-punk in the first three episodes; a searching young woman in the next three; and eventually a middle-aged, power-seeking lover in “The Lighthouse,” an unfulfilled and cynical single mother in “The Court” (wearing a black dress and a Jackie O hairstyle), and a supposedly aged woman in the final episode, “The Ballroom,” where her figure is barely seen, until the jaws of darkness devour it up.

No less eloquent is the evolution of the landscapes, their painterly references (from the metaphysical corners of Carrà and de Chirico to the bleak, urban labyrinths of German expressionism) and their symbolic features, with recesses, holes, and subterranean chambers providing a feminine counterpart to the more obvious phallic tower and lighthouse. As a critique of both the eternal feminine and mainstream feminism, W the Whore stresses the importance and the value of imagination and creativity over social analysis and commentary. This (and the quality of the writing and the artwork) raises it above most “engaged” graphic literature of today, which is too often literal and didactic. A translator’s note and an interview (by Madeleine Schwartz) with the authors provide valuable information on the collaboration between writer and artist, the origin of the series, and its cult following.

In the end, W the Whore may never find what she is looking for, but when she meets R the Reader, it is love at first sight.

Graziano Krätli

North Haven, Connecticut