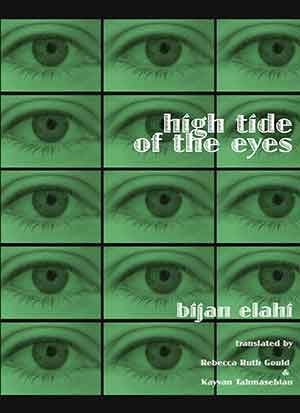

High Tide of the Eyes by Bijan Elahi

Brooklyn. The Operating System. 2019. 106 pages.

Brooklyn. The Operating System. 2019. 106 pages.

BIZHAN ELAHI (1945–2010) was not a prominent voice in Iranian poetry during his own lifetime. His relative obscurity might explain why High Tide of the Eyes, Rebecca Ruth Gould and Kayvan Tahmasebian’s dual-language Persian-English translations of Elahi’s work, appears in a series titled Unsilenced Texts. Elahi’s silencing as a poet, it should be noted, was of the self-imposed variety. Born into “a wealthy family,” as the translators introduce him, and a “perfectionist” who was “indifferent to fame,” Elahi never endeavored to publish a poetry collection, apart from a single 1972 poem cycle that was scheduled to run in two hundred copies but that he withdrew before the poems ever saw their way to print. It was only with the posthumous publication of two collections, Vision (didan) and Youths (javānihā), from which Gould and Tahmasebian have selected twenty poems, that the poet’s voice could begin to be more widely heard.

Elahi the translator, however, was not so reticent with his words. On the contrary, Elahi inserted his erudite and boldly experimental poetic voice into his many published and relatively well-received Persian translations of poets like Lorca, Eliot, Rimbaud, Hölderlin, and the ninth-century mystic al-Hallaj. Echoes of Elahi’s dialogues with other poetic traditions reverberate throughout the poems in High Tide of the Eyes and refract through Gould and Tahmasebian’s sensitive translations. Perhaps one of the collection’s best features is that it includes Elahi’s disparate statements on translation, drawn from various prefaces, introductions, and notes, so that readers can hear the poet-translator’s distinguished critical-theoretical voice as well. It is here that Elahi characterizes translation, which he calls “the repressed complex of creation,” as “a dance in chains,” an image that captures the constant negotiations between self-expression and formal constraints that are hosted within a poet-translator of Elahi’s caliber.

While Elahi’s dancer in chains might struggle to accommodate the demands of an unheard music, in his poetry it is through images, even more than sounds, that we come to experience his imaginative universe. Vision serves as the primary faculty for attaining meaning and the sense that awakens all the others. The poems in High Tide of the Eyes enact a kind of wandering contemplation and a thoughtful gaze, an observation for the sake of seeing itself. In “Dissecting an Onion,” it is the process of peeling layers that matters; there is no kernel at which to arrive, or, if a kernel exists, it does not reside within the object of dissection: “Without core, instead / labyrinthine. / What is a core, / if not the relation of the layers? / Centerless circles spiraling out / cut their relationships. / It is high tide of the eyes.” The Persian in that final phrase, madd-e binā’i, invites one to reflect on Elahi’s assertion in his introduction to Rimbaud’s Illuminations that “everywhere, everything can be defined in innumerable ways depending on the innumerable possibilities available in each situation.”

Here, madd-e binā’i could be translated innumerable ways, including but not limited to “the scope of seeing” (suggesting the poet’s play on the word madd as it appears in the expression dar madd-e nazar gereftan, meaning, roughly, to consider) or “the elongation of vision” (pulling toward another meaning of madd as a symbol denoting the long vowel sound ā). But the translators have landed upon the most poetically apt rendering, not only because madd can mean literally “high tide” but because the right kind of vision, the poem seems to say, is one drawn toward entities beyond the earthly and one that transforms the very performance, if not shape, of the eyes themselves. In Elahi’s dilated mode of seeing, vision covers a wider expanse while arousing the other senses in its wake; to watch an onion unravel into its layers is to feel the eyes washed clean.

Indeed, it is refreshing to take in the world from Elahi’s perspective, to sit in quiet contemplation, considering how “Wild grass / is wild grass. / Otherwise, it’s nameless.” In a different time, such musings may have been derided as “aristocratic poetry,” but today, one hopes, it is possible to think of artists and their art as inhabiting multiple spheres and realms. All attention in these poems turns toward words and things, words as things, the simplicity of words and the complexity of things. Elahi’s self-silencing suggests a certain type of quiet life, an advantageous view from a hilltop where one is left alone for such musings, unperturbed by the urban din beneath. It’s a privilege to join Elahi from such a vantage and to enjoy a freely wandering imagination from that view: “There you sit / atop a stone lion./ The lion gazes calmly, at the hill below.”

Samad Alavi

University of Oslo