Glasgow, City of Storytellers

GLASGOW IS NOT SO MUCH OF A CITY of books as a city of stories and storytellers. In the years I lived there, the stories I heard reflected the truly woeful conditions in which so many Glaswegians grew up; of filthy tenement blocks and binmen strikes, of bone-chilling winters and rat-catching, of the local variations on the kiss (a headbutt) and the smile (a knife slash to the cheek). In other places, these tales might form the basis for lessons about character or values, but in Glasgow, they were more often the premise for jokes. Glasgow is, despite everything—the low pay, the dreich (bad weather), the weekend fankles—a jovial place, one quick to laugh.

What is so confusing is that so many of Glasgow’s better times, usually considered to be when the Clyde shipyards and Singer sewing machine factory were in full swing, coincide with some of the city’s worst: its barest poverty, its foulest slums. Both the shipyards and the slums are gone now, leaving “The Dear Green Place” in a kind of stasis, being neither fully modern (hovering around fifty-five years, the life expectancy in the city’s east end is decades behind the rest of Europe) nor, with its plethora of vegan restaurants and modern sculpture, stuck in the dark ages.

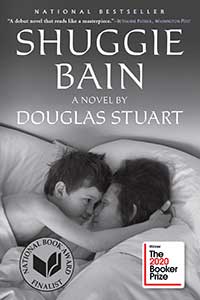

Of course, hard times persist. It’s for their evocation that Douglas Stuart’s Shuggie Bain was lauded and rewarded the 2020 Man Booker. There again times have changed. In 1994, when Glaswegian James Kelman collected the same honor for How Late It Was, How Late, his Scots-language novel about substance abuse and generational trauma was ridiculed and scorned by readers and publishers alike for being a literary sandbank.

Such thinking is completely glaikit, or stupid, as Kelman might write it. Much of it comes down to the language. Glaswegian, and the wider Scots language, is a form of English all its own, its meaning only possible to grasp in its echo, and sometimes not even then. It’s a sound even the Scots themselves, from the northern countryside to the English border, struggle to understand. Of his fellow Glaswegians, Kelman noted in his essay “The Importance of Glasgow in My Work” that “none of them knew how to talk! What larks! Every time they opened their mouth out came a stream of gobbledygook. Beautiful! Their language a cross between semaphore and Morse code.” Writers who chose to work in that local patois are often considered by English scholars to be nothing but literary oiks. But within the use of that rough vernacular is the understanding that language not only transcends form and tradition, it also shapes them.

Everywhere the Glaswegian is, the city is with him. Think of Billy Connolly’s two Glaswegians in Rome (hearing the Pope drinks crème de menthe before bed, they order two pints each. “The Pope drinks that stuff?” one says. “It’s nae wonder they carry him aboot on a chair!”). In the city, there are bookish sites—the baroque Mitchell Library, the Women’s Library, Alasdair Gray’s mural of roman-nosed nymphettes at the Hillhead subway station. Among the artists themselves, there is little literary tourism. If Glaswegians write well about hardship and want, it’s because it’s true to them. And any disregard among the growing self-refinement of British writing only proves its worth.

Of course, there are books to buy. The best are found within the bourachs of Caledonia Books, Thistle Books, and the Voltaire & Rousseau Bookshop, which are all on the scrubby banks of the River Kelvin.

What to Read on the Banks of the Clyde

Thomas Clark

Thomas Clark

Intae the Snaw

Gatehouse Press, 2015

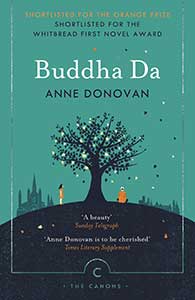

Anne Donovan

Anne Donovan

Buddha Da

Canongate, 2003

Alasdair Gray

Alasdair Gray

Poor Things

Bloomsbury, 1992

Archie Hind

Archie Hind

The Dear Green Place

Birlinn, 1966

H. Kingsley Long & Alexander McArthur

H. Kingsley Long & Alexander McArthur

No Mean City

Transworld, 1957

James Kelman

James Kelman

How Late It Was, How Late

Vintage, 1998

Douglas Stuart

Douglas Stuart

Shuggie Bain

Grove Press, 2020

Read Patterson’s essay on reviving Scottish Gaelic from this same issue.