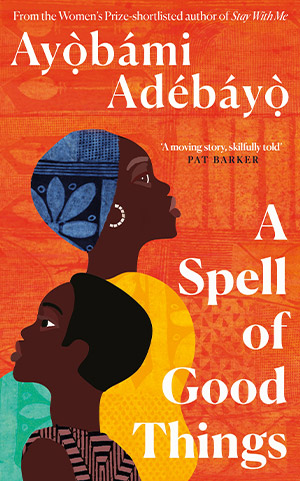

A Spell of Good Things by Ayobami Adebayo

New York. Knopf. 2023. 352 pages.

New York. Knopf. 2023. 352 pages.

The phrase “that’s just what you do,” spoken by the protagonist’s mother in part 1 of Ayobami Adebayo’s A Spell of Good Things, takes on layers of meaning as the novel navigates various structures of hierarchy and power. Though seemingly offhand and simple, the words epitomize the questionable decisions the novel’s protagonists make to acquire or maintain livable conditions within the social structures that ensnare them. They also seem to anticipate or, more accurately, to deflect any potential resistance.

Wúràọlá and Ẹniọlá, the novel’s two main protagonists, inhabit adjacent though profoundly different worlds: Ẹniọlá works for the tailor patronized by Wúràọlá’s mother. Wúràọlá is a twenty-eight-year-old medical student, the “golden child” older daughter of a wealthy and powerful family; he is the sixteen-year-old firstborn of what used to be a middle-class family, now destitute and reduced to begging after their father, a former teacher, was laid off as part of a large-scale defunding of public education. Despite the differences in their material realities, both struggle to fulfill personal and culturally prescribed ambitions. Ẹniọlá’s dream of upward mobility is made possible by education but seems thwarted at every turn by his family’s poverty. He feels both resentful of their circumstances and duty-bound to their survival, for which his mother increasingly makes him responsible. Meanwhile, Wúràọlá, afforded every opportunity to succeed in her education and profession, is perpetually exhausted by the demands of practicing medicine in an underfunded health-care system. Moreover, the escalation of violence in her relationship with the aspiring politician’s son, Kúnlé, forces her to choose between her physical safety and the expectation that she marry well before she ages out of being considered “marriageable.”

The protagonists’ respective dilemmas expose how contemporary life normalizes certain kinds of violence, how hierarchies of power maintain themselves through such normalization, and how ill-equipped the modern nation-state is to provide its citizens with functional systems that support basic needs such as sustenance, health care, and education. For Wúràọlá, it’s easy to see how the social violence of patriarchy, reproduced within the family hierarchy and its attendant expectations regarding her future, lead to the physical violence Kúnlé inflicts upon her. “That’s just what you do” could refer to anticipating your boyfriend’s hunger and offering to serve him lunch, or it could convince Wúràọlá to accept his violence as a sacrifice required to be successful in achieving the status of wife.

In Ẹniọlá’s case, the less humanely he is treated—from being spat on for trying to steal a newspaper so his dad could search for a job to being flogged by the headmaster in front of his class for not being able to afford his school fees—the more detached he becomes from his own humanity. This shift allows him to justify working for a corrupt politician, one who exploits poor and desperate boys like him to carry out morally questionable tasks, boys who will do whatever is asked of them because “that is what you do” when you’re hungry. Both Wúràọlá and Ẹniọlá spend the novel responding to systems of oppression against which they have little power, and each attempts to create certainty for themself in their own way, however questionable that might be.

Overall, A Spell of Good Things succeeds at the formidable task of following Adebayo’s powerful debut novel, Stay with Me. Like its predecessor, A Spell of Good Things proves masterful at detailing the complex inner workings of human nature and eliciting empathy for its multidimensional characters. Also like Stay with Me, it dramatizes the ways that structural violences inevitably intrude upon all interpersonal relationships, though A Spell of Good Things is far more overtly invested in exploring the cultural and political cruelties shaping all of our lives. This final point is what makes A Spell of Good Things particularly powerful: although Adebayo’s critique of these structural inequities is anything but subtle, she renders them in an achingly candid way, at once specific to the context of contemporary Nigeria and also painfully, if not unsurprisingly, familiar to any modern reader.

Ann Marie Short

St. Mary’s College