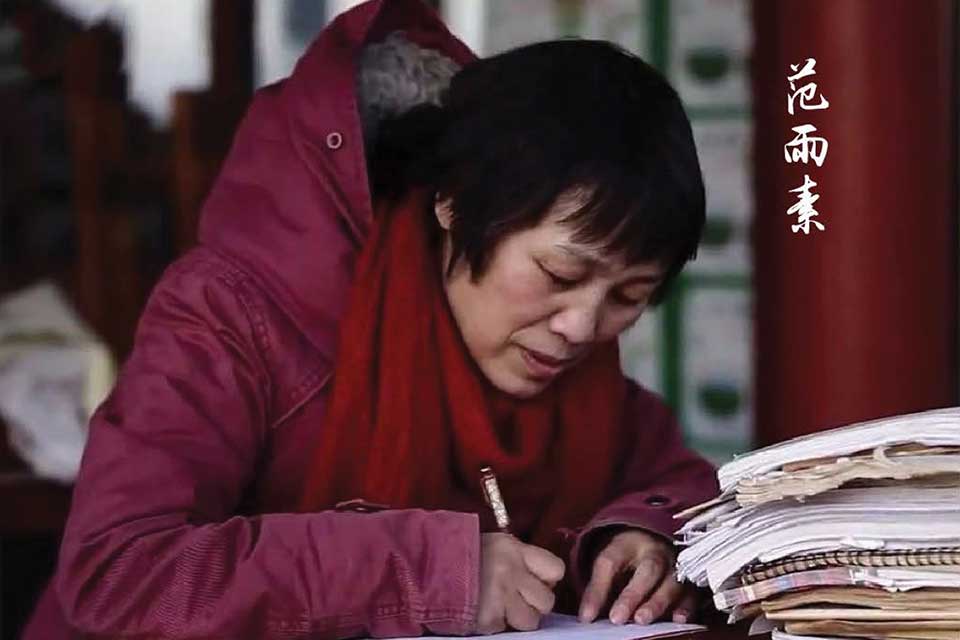

I Am Fan Yusu

Fan Yusu is a migrant worker from central China. She went to Beijing to work as a live-in nanny (baomu) and later joined the Picun Literature Group. On April 25, 2017, she published an autobiographical essay titled “I Am Fan Yusu” online, which immediately went viral and drew the attention of domestic and international media. The following is an excerpt (sections 5 and 6).

The Picun that I reside in is a very unique village. Every Chinese person knows that the villagers in the Beijing suburbs are all millionaires who own very expensive real estate. Most of those moneybags show off their wealth with their cars, watches, handbags, food, or clothing, but the Picuners disdain these ways. Instead, the people in Picun show off by raising an incredible number of dogs. One of my worker friends in Picun, Guo Fulai, came from Wuqiao in Hebei Province. He is a construction worker and resides in the workers’ shack in Picun. There is one villager in Picun who would lead his army of twelve dogs to patrol around the workers’ shacks every day, humiliating those migrant workers living in the shacks. In order to voice the concern of the migrant workers, Guo Fulai wrote a satirical essay, “The Dogs in Picun,” which was published in Beijing Literature.

My landlord is Picun’s former party secretary, equivalent to Picun’s ex-president. He is a self-fashioned statesman and looks down on the dog-army fanfare, so he only has two dogs. One is a Scottish shepherd and the other is a Tibetan mastiff. My landlord told me that Scottish shepherds are the most intelligent dogs in the world, and Tibetan mastiffs are the most valiant. The most intelligent dog and the most valiant dog have formed an alliance that is invincible. My daughters get to live in Picun’s ex-president’s mansion and enjoy the protection of the invincible security guards. My daughters and I all feel blessed.

After my older daughter learned how to read, I took many trips to the Panjiayuan flea market, the Hezhong thrift stores, and the junkyards, and bought her over a thousand pounds of books. Why did I buy so many books? There were two reasons: buying books by the pound was simply very cheap, and the books coming from the junkyards were so new that many had never been taken out of their plastic wrappings. A book that’s never been read is like a person who has never lived. It hurts my heart to look at them.

A book that’s never been read is like a person who has never lived.

I’d never written an essay before. Now whenever I have time, I write a novel with pen and paper, about the past and present of the people I know. I had little schooling and lack self-confidence. I write to satisfy myself. I’ve already come up with a title for this novel: Long-awaited Reunion. Its plots are not imagined, they are all real. Art comes from life, and everything about our present life is absurd. Every character in the novel can be verified. I always want to improve my writing for this self-entertainment project.

