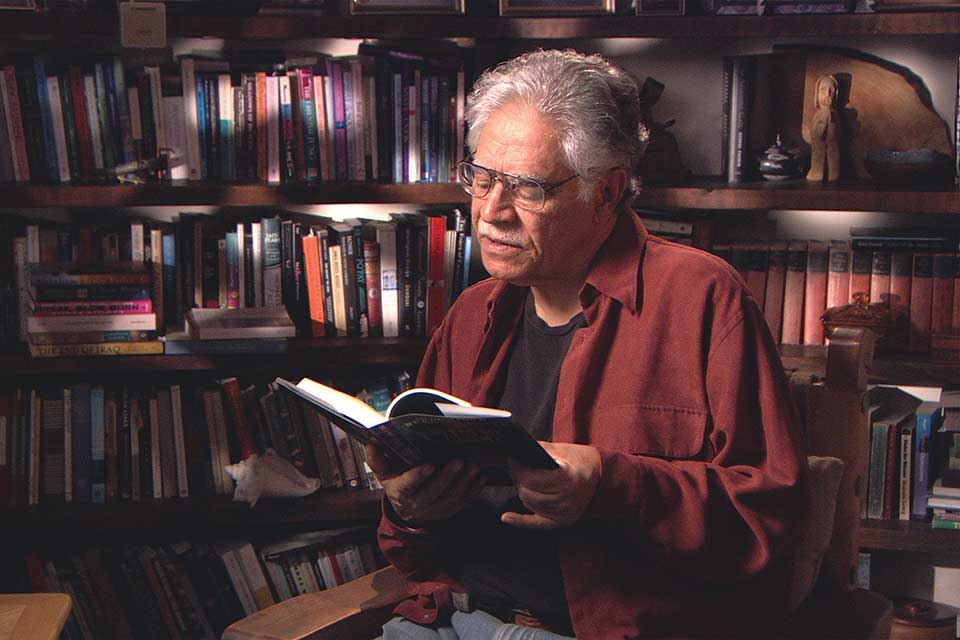

Rudolfo Anaya (1937–2020) A Reminiscence

In the following tribute, WLT’s executive director offers his homage to Rudolfo Anaya, both a legend of the Chicano Renaissance and a personal friend.

With Rudolfo Anaya’s death on June 28, 2020, World Literature Today lost a good friend—someone who published in its pages and liked to tell its director what he valued about each issue. For many more in the US and around the world, Anaya’s death marks the end of an era, the loss of yet another major figure from a generation of writers who became known as “Chicanos”—socially engaged contributors to the Mexican American experience. Often cited for his best-selling novel Bless Me, Ultima (1972), Anaya published some fifty volumes that range over novels, plays, poetry, essays, and children’s books. It will be said that during a crucial period in American history, he stepped up to help the Latinx community understand itself in relation to the US mainstream.

Many of his key contributions relate to Latinx identity. While the presence of Mexican Americans in the US is now evident to everyone, up through the 1960s there was little recognition of this hyphenated identity as having its own characteristics or any presence in the US. Someone could be a Mexican or an American, but the idea of a Mexican American had not received general recognition—at least, until Anaya began to write. Moreover, Latinos in general were not being presented in literature as having substantial, rich, and sometimes heroic lives.

Anaya was instrumental in helping to change this situation. Through his major works—including Bless Me, Ultima (1972), Heart of Aztlán (1976), Tortuga (1979 ), Alburquerque (1992), Rio Grande Fall (1996), Shaman Winter (1999), Billy the Kid and Other Plays (2011), and Poems from the Rio Grande (2015)—he invited mainstream culture in to see Latinx life for itself, including perspectives on how Latinos saw the world. He did this by highlighting his characters with dynamic, evolving worldviews, hopes, and dreams. Whereas prior to Anaya’s work there was a thin line separating being Mexican from being American, after Anaya that line blurred to become a cultural space and an identity in its own right. He assisted mainstream readers in seeing his world for themselves and appreciating characters and interactions previously unknown to them.

Anaya also promoted recognizing the beauty of Mexican American culture as a hybrid of various indigenous, European, and distinctly American strands. He believed that without an appreciation of the history of the Americas and the uniqueness of hybrid culture in this hemisphere, there could be no true appreciation of mestizo, mixed-race identity. And like Tomás Rivera, the other instigator of the Chicano Renaissance in the 1970s, he believed in the formative power of culture to shape identity and the very fabric of experience. Foregrounding the contributions of the Inca and the Maya, the ancient peoples of the new world—our version of the Greeks in Western civilization—he intended to make the backdrop of the Americas an obligatory frame for deciphering contemporary life in the US.

For me, there are also two personal dimensions of Anaya’s passing. In 1997 he and his wife, Patricia, became the adoptive grandparents of my children. Always remembering birthdays and graduations, the Anayas were wonderful family for over twenty years of Christmas and other holiday gatherings. This close relationship became an extended professional tie when I began publishing about Anaya’s work. And then in 2006, I became his editor/publisher and brought out his next seven works in the Chicana & Chicano Visions of the Américas book series at the University of Oklahoma Press.

But while I interacted with Rudolfo Anaya in a variety of professional ways, all of them fulfilling and productive, I will join many others in thinking of him as a teacher. He was only eleven years my senior, but I always thought of him as a wise elder who could be approached on any topic for deeper understanding. He was an accurate, insightful reader of people, and a Rudolfo eyebrow raised before a conversation’s end was a certain indicator of much more discussion to come. He was a direct communicator, and he seldom left anyone in doubt about where he stood on a topic.

A large circle of people loved Rudy Anaya, and we will miss him terribly. As a Latino and a writer, I can attest that Rudy changed the cultural landscape in ways that have been welcome and positive. I think that we will honor Rudy most directly if we continue to build on the values that he held dear: pride in Mexican American identity, recognition of hybrid Latinx culture, and honoring the hemispheric scope for understanding our culture. Thank you, Rudy, for sharing your wonderful life with so many friends.

University of Oklahoma