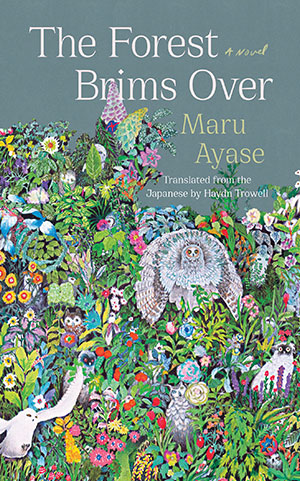

The Forest Brims Over by Maru Ayase

Berkeley. Counterpoint. 2023. 208 pages.

Berkeley. Counterpoint. 2023. 208 pages.

Maru Ayase (b. 1986) is a well-established author with numerous novels under her belt, but the work under review is her first to be translated into English. The premise is intriguing, yet the execution will undoubtedly strike some as insufficient to the task of realizing that potential. Thus, despite being a contender for the Oda Sakunosuke Prize upon its publication, 2019 must have been a very thin year for literature if we are to believe the words in the “advanced praise” blurb claiming that The Forest Brims Over is “the most impactful book of the year.” Neither, however, is it a failure, for Ayase tackles problems anything but unique to Japan: rampant male chauvinism, sexism in the workplace, and the deep desire for acceptance of who one is. Indeed, its strength might lie in the very ambiguity of its conclusion.

The story revolves around a philandering author, Nowatari Takao, and his wife, Rui, who is his thanklessly exploited muse and who homophonically gave her name to his first novel, Tears. Nowatari is comfortable ignoring Rui’s feelings because she “was a woman [and] he bore an implicit prejudice against her.” Perspective is supplied by two literary agents who must contend with the fallout of Takao’s affair with a student, which drives Rui to transform into a lush, expanding forest that overgrows their bedroom and seemingly spills out beyond the walls of their home. This world-within-a-world serves as both refuge and terra incognita. It is precisely this “unknown” dimension that will occasion the disillusioning resolution with which the novel concludes. Fed up with Takao’s inability to write a new novel, Shirasaki, the second agent to try to coax some product out of the stagnating author, demands that he enter the forest and confront what it offers.

Before addressing the dénouement, it is worth considering the writing. Haydn Trowell’s translation is accurate and captures the feel of Ayase’s prose; however, her prose is marked by the occasional odd phrasing that proves distracting. Moreover, Ayase seemed engaged in some grand metaphor contest that required of her countless attempts at creating the one locution that was sure to remain forever with her readers, a stylistic fillip that proved jarring more often than illuminating.

Despite the implicit promise Ayase offers of liberating women from the bonds of a male-dominated world that sees them as “dead weight,” the ending appears a disappointment, primarily because it suggests that the solution is reconciliation in which women seem to have some role greater than that of a simple cipher, but still exist within the patriarchal structures against which the novel putatively inveighs. Ayase’s challenge to the reader is that this conclusion might be a mistake. The fact that Rui seems to have returned, in some measure, to her prior role may actually be the far less optimistic point Ayase is trying to convey. Rui confirms that no amount of effort, even that aided by magic, will alleviate the condition of women in Japanese society. Of course the forest brims over with tears.

Erik R. Lofgren

Bucknell University