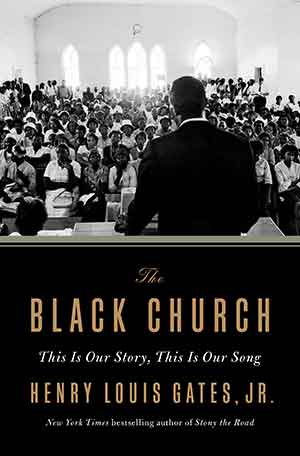

The Black Church: This Is Our Story, This Is Our Song by Henry Louis Gates Jr.

New York. Penguin Press. 2021. 304 pages.

New York. Penguin Press. 2021. 304 pages.

THIS WORK IS A wonderful addition to the recent scholarship that reevaluates the role of the Black Church in the development of African American (and by extension American) society. From religious studies to literature, scholars are highlighting the Black Church’s contributions that extend beyond the obvious source of spiritual comfort in troubling times. This work derives from research and interviews Henry Louis Gates Jr. conducted for a forthcoming PBS series by the same name. It combines historical accounts, interviews, photographs, illustrations, and Gates’s own personal narrative to demonstrate the long relevance of the so-called Black Church, which Gates makes clear early in the work “is diverse and contested.”

Like the Black experience itself, the Black Church is not one thing, and Gates provides, among other things, historical tracing reaching back to Africa, to the early republic, the antebellum period, Reconstruction, the Great Migration, the modern Civil Rights Movement, and the present. Consistently, the Black Church emerges in this work as a beacon of resistance, sustenance, activism, and communal care; in other words, it is “the cultural cauldron that Black people created to combat a system designated in every way to crush their spirit.” Paradoxically, the work also depicts it as a site of oppression and conservatism related to women and people of LGBTQ+ communities. Yet Gates’s work is inclusive of the many contributions of women, beginning notably with Jarena Lee’s persistence in her desire to preach, the recognition of women as the backbone of the church, and Prathia Hall’s “I Have a Dream” talk aloud with God, among others.

The discussion of Islam from the beginning of the abducted Africans’ forced migration to North America to the Nation of Islam’s influence during the modern Civil Rights Movement is fascinating. Other notable discussions include the historical bombings of Black worship houses as they were recognized as the seat of empowerment for Blacks. Gates’s discussion of the Jesuit scandal (indeed the role of the entire Catholic Church in the slave trade) involving slavery and their educational mission is riveting. Finally, his discussion on Black music (spirituals, gospel) as a requisite feature of the Black Church (along with sermonizing) is brilliantly executed and weaved throughout the account.

Framed by a very informative introduction and an epilogue that contains Gates’s personal recollections of the church, the four chapters are organized chronologically by key moments in American history. Chapter 2, “A Nation within a Nation,” is especially illuminating in its guide to the development of the Black Church. Likewise, chapter 4, “Crisis of Faith,” charts the decline of the Black Church as a force for transformation to its resurgence with new and powerful voices for both social change and accommodation to new musical styles and messages. Gates identifies hip-hop as “a new kind of secular ministry.” This is a brilliant work: a compelling read that incorporates little-known facts about the Black Church and clarifies other information held popularly by the public.

Adele Newson-Horst

Morgan State University