I attended the literature group of the “Workers’ Home” in Picun for one year. I had time to attend that year because I found a teaching job at a migrant workers’ school in Yingezhuang (a village adjacent to Picun) in order to take care of my younger daughter. The school pays very low salaries to its teachers, but they would hire anyone who applied for the job. Every month it paid me 1,600 yuan. I quit teaching after my younger daughter was old enough to go to school, return home, and buy food all on her own. I have been working as a live-in nanny earning 6,000 yuan every month, but I can only return home to see my younger daughter once a week and have never again attended the “Workers’ Home” meetings.

I have always thought of myself as an insensitive and weak person. I always read the newspaper without seeking a thorough understanding. If you strung together these several decades’ worth of news and looked closely, you would discover that before rural people could enter cities and work (around 1990), Chinese rural women had the highest suicide rate in the world. Their coping strategies were simply “cry, make a scene, and go hang oneself.” The newspaper would tell you that ever since they could work in the cities, rural women stopped committing suicide. But at the same time a bizarre new term came to be: “motherless villages.” The rural women no longer commit suicide; they run away from the villages. In 2000 I read a report, entitled “Wild Mandarin Ducks Are the Most Easily Separated,” about the fragile long-distance marriages of migrant workers. The rural women who ran away are also in such long-distance relationships.

The rural women no longer commit suicide; they run away from the villages.

There are many motherless children of migrant workers in the “urb>an villages” in Beijing. Perhaps because birds of a feather flock together, the two friends of my older daughter are both this kind of child. Their fate is indeed miserable.

My older daughter learned how to read the newspaper and fiction by following the subtitles on TV. Afterward, when my younger daughter no longer needed a babysitter, my older daughter, then fourteen years old, began working manual jobs. She endured the hardship and learned many skills. She turned twenty this year and already become a white-collar worker earning an annual salary of 90,000 yuan. In comparison, her friends Ding Jianping and Li Jingni are of the same age, but they don’t have relatives praying to heaven on their behalf, so they have both become screws in the world factory and terra-cotta soldiers on the assembly line, living their lives like string puppets.

*

I find that I am unable to trust people after many years of living as a migrant worker. I only keep up a bowing acquaintance with others, and sometimes even fear the greeting ceremony. I looked for my symptoms in psychology books in order to treat my illness. What I have is called “social phobia” or “civilization phobia”; and when it worsens, it turns into depression. It can only be treated by love. I recall my mother’s love for me. My mother is the only person who would always love me in this world. Every day I try my best to think about this, so my mental illness hasn’t gotten worse.

This year, my mother called and told me that our production team has acquired some land for the government to build a station for the high-speed railway between Zhengzhou and Wenzhou. My daughters and I, as well as my oldest brother’s family, are all registered residents in the village, where we have land. It is unfair that the village was only offering 22,000 yuan for each acquired mu of land. The production-team captain posted a notice asking every family to send a rights representative to lodge a complaint against the government, fighting for their own interests. My oldest brother has also left the village to work in the city, so only my mother is able to serve as a rights representative for my family.

Mother told me how she went with the rights troop to the town government, the county government, and, finally, the city government. Wherever they went, they were pushed and shoved about by the young staff whose job is to maintain >social stability. The sixty-year-old captain is the youngest in the rights troop, and he had four ribs broken by those young staff. Mother is already eighty-one years old, and the young staff, after all, have a conscience: they didn’t push her, they merely grabbed her by the arm and pulled her aside. As a result, my mother’s elbow was dislocated.

One mu of land was sold for 22,000 yuan. Land per capita was already quite meager in the village. How can the few villagers who are unable to work in the city survive? There is no person in power who cares to think about this; none of them cares to think about their souls. This is happening in every nook and cranny throughout China, and every Chinese person has accepted this fate.

It hurts me to think that my eighty-one-year-old mother is still fighting for the rights of her good-for-nothing children, rushing around in the frigid wind of the new year, yet all I can do is scribble out this piece of writing to express my remorse—what else can I do?

What can I do for my mother? Mother is a good and kind person. During my childhood, most of the villagers sought out reasons to bully the Junzhou immigrants living behind our house. They had been displaced by the Danjiangkou reservoir construction and moved to our village. The most famous historical figure from Junzhou was named Chen Shimei, who was chopped up by Judge Bao during the Song dynasty. Currently, Junzhou city is also submerged underwater. My mother, the strongwoman in the village, the person at the top of the pyramid, often prevented others from bullying the immigrants. >

My older daughter told me that the cultural communications company she works at gives each employee> one bottle of fruit juice every day. Since she is not a fan of soft drinks, each day after work she would hand the drink, with both of her hands, to the homeless old woman in front of her company, who makes a living by collecting scraps from waste bins.

Translation from the Chinese

Edited by Ping Zhu & Hui Faye Xiao

Read Hui Faye Xiao‘s essay on Chinese Domestic Workers’ Literary Writings from this same issue.