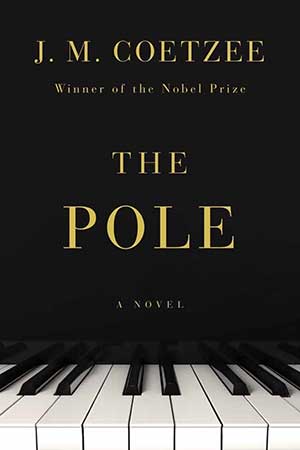

The Pole by J. M. Coetzee

New York. Liveright. 2023. 166 pages.

New York. Liveright. 2023. 166 pages.

In music, when one wants to sound impressive, it’s best to play something fast; prestissimo gets the audience’s pulse up. If what is desired, however, is to play impressively, one must play something slow. Without the distraction of speed, the protective flurry of notes, your musicality—your artistic competence —is laid bare. With The Pole, J. M. Coetzee is playing (writing) as slowly as possible.

The story is simple: a romantic tangle between Beatriz, a Catalan woman in her late forties, and Witold Walczykiewicz, a Polish concert pianist known for his offbeat interpretation of Chopin. Beatriz, married to a busy and adulterous banker, spends her days at “good works” in Barcelona’s cultural scene. Though she is dull, if not a little cold, after a single meeting, Witold, a divorcé in his seventies, is smitten. Thus commences a long, rather lackluster, courtship.

Both characters are laid down like thin leaves. We learn little of them beyond how they react to the situation at hand, which rolls out in brief, numbered paragraphs, some as short as one sentence. The scenes are minimal, at times merely suggestions. (“It is a pleasant autumn day. The leaves are turning, et cetera.”) If it feels skeletal, it is because the bones are visible: it is a clear retelling of the story of Dante and Beatrice; Beatriz is even gifted a book of poems, a Vita Nuova, from her admirer.

Dante’s ode to Beatrice is considered one of history’s epic love stories, a testament to the power of emotion and art. But it is Dante’s version. Told from the perspective of the muse, as Coetzee does here, the romance is something more like Susanna and the Elders: unwanted, unreciprocated, teetering on lechery.

Unrequited relationships, especially between decrepit males and stern, astute women, are a regular Coetzeean theme—as are the limitations of language. When our Spaniard and Pole communicate exclusively in English, they cannot help but feel themselves lost in interpretation. Thinks Beatriz: “It is sometimes hard to know what the man means, with his incomplete English. Is he saying something profound, or is he simply hitting the wrong words, like a monkey sitting in front of a typewriter?”

Translators only confuse the matter, adding a layer of complexity to the words. “I translate your poems for you, and then you decide what they mean,” a Polish-Spanish translator tells Beatriz, who wants to skip subtlety and go straight for the throat. Nuance, when we long for clarity, is infuriating. Language, nationality, age: is art not the bridge over which the gulf of communication caused by these differences may be crossed?

Over fifty years of published work, Coetzee has concerned himself with the ethical potential of fiction and the role of the artist in the public sphere. In The Good Story, Coetzee describes the artist as the one who “is supposed to have the power to find the words for what is wrong, or what has gone wrong, or what we have done wrong.” Yet all of Witold’s attempts to communicate anything through art fall short. Beatriz finds his Chopin too dry, his poems too obtuse; he is lacking in ardor. The art that exists between the two, like their conversations, remains measureless, like “coins passed back and forth in the dark, in ignorance of what they are worth.”

The Pole addresses this failure, and the role—and effect—of the artist in the personal lives of others. It is first a question of proximity. To some, Witold is “Maestro,” a master of music. To those outside the realm of his chosen art, he is a nobody. It is his tragedy that to those closest to him, those he longs to reach—his ex-wife, his daughter, his neighbor, Beatriz—he is a nuisance, pretentious, too abstract.

The people of Coetzee’s books are for the most part what would be called intellectuals. With a few notable exceptions, there is never much action, but a whole lot of thinking goes on. Again and again, Coetzee suggests their troubles are born by a failure to communicate what is in their heart, in their soul. Their intelligence, in this respect, might be their impediment. They reflect, they analyze, they brood, even if an “excess of reflection can paralyse the will.”

This is a preoccupation of Coetzee the man. In his autrebiography Youth (2002), Coetzee wrote of preoccupations with either/or paths being burnt into the brain, of a failure to write “from the heart.” Through Witold’s struggle throughout The Pole, one feels it may still be an issue for the author, one exacerbated by notoriety: “The airports, the hotels, all different yet all the same; the hosts to put up with, all different yet all the same: gushing middle-aged women with bored attendant husbands. Enough to quench whatever spark there is in the soul.”

Coetzee casts his intellectuals and artists into situations where thinking alone will not suffice. They must act. Often, they misjudge the situation and those around them. They fail at the most basic relationships, are left excommunicated, defeated, alone. Intellectualism—and, by proxy, art—may be deemed good or great at a distance by admirers. Where they fail is in intimacy, where more is required of a person than abstraction and idealism.

Art, it seems, is not a labor of joy for the artist himself. In 2000 Coetzee was interviewed by Dutch journalist Wim Kayzer for the television program Van de schoonheid en de troost (Of Beauty and Consolation). “Writing in itself is neither beautiful nor consoling,” Coetzee said. “It’s industry. It has its own pleasures, which are the pleasures of total engagement, hard thought, verifiable activity, verifiable results. Productiveness. . . . Beauty and consolation belong not to the activity but to the results of that activity.” In other words: “My finished work may bring contentment, but I, while creating them, will not.”

“Art is a jealous mistress,” said Emerson in Wealth. “If a man have a genius for painting, poetry, music, architecture, or philosophy, he makes a bad husband, and an ill provider, and should be wise in season, and not fetter himself with duties which will embitter his days, and spoil him for his proper work.”

Genius notwithstanding, art is notoriously destructive, consuming, fickle, insecure. It fosters those qualities in its creators. In that sense, The Pole reads like a follow-up from Summertime (2009), wherein Coetzee the writer lambasts Coetzee the character as a “Loner. Socially inept. Repressed,” among other home truths. Witold is not wholly distinguishable from Coetzee, who is gently tacit regarding his private life. (Witold’s austere, Bach-like interpretation of Chopin reads like a credible self-review of Coetzee’s prose.) One is left to wonder about an artist in the winter of his years, lauded with the highest awards and honors in his field. Were his artistic interpretations enough to convey what was in his heart to those closest to him? If nothing else, he is consistent to his distant audience. With The Pole, Coetzee, ever enigmatic, plays slowly, deliberately, with a delicate nuance that continues to impress.

J. R. Patterson was born on a cattle and grain farm in rural Manitoba, Canada. He has worked as a farm laborer, factory worker, and writer. He has written for a variety of international publications, including National Geographic, Literary Review of Canada, and LARB.

J. R. Patterson was born on a cattle and grain farm in rural Manitoba, Canada. He has worked as a farm laborer, factory worker, and writer. He has written for a variety of international publications, including National Geographic, Literary Review of Canada, and LARB.