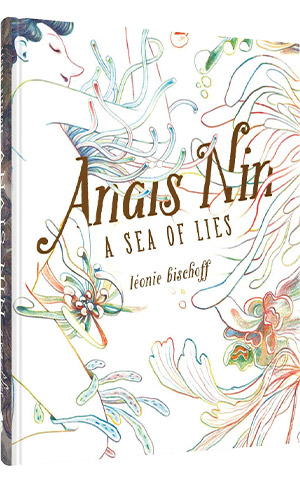

Anaïs Nin: A Sea of Lies by Léonie Bischoff

Seattle. Fantagraphics. 2023. 184 pages.

Seattle. Fantagraphics. 2023. 184 pages.

Graphic biographies are a fairly new phenomenon, and the genre definitely has legs. Graphic form can constrain the narrative via the conventions of panels, speech bubbles, and thought bubbles. But there are myriad exciting possibilities for visual images to convey metaphor, character, and action.

In this gorgeously drawn graphic biography of Anaïs Nin, Léonie Bischoff outdoes herself in creating images that surpass even Nin’s statement that “our life is composed greatly from dreams, from the unconscious, and they must be brought into connection with action. They must be woven together.” Bischoff creates vivid scenes with her exquisitely drawn lines, distinctive colors, and phantasmagoric scenes. Nin comes alive on the page as her unconscious takes form in her interactions with a wide variety of people, mostly men, although, of course, there is always June Miller, Henry’s wife.

But let’s start almost at the beginning, as Bischoff does, with Nin and her husband, the rather prosaic Hugo Guiler, a banker and poet manqué who supports them and eventually Henry Miller. That the book begins with Nin already a married woman counters the form of most biographies, which often begin with the early life, but Bischoff fills in the blanks with flashbacks in Nin’s mind later in the book. Bischoff is most interested in Nin’s early adult life, which is about unleashing her dreams and desires. It is only in acting on these that Nin can realize her potential as an artist.

Anyone who has read Nin’s diaries knows that her intense focus is on passion and the erotic life. And, indeed, this biography begins with images of enormous breaking waves after which we see Nin curled on the floor surrounded by notebooks. She is spent but rallies enough to attend an evening soirée as the dutiful wife. There, in the opening pages, we see the essential conflict in Nin’s life between her orientation as an artist and her mundane life as Hugo’s wife.

Bischoff masterfully depicts Nin’s duality—the demure, perfectly coiffed wife contrasted with the yet-to-be-unleashed sexy woman with wild, plentiful multicolored hair. If only Nin could let her hair down! And she does, in her flamenco lessons, her psychoanalysis sessions, her conversations with her cousin Eduardo, and then, most explosively, when she meets Henry Miller. At that point in Nin’s life, she begins to let loose, artistically and sexually, and Bischoff treats this transformation with color-saturated illustrations that might populate fever dreams.

Henry Miller serves as Nin’s muse as well as her lover, and, as with many of the men in Nin’s life who would like to define her, Miller, in the role of editor, would like to revise Nin’s writing. Although he unleashes her sexuality, Nin’s thought bubbles above their sexual encounters are often filled with rather flat clichés: “His movements are forceful but gentle,” “The pleasure leaves me wordless.” The drawings are beautifully sensual and clearly sexual without being pornographic, but Miller is not the absolute answer to Nin’s dilemma. Miller’s wife, June, who enthralls Nin, is portrayed as an apparition, and the lush drawings of her are extremely sensual yet elusive. We are never certain whether the strong attraction between June and Anaïs is consummated, but the erotic energy between them is explicit.

The psychological complexity of Nin’s many romantic and sexual relationships is never fully explored, and it is difficult to imagine how they could be within the structure of a graphic biography. Clearly, this is not an analytic biography but rather an overview of Nin’s creative struggles. She is portrayed as oddly innocent and yet sexually voracious—she sleeps with her analysts, her dance teacher, her maybe homosexual cousin, and even her father. Doubtless, Nin was a complicated woman and catnip to a variety of men—but there is a definite creepiness about her adult sexual encounters with her father in her attempt to heal her childhood trauma. In the end, Nin’s own self-analysis is far too naïve and simplistic for my taste: “I am a mirror for the desires of men. And the roles that I play for them ignite the fire of their creativity.”

It is too much to expect that this graphic biography could be as nuanced and complete as a traditional prose volume. But in this nascent genre, Bischoff sets a high standard by brilliantly capturing Nin’s creation of herself as an artist. She not only whets the appetite of anyone who wants to delve further into Nin’s work, but her pages also shimmer with the artistic abandon Nin sought in her own work.

Rita D. Jacobs

New York City