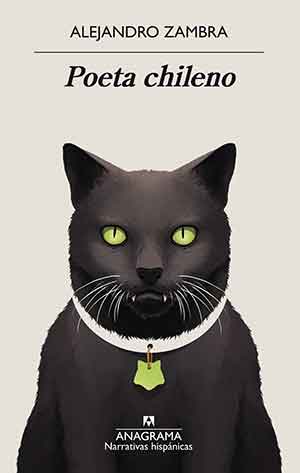

Poeta chileno by Alejandro Zambra

Barcelona. Editorial Anagrama. 2020. 421 pages.

Barcelona. Editorial Anagrama. 2020. 421 pages.

ALEJANDRO ZAMBRA—who frequently expounds on why the Great Latin American Novel will be distinguished by its poeticity and keeps garnering worldwide prestige with his short novels, stories, and nonfiction—has published a brilliant poetical novel that is not strictly “Latin American.” Like Bolaño, his only peer, he started as a poet in a country overrun by Nobel Prize–winning poets and wannabes and never lets the cat out of the bag. The framing story centers on Gonzalo, an aspiring poet and stepfather to Vicente, a child addicted to cat food (the cover’s black cat is called Obscurity) who later refuses to go to college because his dream is to become a poet.

A topsy-turvy blend of bildungsroman and roman à clef, Poeta chileno, a title heaving with allusions and semantic charges, amends the poetics of contemporary “autobiographictions,” verifying the need to renovate their validity. Zambra does so by brilliantly coaxing his readers in each of the novel’s four parts to believe his frequently hilarious tales, faithfully reproducing various speech registers (English included), and by infusing the poetization of his novel with profound questions about history, pop culture (mainly musical), and especially literature from all the Americas. The cumulative effect of this cultural wokeness endows the novel with a distinctive yet recognizable precision and reliability.

The particulars and symbolism of poets’ misfortunes differ from tale to tale, so Zambra commingles them with a realist bookish gaze in a mash-up devoid of ellipses, subtly handling layers of circularities and recurrences to underline the poets’ or their detractors’ shortcomings and hollowness; in Gonzalo’s case, his relationship with Carla (Vicente’s mother) and León, her former husband. To reconcile themselves with poetry, in “Parque del recuerdo” (Remembrance Park; Santiago’s cemetery), the final part set in Brooklyn and Santiago, stepfather and stepson discuss books or authors read and unread, with Vicente’s poetry interspersed. For such inflections and intellectual enthusiasms, the American Ben Lerner is the only eminent author who approximates Zambra’s comprehensive take on the genre.

The second (“Familiastra,” Stepfamily) and third (“Poetry in motion” in the original) parts are the most extensive, with the latter introducing Pru, an initially naïve American cultural journalist who in exchanges with Vicente (her “translator” of Chilean speech before they split), Pato, Virginia, and others provides an accounting of the poetry scene. The characters (among them Prof. Rocotto, a priggish poetry “expert” uninterested in Nicanor Parra!) have different stakes in the vetting of the genre, its usefulness, and practitioners. Many of their comments—like “anthologies are the phonebooks of new poets,” a comparison they may not understand because “they grew up in a world in which phonebooks were disappearing” (the time is after 2014)—are pithy, or sarcastic, as when Pato says, “Zurita beats the shit out of all of them, because he is the true people’s poet.”

What links these souls is infrequent empathy, not poetry’s angst, the gist of the second part. In that part Gonzalo has written Parque del Recuerdo, in two months, and will self-publish it probably with one of the synonyms he had thought about in the first part—Gonzalo Rimbaud, Gonzalo Ginsberg, Gonzalo Pizarnik, Gonzalo Lee Masters—before leaving for New York to finish a doctorate. A different narrator says in the first part’s last page, “nine years later they saw each other again, and thanks to that reencounter this story reaches the number of pages necessary to be considered a novel”; reappearing in the novel’s very last page to speculate on an optimistic end, to the point of his feeling “like writing until I reach a thousand pages.”

There are recurring themes in Zambra’s fiction, but he always takes risks and refuses to placate identity politics, despite Rita’s saying to Pru that the world of Chilean poetry is slightly better than Chile, which is “class-conscious, machista, rigid.” Thus, when James Wood returns to praising his fiction in the revised edition of How Fiction Works (2018), he places Zambra alongside Ali Smith, Knausgaard, Ferrante, Lydia Davis, Roth, Saramago, and Beckett, whose works “comment on story-making and which are, at the same time, intensely invested in the world we inhabit.” But the Latin American tradition is larger than Wood’s world literature corpus, with the Chilean at its forefront. Possessed of a great critical mind and abundant readings in world literature, as Not to Read (2018) displays authoritatively, he shows that it is better to read one’s models or masters well than disguising who they are.

For the canonical critic Ignacio Echevarría, Poeta chileno is not a novelistic epigone but primarily a charming, very rare, and disconcerting tribute to the poet’s vocation; a poignant settling of scores (in the third part Pato says, “He wasn’t a great poet, Bolaño”). The reception is equally enthusiastic in Spanish-language publications that are decisive in evaluating current literatures. For El País, the novel is “exemplary, humorous, and moving”; and in Letras Libres, Rodrigo Fresán, his contemporary, sees it as “The Great Chilean Novel about The Poetry of his generation.” It is also one of the two masterpieces of this century by his selected cohort, and Zambra is just getting started.

Will H. Corral

San Francisco